Rembrandt’s Artist in His Studio, c.1629, is a small picture with a blazing message. The viewpoint is that of one seated on the bare floor in the corner of an attic studio with crumbling plaster walls. On the right, in shadow, is the doorway. In the centre, with its back to us, is an enormous easel with a picture propped on it. On the left, barely half the height of the easel, stands the painter, brush and mahlstick in hand, dressed in his painting robe and hat. He is in shadow, but we can roughly make out his moon face as he stares at his picture. The light source, out of shot, is to the left of him and above. It falls almost entirely on the floorboards, turning them corn-coloured, and also on the left-hand edge of the painting on the easel, giving it a glittering vertical line. But because we can’t see where the light is coming from, the image switches round in our head: it is as if the painting is blazing out over the floor (but not onto the manikin-painter). So we are to understand: it is the art which illuminates, which gives the artist both his being and his significance, rather than the other way round.

Lucian Freud made the same point once with a brilliant aside. Any words which might come out of his mouth concerning his art, he remarked, are about as relevant to that art as the noise a tennis player produces when playing a shot. He wrote one article for Encounter at the very start of his career in 1954, and at the very end added a few sentences to it for Tatler in 2004. (His view of art had not changed in the fifty-year interval.) Otherwise he kept textual silence. He issued no manifestos and gave no press interviews until his final decade. All this through a period when artists took over the colour supplements, and the easel painter seemed vieux jeu compared to the collager, silk-screener, installer, conceptualist, video-maker, performer, neon-signer and stone-arranger. There was much art babble, and newcomers were expected to provide credos of fluent obscurity. Flaubert once said: ‘The more words there are on a gallery wall next to a picture, the worse the picture.’

Flaubert also said, in reply to a journalistic inquiry about his life, ‘I have no biography.’ The art is everything; its creator nothing. Freud, who used to read aloud to his girlfriends from Flaubert’s letters, and portrayed the writer Francis Wyndham with a battered but recognisable copy of the first volume of the Belknap edition in his fist, would have agreed. But having ‘no biography’ is impossible: the nearest you can get is to have no published biography in your own lifetime. Freud, more than any other artist of his stature, came as close to that as possible. In the 1980s, an unauthorised biographer started delving, only to find heavies at his door, advising him to desist. A decade later, Freud authorised a biography and co-operated on it, but when he read the typescript and realised what biography entailed, he paid the writer off. He lived furtively, moving between addresses, never filling in a form (and hence never voting), rarely giving out his telephone number. Those close to him knew that silence and secrecy were the price of knowing him.

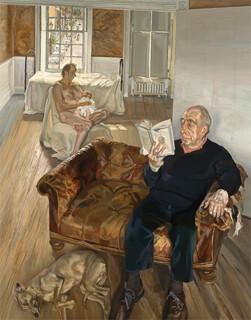

On Capri they show you the sheer cliff from which those who displeased the Emperor Tiberius were reportedly flung (though the Capresi, who call him by the softer name of Timberio, insist that the death toll was much exaggerated by muck-rakers like Suetonius). The court of Freud was similarly absolutist in its punishments: if you displeased him – by bad timekeeping, unprofessionalism, or disobedience to his will – you were tossed over the cliff. In the painting which shows Wyndham flaubertising in the foreground, the background originally held the figure of the model Jerry Hall breastfeeding her baby. She sat thus for several months, until one day she called in sick. When, a couple of days later, she was still unfit to pose, the enraged Freud painted over her face and inserted that of his long-time assistant David Dawson. But the baby had not caused offence, so was not painted out, with the result that a naked and strangely breasted Dawson is now seen feeding the child. Freud’s American dealer assumed the picture would be unsellable; it was bought by the first American client he showed it to.

Penelope Fitzgerald thought the world divided into ‘exterminators’ and ‘exterminatees’. Certainly it divides into controllers and controllees. A typical controllee is someone who is love-dependent; Freud was that once, and swore never to be so again. He was always a controller, and sometimes an exterminator. Martin Gayford and Geordie Greig’s accounts of Freud’s behaviour reminded me at times of two unlikely novelists: Kingsley Amis and Georges Simenon. When Amis’s second wife and fellow novelist, Elizabeth Jane Howard, saw him, at eleven o’clock on the morning he was due to lunch at Buckingham Palace, standing in the garden punishing an enormous whisky, she said, ‘Bunny, do you have to have a drink?’ He replied (and it was a reply that would have fitted a vast number of other exchanges): ‘Look, I’m Kingsley Amis, you see, and I can drink whenever I want.’ As for Simenon, he practised two things obsessively: his art and fucking (though his speed at writing contrasts with Freud’s slowness at painting). Simenon once winningly observed: ‘Maybe I am not completely crazy, but I am a psychopath.’ Freud confessed his ‘megalomania’ to Gayford, adding that there was a bit of his mind ‘that believes, just possibly, my things are the best by anyone, ever’. Amis, Simenon and Freud all had controlling, interfering mothers, which may or may not be relevant.

