In New York in the 1960s, your first sight of gay pornography may well have been in public, looking in a sex shop window. If you were a gay kid, but closeted you would have reacted with pleasure, certainly, maybe even bliss – what Roland Barthes called jouissance. But there would also have been an inexplicable, almost sickening lust, and the fear of being seen looking. If you could bring yourself to buy one or two of these magazines, sealed in cellophane, or were allowed to buy them, your reaction – now perusing a magazine at home, in private – would perhaps then have included shock at discovering that the sex acts on display, or simply suggested, were at all possible; hope that you yourself would soon be performing them; anxiety that you yourself might be gay; shame about being gay; the fear, as well as nervous excitement, about what, beyond the sex, adult life would be like for you; and awe, if not also envy, of the almost impossible beauty of these men – all of them white men – shown naked on the page.

If you were also very shy, as Robert Mapplethorpe was (born in 1946, he was in the 1960s still a very young artist making jewellery, collages and assemblages inspired by Joseph Cornell, and not yet taking photographs inspired by Nadar, Stieglitz and Steichen), you wouldn’t merely have been afraid of being seen, you would have dreaded it. In private, you would have dreaded what life would be like. Alongside the hope that you yourself would soon have sex there would also, perhaps, have been hopelessness. You yourself, you may have felt, would never be able to respond – properly – to a come-on, or be able to seduce anyone else.

If you were raised Catholic, as Mapplethorpe was, it might also have seemed to you – as visions of Christ on the cross danced in your head – that the adult male body shown naked, or nude, rather, or at least the white male and rather Christ-like body shown nude, was a figure of transcendence. But the shame you felt about being gay would – I can only imagine, as I myself am not Catholic – have been an especially guilt-ridden shame. If you were into drugs already, as Mapplethorpe was, well, I’ve never done drugs either, so I can’t really imagine what else your feelings would have involved. But I imagine it would have been something else.

Mapplethorpe never put his actual reaction, public or private, into words of that sort. He put it, eventually, into photographs, and not just the homoerotic male nudes, which show both black men and white men, as well as the somewhat pornographic, sometimes seemingly painful and violent – or sadomasochistic – semi-nudes (those men are usually in leather). He put it into self-portraits, artist portraits, society portraits, celebrity portraits, figure studies and even still lifes – almost all of them done in black-and-white. And he expected, for some reason, or perhaps he just hoped, that other people, gay or not, shy or not, Catholic or not, druggy or not, would react to them as he did. Perhaps, then, the Mapplethorpe aesthetic should be said to have involved ‘defamiliarisation’ – ostranenie, as Viktor Shklovsky called it – on acid. Or maybe defamiliarisation on poppers. ‘Art exists that one may recover the sensation of life,’ Shklovsky didn’t quite say. ‘It exists to make one feel things, to make the cock cocky.’

‘The first time I went to 42nd Street and saw those pictures in cellophane,’ Mapplethorpe told an interviewer in 1981, ‘I was straight and didn’t even know that those male magazines existed. I was 16 and not even old enough to buy them. I’d look in the window at those pictures and I’d get a feeling in my stomach. I was in art school then and I thought, God, if you could get that feeling across in a piece of art … It was exciting but definitely forbidden.’ In another interview, a bit later:

I became obsessed with going into [the shops] and seeing what was inside these magazines. They were all sealed, which made them even sexier somehow, because you couldn’t get at them. A kid gets a certain kind of reaction, which of course once you’ve been exposed to everything you don’t get. I got that feeling in my stomach, it’s not a directly sexual one, it’s something more potent than that. I thought if I could somehow bring that element into art, if I could somehow retain that feeling, I would be doing something that was uniquely my own.

Mapplethorpe says something almost identical in Black White + Gray (2007), a documentary about the art curator and collector Sam Wagstaff, who in 1972 became Mapplethorpe’s lover for a time, and then his longtime mentor and extravagantly generous patron. Wagstaff called Mapplethorpe his ‘shy pornographer’, an allusion, perhaps, to a novel from 1945 – Memoirs of a Shy Pornographer – by Kenneth Patchen.

