Anselm Kiefer first came to public attention in London in A New Spirit in Painting, the exhibition held in 1981 at the Royal Academy. It’s fitting, then, that this should be the venue for the first full retrospective in Britain, curated by Kathleen Soriano (until 14 December). Kiefer has always divided critics, some taking fright at his heavy Germanic imagery, others describing the experience of his work in religious terms. It has lost none of its ability to provoke in either direction. Visitors circulate unusually slowly, silently contemplating the works. Looming at the top of the Academy stairs is a big sculpture, Language of the Birds (2013), a pile of large books made of lead sheets, interleaved with metal park chairs, surmounted by a giant pair of outspread wings, also of lead. Made from elements familiar from Kiefer’s work over the past forty years, the sculpture signals the epic journey that lies ahead.

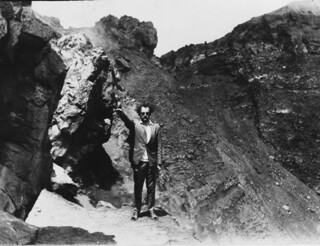

At the heart of Kiefer’s work is an idea and image of history. For the series of photographs entitled Occupations, which launched his career in 1969, he posed in different European locations dressed in military garb and performing a Nazi salute. The claim some have made that the photographs are evidence of fascist sympathies is bizarre – the satire is obvious. Although other German artists – Gerhard Richter and Markus Lüpertz, for example – had used military imagery, only Kiefer was reckless enough to portray himself as a Nazi. Kiefer was breaking a taboo about showing the recent past, but he was also saying something about the present – about the confrontation of generations that was then taking place in West Germany. Those who were too young to have taken an active part in the Third Reich (the ‘blessed’ generation in Helmut Kohl’s phrase), were confronted with a society still dominated by collaborators. The task was to hold a mirror up to West German society, to show what it had been, and to some extent what it still was.

In paintings and books made over the next few years Kiefer seemed to plunge further down into German history, into the constellations of art and culture that had become so problematically entangled with fascism. His art is in this sense a form of unravelling. Man in the Forest, for example, a painting from 1971, is one of the first statements of his fascination with the theme of the forest and trees central to the Nazi myth. In a picture recalling Caspar David Friedrich’s The Chasseur in the Forest, Kiefer paints himself in a white gown, holding a burning branch in a thick forest, the oil layered and dripping as if the work was itself the outcome of a pagan rite.

With Kiefer there is always a sense of meanings lurking just beneath the surface, of barely hidden taboos. Four paintings from 1973 on the theme of the Parsifal legend (three are included in this show) depict an attic space, in fact Kiefer’s studio at the time, the canvas dominated by the wood grain of the interior, done in charcoal on an oil ground. Inscribed on the canvas are the names of characters from Wagner’s opera and Gurnemanz’s line ‘Oh, wunden-wundervolles heiliger Speer!’ (‘Oh wounding, wondrous holy spear!’), which puts one in mind of Albert Speer. Also inscribed are the names of members of the Baader-Meinhof gang – Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin had finally been arrested shortly before Kiefer began the work. Half-buried in the wood grain effect (a Kiefer trademark), the combination of names suggests not only ‘difficult meaning’, but also the generational conflict which was to culminate in the events of the Deutscher Herbst (German Autumn) a few years later.

Kiefer is one of the few living artists who can work convincingly on a truly monumental scale, creating vast works that seem not merely to take up, but to activate the space around them. This is particularly true of his paintings based on fascist architecture. The vast canvas Ash Flower (1983-97) is more than seven and a half metres long, and almost four in height, and shows a large ruin of what had been a classical interior in plunging single-point perspective, clay, ash and earth forming the desiccated surface. An enormous dried sunflower is attached, inverted, in the centre of the canvas. Peter Schjeldahl saw an ‘energetic contradiction of the frontal and the recessive’ in these works, which he compares to the paintings of Jackson Pollock. He refers to the sense of being caught between diving into the image, drawn into the perspectival vortex, or remaining on the surface of the canvas, seeing it as a physical object rather than an imaginary space. For perspectival recession read historical imagination, and for scarred surfaces read the historical present in which Kiefer was living and working, a Germany consumed with the task of reconstruction and, in its national life, the work of constant redefinition. According to Andreas Huyssen, this oscillation between past and present becomes a dilemma for the viewer, caught between the feeling of being ‘had’ and falling for the monumental aesthetic beguilingly presented as ‘art’. Hold onto the surface, remain in the present, if you can.