Freud always lived a high-low life: dukes and duchesses and royalty and posh girlfriends on one hand, gangsters and bookies on the other. The middle classes were generally scorned or ignored. He also had high-low manners: unfazed and relaxed in royal circles, a stickler for good manners from his children, but also indelibly rude and aggressive. He did whatever he liked, whenever he liked, and expected others to go along with it. His driving made Mr Toad look like a nervous learner. He would assault people without warning or, often, excuse. As a refugee child he would hit his English schoolfellows because he didn’t understand their language; as an octogenarian he was still getting into fistfights in supermarkets. He once assaulted Francis Bacon’s lover because the lover had beaten up Bacon, which was quite the wrong response: Bacon was furious because he was a masochist and liked being beaten up. Freud would write ‘poison postcards’, vilely offensive letters, and threaten to have people duffed up. When Anthony d’Offay closed a show of his two days early, an envelope of shit arrived through d’Offay’s letterbox.

In one version of the philosophy of the self, we all operate at some point on a line between the twin poles of episodicism and narrativism. The distinction is existential, not moral. Episodicists feel and see little connection between the different parts of their life, have a more fragmentary sense of self, and tend not to believe in the concept of free will. Narrativists feel and see constant connectivity, an enduring self, and acknowledge free will as the instrument which forges their self and their connectedness. Narrativists feel responsibility for their actions and guilt over their failures; episodicists think that one thing happens, and then another thing happens. Freud in his personal life was as pure an example of an episodicist as you are likely to get. He always acted on impulse; he describes himself as ‘egotistical … but … not in the least introspective’. Asked if he felt guilt about always being an absentee father to his large number of children, he replied, ‘None at all.’ When Freud’s son Ali, who was angered by his father’s massive absence, later apologised in case his own behaviour had caused his father anxiety, Freud replied: ‘That’s nice of you to say, but it doesn’t work like that. There is no such thing as free will – people just have to do what they have to do.’ He was a reader of Nietzsche, who thought us all ‘pieces of fate’. His episodicism applied to such varied matters as the weather (his favourite being Irish, which comes in many unpredictable forms each day) and grief (‘I hate mourning and all that kind of thing – I’ve never done it’). He thought the idea of an afterlife ‘utterly ghastly’ – perhaps because such a contrivance would prove narrativism. Not surprisingly, narrativists tend to find episodicists selfish and irresponsible; while episodicists tend to find narrativists boring and bourgeois. Happily (or confusingly), in most of us these tendencies overlap.

Though each new painting may be seen as a furiously concentrated episode, every artist can – and must – also be a narrativist, can and must see how one brushstroke is connected to the next, and how each has a consequence; how past is connected to present, and present to future, and how there is an unfolding story in any painting, which is largely the result of the application of free will. And also that, beyond this, there is a wider narrative: of self-instruction, of real or imagined progress, of an artistic career. Gayford’s Man with a Blue Scarf is a narrative of a single episode: his seven-month sitting for the picture of his title. Structured like a journal, with each entry amounting to a kind of brushstroke, it is one of the best books about art, and the making of art, that I have ever read. While Freud studies Gayford, Gayford studies Freud; as the portrait builds on the easel, so it does in the text. The actual process of posing Gayford wittily describes as ‘somewhere between transcendental meditation and a visit to the barber’s’. But he has fallen into the chair of the most demanding haircutter. Invited to make himself comfortable, he sits with his right leg crossed over his left, and the artistic process begins. After an hour or so, a break is called, there is already a charcoal outline of Gayford’s head on the canvas, and Freud flops down on one of the piles of rags that litter his studio. When Gayford returns to his chair he asks if he is allowed to cross left leg over right. Absolutely not, Freud replies, because it would subtly alter the angle of the head. And you would certainly have to take his word for that. Gayford, whose portrait was begun in November, also found himself lumbered with his heavy tweed jacket and scarf as the sittings dragged on into the following summer. Freud never used professional models, but demanded professional obedience from his amateurs. Everything was on his terms, even when the sitter was a fellow painter. David Hockney calculated that he sat for Freud for ‘more than a hundred hours over four months’; in reciprocation, Freud gave Hockney two afternoons.