I can find no evidence, however, that anyone else – certainly not such virulent homophobes as Senator Jesse Helms or Reverend Donald Wildmon, who couldn’t consciously allow themselves to see Mapplethorpe’s images as anything other than outrageous pornography – reacted to the photographs in the way Mapplethorpe hoped they would, at least not back in the late 1970s through to the early 1990s, when, thanks to Wagstaff, Mapplethorpe first became famous and then, thanks to Helms and Wildmon, infamous. Nor can I find evidence that any critics back then – critics, that is, who were both supportive of Mapplethorpe and aware of things he’d said, like those words from 1981 – wondered if the reaction he was seeking to evoke, in all its complexity and contradiction, its pleasure, bliss, lust, fear, shock, hope, anxiety, shame, excitement, awe, envy, dread, hopelessness, sense of transcendence and guilt, was even possible. Arthur Danto, in Playing with the Edge (1995), is one such critic. Mapplethorpe, he wrote, ‘played with the edge that separates art and mere pornography mainly because he cherished the feeling the latter induced in him in those first powerful experiences with crude images’. He does not say precisely which feeling. Wendy Steiner, in The Scandal of Pleasure (1995), is another such critic; Richard Meyer, in Outlaw Representation (2002), is another.

In fact, some critics back then, supportive of Mapplethorpe but unaware of what he’d said, found nothing at all pornographic – or so they have claimed publicly – about the work. Roland Barthes, for instance, who in Camera Lucida (1980) writes of one self-portrait by Mapplethorpe:

This boy with his arm outstretched, his radiant smile, though his beauty is in no way classical or academic, and though he is half out of the photograph, shifted to the extreme left of the frame, incarnates a kind of blissful eroticism; the photograph leads me to distinguish the ‘heavy’ desire of pornography from the ‘light’ (good) desire of eroticism.

Compare that to remarks made by Wayne Koestenbaum in these pages: ‘It is because Mapplethorpe’s images are jerk-off grist that they should be of surpassing interest to serious students of the imagination.’* For Mapplethorpe, although Barthes didn’t know it, all such self-portraits would have signified – to viewers in the know – a fetish. ‘Though often published,’ the editors of The Archive write of one, ‘the discussions surrounding this self-portrait never recognise that Mapplethorpe posed himself with his armpit as the focal point to deliver a message.’ He ‘created a calling card to identify one of his personal kinks’.

Is the reaction Mapplethorpe experienced and sought to evoke – whether in private or in public – possible today? Now that all kinds of even more outrageous, even truly violent pornography – films more than photographs – are so readily available (and for free) on the internet. (You can even ‘friend’, on Facebook, today’s equivalent of the gay porn ‘stars’ whom Mapplethorpe would have befriended in reality, and then photographed.) And now that Mapplethorpe himself, having died from an Aids-related illness – as Wagstaff did too – in 1989 at the age of 42, can no longer be sensed quite so readily as the real, rather problematic, or at least puzzling, presence behind and subject matter of his photographs. The real erotic subject matter, I should say. (‘I am particularly disturbed,’ Jonathan Weinberg writes in his essay in The Archive, ‘by the way so much of the writing on Mapplethorpe sees his images of the male nude and his pictures of sex as merely projections of his own fantasies and pathologies.’) And also now that Mapplethorpe’s infamy is such a distant memory.

I ask the question because notwithstanding Koestenbaum’s comments, and not, I think, because of Barthes’s position in Camera Lucida, and not just because I don’t have a thing for leather, or armpits, I don’t now find (actually I don’t recall ever having found) any of Mapplethorpe’s photographs, even his so-called sex pictures, to be ‘jerk-off grist’. Nor is my reaction to his photographs anything like my reaction the first time I saw gay pornography. The photographs are far too self-consciously arty – and perfectly beautiful – for that, not to mention too self-consciously stagy and ritualistic. (And so, I think, his photographs are not what the critic Jennifer Doyle would call ‘difficult’ art. They do not suggest, among other things, defiance, instability or mess.) Their real subject matter, that is, now seems to be not Mapplethorpe himself, his eroticism or kinkiness, but their own aestheticism. As works of art, that is, these photographs are so clearly classically beautiful. The balance and symmetry in them – no matter who or what is being shown – is what strikes the viewer: the dramatic lighting; the obvious tension; the meticulous framing; the tendency towards minimalism or even abstraction.

