In ‘Confessions of an Old Jewish Painter’, the unfinished typescript for which was discovered among his papers after his death in 2007, R.B. Kitaj describes the origins of his bookish approach to painting. As a student at the Ruskin School of Drawing in the late 1950s, he attended lectures by the German art historian Edgar Wind, so popular that they were held at the Oxford Playhouse Theatre. The lectures taught him about the intellectualised world of floating images. ‘Wind led me to his master, [Aby] Warburg, who died semi-mad in 1929; and Warburg led me to his legacy and to his legatees – Panofsky, Saxl, Bing, Wittkower, Otto Pächt, the younger Gombrich and all the rest.’

It wasn’t only Warburg’s poetic method that inspired Kitaj. What also mattered to him was Jewish culture, as represented in the Warburg Library, evacuated to London in the late 1930s. The people who had enabled its move were the ‘stunning face of the Jewish diaspora in one of its grandest moments’. His neighbours in Dulwich, where he lived while continuing his studies at the Royal College of Art, included Fritz Saxl and Gertrude Bing (‘But you know so much about us!’ Bing said, when Kitaj showed up for tea). These early experiences convinced him that ‘Warburg was to art history what Einstein was to physics, Wittgenstein to philosophy, Freud to the study of the mind, Eisenstein to film, and so on: Jewish founding fathers of modernism.’ Warburg was the prophet of iconology, just as Bernard Berenson, another Jew, had been the prophet of connoisseurship.

What it might mean to be a Jewish artist (‘that arguable creature’, as he put it) became Kitaj’s central obsession, giving him his subject matter but also shaping his approach to image-making, and in particular to drawing. What stuck in the mind on visiting the Kitaj retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1994 was his extraordinary draughtsmanship: the charcoal drawings and pastels that seemed in their strangeness and sureness of touch to come from another world – they were certainly out of place in early 1990s London, awash with hip young conceptualists.

One of the most striking of Kitaj’s images, included in the current exhibition at Piano Nobile (until 26 January), is a large charcoal drawing on canvas from 1977 of his mother, Jeanne Brooks. She was a ‘tough old bird’, Kitaj recalled, the daughter of Russian-Jewish immigrants, who had raised him alone in Cleveland, Ohio, before marrying her second husband, Walter Kitaj. In the drawing, Brooks lifts her head from the letter she is reading, her attention caught by something beyond the frame. Her earring echoes the dowelling pivot of the deckchair – a neat pictorial device – but our attention lingers on the odd relation of body parts: her over-large hand and the odd shape of her head, with its slightly protuberant brow and guileless expression. The rich black tones and blurring effects seem photographic, but stranger than straight photography, as if the principle of photomontage had been applied to drawing itself.

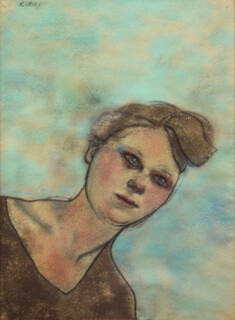

Kitaj’s bookishness wasn’t only a matter of literary references, which recur in his work; he also drew on the photographic reproductions that transformed art books during his lifetime, particularly those published by what he called the ‘old Jewish’ Phaidon Press. The pastel drawing Red Eyes, on display at Piano Nobile, shows a tearful woman jutting diagonally into the picture, as if looming over us. The pose is derived from a detail of a monk painted by Giotto in the Bardi Chapel of Santa Croce in Florence (reproduced in Cesare Gnudi’s monograph of 1959); Kitaj usually showed his model, Marynka, from less than monastic angles. Although Giotto provided the pose, the drawing bears more affinities with Degas, whose drawings, Kitaj once wrote, ‘are one of those artistic achievements by which I measure all art’. After seeing an exhibition of Degas’s pastel works in the mid-1970s he went to La Maison du Pastel in the Marais, bought some Henri Roché crayons ‘from two ancient sisters who may have served Degas’ and determined to ‘draw better than any Jew who ever lived, as a riposte to my anti-Dreyfusard master’. Degas was one of his favourite antisemites, Kitaj wrote; the others were Pound and Eliot.

Pastel, particularly the crumbly Roché sort, can be used in layers, like glazes of pigment, but also as a drawing medium, which perfectly suited Kitaj’s sensibility as a painter anchored in draughtsmanship. His return to drawing in the 1970s was largely due to his partner, the artist Sandra Fisher. ‘Why leave the game to your pal Hockney?’ she taunted him. Just as for Hockney – ‘the best natural draughtsman alive’ – drawing was always the starting point for Kitaj’s paintings, though the two couldn’t be more different in expression. Unlike Hockney, Kitaj was completely uninterested in new technology, quoting Ogden Nash that progress was a fine thing, but had gone on too long. When Hockney suggested that he get a fax machine, Kitaj answered that he would rather install gaslight.