Gayford provides an intense account of an intense process, of how art is made by a mixture of instinct and control, eye and brain, of nerves, doubt and constant correction. He describes Freud’s way of muttering and chuntering away as he works (‘Yes, perhaps – a bit’, ‘Quite!’, ‘No-o, I don’t think so’, ‘A bit more yellow’), his sighing and pausing, irritation at a mistake and triumphant waving of the brush at the conclusion of a successful stroke. In such constant self-commentary he resembles not so much that plosive tennis player but the cricketer Derek Randall (formerly of Nottinghamshire and England), who would chunter away to himself throughout an innings, constantly encouraging and rebuking himself between shots (and using his appropriately Freudian nickname of ‘Rags’). Gayford is also funny and honest about what a sitter goes through – the excitement, the shameful vanities (he worries about his ear hair) and the discomfort and boredom. A large side-reward is the pleasure and value (the more so for an art critic) of Freud’s high-quality table talk and easel talk. There is good gossip about his life and times, and Freud talks freely about his ambitions and procedures. Also about painters he admires (Titian, Rembrandt, Velásquez, Ingres, Matisse, Gwen John) and those he doesn’t: da Vinci (‘Someone should write a book about what a bad painter Leonardo da Vinci was’), Raphael and Picasso. He prefers Chardin to Vermeer, and dismisses Rossetti so violently as to induce pity. He is not just ‘the worst of the Pre-Raphaelites’ (Burne-Jones breathes a sigh of relief), but ‘the nearest painting can get to bad breath’.

Freud was always a painter of the Great Indoors. Even his horses are painted at home in their stables; and though he curated a great Constable show in Paris in 2003, the greenery he depicted himself lived either in pots or was visible from a studio window. His subject matter was ‘entirely autobiographical’. Verdi once said that ‘to copy the truth can be a good thing, but to invent the truth is better, much better.’ Freud didn’t invent, nor did he do allegory; he was never generalising or generic; he painted the here and now. He thought of himself as a biologist – just as he thought of his grandfather Sigmund as an eminent zoologist, rather than a psychoanalyst. He disliked ‘art that looks too much like art’, paintings which were suave, or which ‘rhymed’, or sought to flatter either the subject or the viewer, or displayed ‘false feeling’. He ‘never wanted beautiful colours’ in his work, and cultivated an ‘aggressive anti-sentimentality’. When there is more than one figure in a picture, each is separate, isolated: whether one is reading Flaubert and the other is breastfeeding, or whether both are naked on a bed together. There is only contiguity, never interaction. He greatly admired Chardin’s The Young Schoolmistress – which most would see as one of the tenderest (and most beautifully coloured) images of human interaction; Freud liked it mainly because the schoolmistress had the best-painted ear in the history of art. He admired ‘jokiness’ in a painter, finding it in Goya, Ingres and Courbet; though his own attempts at jokiness rarely come off. For all his intelligence, when Freud has an ‘idea’ in a painting, it is usually a bad and clunky one. The naked woman with two halves of a hard-boiled egg in the foreground (woman – womb – eggs; woman – breasts – nipples – yolks) is crass and juvenile. Painter and Model shows a clothed Celia Paul with her brush pointing at the model’s penis, while her naked right foot squeezes paint out of a tube on the floor. This makes the visual double entendres in James Bond movies look sophisticated.

Early on, he painted with a Memling-like precision, each hair and eyelash clearly delineated, with a light palette and a (comparatively) gentle eye. Then, switching from sable to hoghair, his brushwork grew broader, his tones dunner and greener, his canvases larger; some of his sitters grew larger too, culminating in the enormous Leigh Bowery and Sue Tilley the benefits supervisor (perhaps the most famous fat woman since Two-Ton Tessie O’Shea). Freud liked to emphasise his own incorrigibility, his instinct to do the opposite of what he was told to do; and several times in interviews he ascribed this major stylistic switch to being praised for the drawing which was the basis of his painting. So he decided to stop drawing and to paint more loosely. This explanation seems hardly credible, given his admiration for great draughtsmen like Ingres and Rembrandt. Further, no artist as serious as Freud, however contrarian he might be, would allow himself to be stylistically controlled by (even favourable) criticism. But the explanation draws attention away from the truer reason, which he also admitted: the influence of Francis Bacon. Freud lived his life instinctively, but painted with utter control; Bacon outdid him by seeming to paint instinctively, and at speed, with no preliminary drawing, occasionally finishing a picture in a morning. Some found Freud’s stylistic switch alarming, or worse that that: Kenneth Clark, an early admirer, wrote to Freud suggesting that he was deliberately suppressing what made his work remarkable. ‘I never saw him again,’ Freud tells Gayford. Another one off the Tiberian cliff.