This, for the most part, is how the essayists in these two books – along with their editors – also see the photographs. ‘They are less a documentation of sexual activity than a representation of it as a purified ideal, reduced to basic forms and geometries – the effects of studio lighting and deliberate composition,’ Ryan Linkof writes. ‘The men in the images often appear frozen in a moment of stasis, isolated and neatly contained within the frame, and subject to the constraints of the photographic studio.’ Mapplethorpe’s work, Jonathan Katz says, ‘seductively elicits a response of aesthetic pleasure from the encounter with images that might in other circumstances trigger discomfort or even disgust’. Perhaps, then, the Mapplethorpe aesthetic should also be said to have involved a sense – or the classical sense – of the sublime: beauty plus terror.

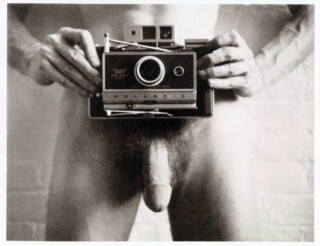

There is one interesting exception: Weinberg again, who, looking at one single photograph, a Polaroid he hasn’t seen before, taken of Mapplethorpe’s penis by someone else and blocked out when it was used for promotional purposes, experiences something like what both he and Mapplethorpe must have thought and felt on first viewing gay pornography:

Suddenly, amid the austere, almost clinical surroundings of the study room [at the Getty Research Center], I was given the gift of being able to see the [otherwise] hidden penis of this pretty young man. I have seen many pictures of Mapplethorpe without clothes – even a film clip of him having his nipple pierced, but this image, no matter how cropped, made me feel as if I had truly seen the artist exposed and vulnerable. This feeling of titillation and uneasiness that I was seeing something not for my eyes reverberates with the story [the 42nd Street story] that Mapplethorpe repeatedly claimed was central to his ambitions as an artist.

Weinberg now ‘became keenly aware how my searching through the collection for materials to elucidate Mapplethorpe’s art was akin to Mapplethorpe’s perusal of the magazine shop, itself a kind of archive or library’. Otherwise, though, and not so interestingly, Weinberg’s reactions to photographs by Mapplethorpe conform to those of the other essayists – and also to my own. ‘Aesthetic pleasure – that is, the sense of the beauty and rightness of the form of the photograph, or sometimes the physical attraction of the actual men who are performing the sexual acts – substitutes for the potential jouissance of the sexual encounter,’ he writes. Or, I should say, Weinberg’s reactions to the photographs conform in this way once he has undertaken numerous – and self-consciously voyeuristic – viewings of them. ‘Such looking is not exhausted by a single glance,’ he writes. ‘It demands repeated and highly charged viewing.’

What none of the essayists or editors recognise, though, and in this they are no different from any other Mapplethorpe critic I have read, is that he had a lot in common with Cornell even after he had stopped making assemblages. Patti Smith, who lived with Mapplethorpe when they were both ‘just kids’ – the title of her memoir, published in 2010 – and who was his lover and then friend, says in her essay in The Archive: ‘Robert combined idiosyncratic components and transformed them into a contained work. He saved beads, claws, religious medals, black net, stars and bits of geometry. And like Joseph Cornell’s boxes, which Robert had long emulated, his arrangements of such materials served as visual poems.’ Cornell was a devout Christian Scientist, a celibate heterosexual (and probable nympholept) and a self-declared Romantic, whereas Mapplethorpe was a lapsed Catholic, a promiscuous homosexual (and probable narcissist) and a classicist. But both artists were always extremely ambitious and professionally well connected. And both aimed – perhaps above all else – in their work to idealise (or as Smith suggests, to poeticise) the creatures, or sometimes just the things, that they adored: in Mapplethorpe’s case a bodybuilder, or a calla lily; in Cornell’s a ballerina, or a butterfly. Both aimed, in other words, to show us a kind of transcendence that they felt to be sexual as well as spiritual. It’s just that in Cornell’s case, the sexuality, if not the adoration, was meant by him to have been kept hidden. In Mapplethorpe’s case, of course, it comes through – or out – loud and clear, and also I think very proud.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.