For all this, Kitaj relied on photography and reproductions for his drawings and paintings – a good Warburgian, perhaps. In his drawings on canvas using the reddish-brown pigment known as caput mortuum, Kitaj comes closest to Walter Sickert as a painter of photographs. His images of baseball players, including Stanky and Berra at St Petersburg, from 1967, on show at Piano Nobile, are the equivalents of the music hall subjects beloved by Sickert. Kitaj’s portrait of Auden from 1968 is one of the best of these painted drawings. He visited him in California with Hockney, whose ink portrait from the same sitting gives more emphasis to Auden’s sagging face. (‘If that’s his face, imagine his scrotum,’ Hockney is said to have remarked.) Kitaj’s portrait seems made with more regard for Auden as a literary giant – one who had just dedicated his poem ‘The Truest Poetry is the Most Feigning’ to Edgar Wind. Kitaj borrowed a line from Auden’s ‘Letter to Lord Byron’ for the title of the Arts Council exhibition he selected in 1976 – The Human Clay – though it was Hockney’s love of the phrase that drew it first to Kitaj’s attention.

Kitaj discovered Walter Benjamin through reading an essay by Gershom Scholem, and more thoroughly in Hannah Arendt’s introduction to Illuminations. Montage and the disjunctures of photomontage are the structuring principles for the handful of paintings on which Kitaj’s reputation rests, many of which seem like drawings coaxed into colour. The same can be said for his greatest painting, If Not, Not (1975), a political-poetic landscape, displaying Eliot – with a hearing aid – underneath the gates of Auschwitz. (The picture is familiar to visitors to the British Library from the tapestry copy that hangs in the entrance hall.) Kitaj’s attempt at 20th-century history painting in these large works is somewhat compromised by their riddling, obscure meanings – but they don’t get in the way of his consummate drawing and unerring sense of colour and design.

In Marrano (The Secret Jew), a painting from 1976 showing a man in beret and swimming trunks talking on the telephone, forms are spread and flattened, the thin, scrubbed pigment giving a burned, dusty look (‘a sort of magma or “scorched earth”’, as John Ashbery put it). The body parts don’t quite hold together. Kitaj’s Marrano (the Spanish term for a Jew who converted to Catholicism to avoid persecution) has long, sexy legs, sitting oddly against all sense of the tragic, however skeletal his top half looks. The accent here is on the bizarre, the strangeness that Kitaj saw as essential to all good art: ‘No real artist would want to practise a normative art … the best art is strange.’ You might see Kitaj’s written ‘prefaces’, short commentaries often presented alongside his paintings, as an attempt to anchor this strangeness, to give it some kind of verbal structure. Without them, his paintings can appear like half an equation, wanting some kind of explanation, however convoluted. His drawings are less reliant on exegesis, and for that reason often more satisfying as works of art.

It is hard now to imagine why Kitaj’s ‘prefaces’ (‘not explanations’) were once so controversial, fodder for harsh criticism of his work. ‘The Wandering Jew, the T.S. Eliot of painting?’ Andrew Graham-Dixon wrote in the Independent of the 1994 retrospective. ‘Kitaj turns out, instead, to be the Wizard of Oz: a small man with a megaphone held to his lips.’ Kitaj’s reviews of his reviewers are always entertaining: ‘The art critic was the ghastly fundamentalist the Rev. Donald Judd,’ he writes in his autobiography, Confessions. He directed his greatest ire at those who wrote disapprovingly of his Tate show – the snobs and newspaper hacks blinded by their ‘loyalty to last week’s neo-Beuysian hunks of lard’. These critics, Kitaj wrote, want the artist to be like Clint Eastwood riding into town. ‘No one knows who he is or where he comes from. He just does his art real good, and says nothing and explains less.’

And yet his later works, which explain less, point to the limitations of his earlier work, particularly the riddling imagery and obscure allusions. The concise survey at Piano Nobile illustrates Kitaj’s reckoning with the convoluted, often introspective forms of modernist art and literature he admired. As he grew older, he wondered if he would have benefited more from devoting his twenties to Rembrandt rather than to the Cantos of Pound. ‘I yearn for a deflation,’ he wrote, ‘not of mystery or complexity, but of opacity.’

It is with his drawings that Kitaj best staged this return to a more transparent type of image. His late paintings are really drawings with oil paint: painting-drawing, as he termed it in a lecture given in Los Angeles in the last years of his life, illustrating his point with late Degas, Van Gogh, Cézanne’s Bathers, analytic Cubism (the paintings rather than collages) and the apotheosis of the painting-drawing style in Matisse’s work between 1910 and 1920. It’s a term that should have stuck. The best of his late work is in this style. Kabbalist and Shekhina combines a memory of Matisse’s The Violinist at the Window with something of Kitaj’s own: his pursuit of kabbalistic communion with Fisher, represented as Shekhina, ‘the female aspect of God according to Kabbala’. What really counts is the memory of Matisse, and the sense that only through the directness of drawing was Kitaj able to recapture the memory of his wife.

The painting-drawing style reached its conclusion, for Kitaj, in his ‘little pictures’ of faces and heads, made in the final two years of his life. Arendt is drawn with deft touches of colour, compressed into the centre of the small canvas, returned to the scene of the Eichmann trial; while Kitaj’s own features appear in the sorrowful guise of the Hunter of Gracchus, Kafka’s mythical figure who roams the world, unable to die, caught, as it were, in a state of eternal diaspora.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.