This looser brushwork did not lead to any greater speed of work (though Freud was never to threaten the record 12 years Ingres took to paint Madame Moitessier). But it changed the way he portrayed flesh. From now on, as Gayford notes, even when he painted the young and smooth-skinned, he included in it the flesh’s vulnerability, ‘its potential to sag and wither’. Some thought he’d been doing that all along. Caroline Blackwood, writing about Freud’s portraits in the New York Review of Books in 1993, described them as ‘prophecies’ rather than ‘snapshots of the sitter as physically captured in a precise historical moment’. She added that his paintings of her had left her ‘dismayed’, while ‘others were mystified why he needed to paint a girl, who at that point still looked childish, as so distressingly old.’ Blackwood had much cause for resentment against her former husband (not least that he had slept with her teenage daughter), but this accusation seems misplaced. If we look at the Blackwood portraits now, it is more her anxiety and fragility that strike us, rather than any premature ageing. Gayford thinks Freud’s second style is all about mortality. In the self-portraits, he writes, Freud ‘seizes almost gleefully on signs of ageing and time’; and his ‘attitude to other sitters is in this way the same as his attitude to himself’. Perhaps; but I wonder if it isn’t more a question of style and brushwork than of a not very subtle message about mortality. This is the method Freud uses in his quest to intensify the sitter’s nature and essence, whether he is painting the naked young or the fully clothed octogenarian Queen of England. As for Freud’s many self-portraits, it is less their gleefully depicted decay that is striking than their self-celebration, their implicit stance of artist as hero. The worst is The Painter Surprised by a Naked Admirer, one of Freud’s ‘ideas’ pictures. It shows a naked model on a bare studio floor clinging to Freud’s ankle and thigh, as if to prevent him getting to his easel. Its intention may be jokey, but the result is both arch and vain. And perhaps it also doesn’t work because it is a rare attempt at showing interaction rather than contiguity.

Blackwood is right that her ex-husband’s portrait style is not flattering – nor was it intended to be. Even so, it comes as a shock, after a long looking at Freud’s paintings, to turn to the photographs of many of Freud’s sitters (and standers and liers) by Bruce Bernard and David Dawson in Freud at Work (2006). How sleek and erotic the human body really is, you think, and what a very nice colour too. Doesn’t the benefits supervisor look good, and isn’t our queen wonderful for her age? It’s remarkable how few wrinkles she’s got, considering. But then, photography has always been a flattering art – just as portrait-painting used to be. In the old days (and in some quarters still) there was an unwritten contract between painter and sitter, because the sitter was the paymaster. Nowadays the sitter only pays if he or she buys the picture; and in any case, Freud would ignore any such unwritten contract, even if he believed it existed.

Artists can be wrong about their own art: Gayford tells us that Freud’s aim was ‘to make his pictures as unalike as possible, as if they had been done by other artists’. This must have been some kind of necessary delusion, perhaps designed to ensure that his attention and ambition did not flag. But mostly, artists know more of what they are up to than we do. Freud’s aim was never to serve or copy nature, but to ‘intensify’ it until it had such force that it replaced the original. So a ‘good likeness’ is irrelevant to a ‘good picture’. His idea about portraiture, he once told Lawrence Gowing, ‘came from dissatisfaction with portraits that resembled people. I would wish my portraits to be of the people, not like them … As far as I am concerned, the paint is the person.’ He says to Gayford of his portrait: ‘You are here to help it’ – as if the sitter is a kind of useful idiot who helps the artist attain his larger aim.

This can get precious, or unnecessarily complicated. Presumably, what the painter wants is for the viewer, when confronted with a portrait of a sitter familiar to him or her, to say, ‘Yes, that’s him/her, only more so.’ The intensification will then have been achieved. But ‘likeness’ hasn’t, and can’t, be abandoned – after all, what is Freud’s intense scrutiny for, if not to see more clearly than others do? Would we ever react to a picture by saying: ‘Oh, that’s terrific – it looks nothing like him/her, in fact it looks like someone else, but funnily enough it’s like an intenser version of them.’ I think not. The question also gets muddled up with another: how far the portrait displays the sitter’s character, how far it acts as a moral likeness. Gayford rightly points out that we respond to a Van Eyck or a Titian or an ancient Egyptian statue ‘in ignorance of the sitter’s personality’. (Also in ignorance of whether or not it is a good ‘likeness’.) But our reading of that Van Eyck or Titian will not be personality-free: we do not see it merely as an arrangement of paint. Part of the encounter will be about working out what this painted imitation or substitution tells us about the long-dead original. When we look at a very great portrait – say, Ingres’s Portrait de Monsieur Bertin – we take its likeness for granted and (leaving aside our purely aesthetic musings) respond as if Monsieur Bertin were alive and breathing in front of us. In that sense, the paint is the person.