The final painting in the architectural series, Sulamith (1983), is one of Kiefer’s best-known works, and possibly his greatest. It shows a low-ceilinged vaulted chamber, based on the Nazi architect Wilhelm Kreis’s 1939 memorial hall for German soldiers. The charred walls and glowering atmosphere of Kiefer’s version, and above all the inscribed ‘Sulamith’ show that far from being a Nazi Valhalla this is a Holocaust memorial. The ‘ashen-haired’ Sulamith and the ‘golden-haired’ Margarethe are from Paul Celan’s Todesfugue; the loss of Sulamith is a symbol of the Holocaust. Political reunification in 1990 restored the former east, but the real ‘other half’ of German history, the Jewish part, could never be restored.

Kiefer’s range of subject matter and references is epic. Since the 1980s overtly Germanic themes – the forest, the Nibelungen, the Third Reich – have been joined by Mesopotamian history, Egyptian and Greek mythology, the Old Norse Edda and the Kabbalah. A summary of these interests is captured by The Rhine, an installation of monumental woodcuts displayed on free-standing screens: Goethe, Dürer, fascist architecture, the poetry of Celan, all hovering above an image of the longest German river. It is a testament to Kiefer’s tact that, despite the grandiosity of these themes, his work never feels overblown. At the heart of the Royal Academy display is an installation, Ages of the World, a title loosely translated from the German Erdzeitalter. A lofty, tapering stack of discarded canvases, stretched and rolled, interleaved with old photographs, rubble, lead books and more large dried sunflowers gives off a faint odour of the dust and solvent of an artist’s studio. Two works on the wall, large photographs of the sculpture overpainted with words, annotate the stack in terms of the strata of geological eras. At first it seems to be a monument to art’s failure in the face of history, or an attempt to escape history. The critic John Russell saw an earlier form of the work, titled Twenty Years of Solitude (1971-91) as a ‘portrait of the artist as Atlas, bearing upon his shoulders a whole world in epitome’. But despite this the mood remains somehow light, as though a burden has been shifted, a knot unravelled.

This (relative) lightness of mood is one of the most striking qualities of Kiefer’s monumental works. These have taken the form of vast crumbling concrete towers, libraries of lead books – or the two enormous studio complexes he runs in France (descriptions of visits to these studios to interview the artist are a sub-genre of the Kiefer literature). The effect can be seen in the large canvas For Ingeborg Bachmann: The Sand from the Urns, 1998-2009 (even the date range is epic) which shows a large brick structure, perhaps a tomb, barely visible beneath a surface of acrylic and shellac (who knows what else might be lurking in there), the whole thing encrusted in a thick layer of sand. The title refers to the two poets whom Kiefer holds in greatest reverence; when Celan embarked on an ill-fated affair with Bachmann, he inscribed his poem ‘In Egypt’ in his collection The Sand from the Urns for her: ‘Thou shalt say to the strange woman’s eye: be the water!’ The surface of the painting recalls Joyce – ‘These heavy sands are language tide and wind have silted here’ – but at the same time his citation from Celan counters the heaviness of the lead books, the pyramids, the halls of fame, with a dash of mysticism to suggest that there is something to be read in those leaden tomes after all. His schoolbook-like script (which strongly recalls the lettering Kitaj used on his paintings) adds to the sense of more simple histories and truths, and also reveals something of Kiefer’s sense of humour, which he has sustained since the absurdist satire of the Occupations photographs. An endearing crankiness helps his work to survive the grandiosity of its subject matter.

As a retrospective the Royal Academy show is far from definitive. A weighting in favour of recent works, including two large diamond-encrusted lead-sheet ‘paintings’, and a room of seven new paintings, characterised by their rich gilded surfaces and grouped under the title Morgenthau, gives the impression of a mid-career show, organised in a commercial rather than a scholarly context (although the catalogue is highly informative and contains a fine essay by Christian Weikop on Kiefer’s use of tree and forest symbolism). It offers an opportunity to marvel, but not to get beneath the skin of Kiefer’s work, or to see him alongside other artists. His considerable debt to Joseph Beuys, at one time his teacher, is a case in point. The dried roses Beuys stuffed in a piano in 1969 are surely the origins of Kiefer’s sunflowers; and where Beuys used felt and fat as his signature materials, Kiefer uses lead (salvaged, we are told, from the roof of Cologne cathedral). The use of inscriptions, and the sense that an attempt is being made to create allegories of recent history also joins the two artists, although there are many differences too: Beuys was not a painter, for example; and Kiefer, since his Occupations photographs, is not known for performances. And in many respects Kiefer has gone beyond his former teacher in creating a body of work that captures the experience and memories of a German artist working in the wake of the Third Reich. But it isn’t his subject matter, or even its poetic transformation, that makes Kiefer’s work so beguiling, particularly when compared with that of artists such as Beuys or Georg Baselitz. It is something far more prosaic: the fascination of running one’s eyes over the intricate surfaces of his paintings, admiring the sense of design in his woodcuts, his skill in painting in watercolour, or ingenuity in recycling materials for sculpture – the pleasure of wondering how it was all done.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.