Gayford’s book is about an artist who also happened to be a man; Greig’s book is about a man who also happened to be an artist. Greig’s Wikipedia entry reminds us that ‘members of his father’s family have been royal courtiers for three generations’. Having edited Tatler and the Evening Standard, he is now, as editor of the Mail on Sunday, at the court of Rothermere. But more important to him, I would guess, were his years at the much more exclusive court of Freud. He spent many patient years applying for membership – collecting the friendships of other artists on his way to the main prize – before playing a cunning trick which gained him entry. He served at the court of Freud for the last ten years of the painter’s life, and, as he tells us, gained Freud’s ‘confidence and trust’. He did so to the extent that the back-flap photo of Breakfast with Lucian shows the painter halfway towards smiling – a rare achievement, since Freud had long perfected the granitic scowl he put on whenever a lens was raised in his direction.

Greig’s book is more substantial than it first appears – not just breakfast, but coffee and a light lunch too. When dinner – the full biography – arrives, its author will have reason to be grateful to Greig, who gained access to Freud’s early (and by now nonagenarian) girlfriends, to sitters, lovers, children and others who felt released into testimony by Freud’s death. Whether Freud himself would have felt his ‘confidence and trust’ had been misplaced is another matter. Greig’s book will certainly do Freud’s personal reputation harm. But it will also, I think, harm the way we look at some of his paintings, and perhaps harm the paintings themselves – at least until a different generation of viewers comes along.

At one point, Greig suggests (quite plausibly, to my mind) that Freud’s nudes might be related to those of Stanley Spencer; but Freud slaps him down, swatting at ‘Spencer’s sentimentality and inability to observe’. Had I been in Greig’s position, I might have offered Egon Schiele as a Viennese ancestor, for the gynaecological poses, the loose brushwork and the colouring (see, for instance, Self-Portrait with Raised Bare Shoulder which advertises the current show at the National Gallery). But I would have been slapped down in my turn: Freud regarded Klimt and Schiele as shilling shockers who were full of false feeling. I doubt many would accuse Freud of false feeling, or question the sincerity of his constant reassertion of the artist’s role as truth-teller. But there is more to it than this. As Amis put it: ‘Should poets bicycle-pump the human heart/Or squash it flat?’ Neither, one presumes, is the answer. The accusation against Freud would be that he is a heart-squasher, and nowhere more than in the female nudes which are the most contentious part of his output. They are proudly, truth-tellingly vulvic, literally in your face. His women lie splayed for inspection: Celia Paul, self-admittedly ‘a very, very self-conscious young woman’, found sitting for Freud felt ‘quite clinical, almost as though I was on a surgical bed’. Freud’s men, on the whole, keep their clothes on, and lead with their faces; Freud’s women, on the whole, (are made to) take their clothes off, and lead with their pudenda. His animals, which are allowed to keep their genitalia hidden, come out best of all – but then Freud did say he had ‘a connection to horses, all animals, almost beyond humans’.

There are two questions here. The first is technical, or physiological. There are many differences between people’s genitalia, but these differences are not expressive; they lead nowhere. That is why portraitists usually give more attention to the face, which is expressive, and does lead somewhere – to a sense of the person’s presence, and essence, even if it is a changeable essence. The second question is interpretative, and here autobiography, if it is not kept out, may percolate and stain. There is the male gaze in art; and then, beyond that, there is the Freudian gaze. His pictures of naked women are not in the least pornographic; nor are they even erotic. It would be a very disturbed schoolboy who successfully masturbated to a book of Freud nudes. They make Courbet’s The Origin of the World look suave. The question is the way in which they are autobiographical – given that all Freud’s work is – and here biography comes in.

We have known for many years, anecdotally, about Freud and women. That there were many of them; that he married twice; that his children were literally countless: he acknowledged 14, but may have had twice that number (he regarded any form of birth control as ‘terribly squalid’). On the whole, his women were posh; and, on the whole, teenagers when he met them. He was always a star – compelling, mysterious, famous, intense, vital. One girlfriend told Greig: ‘He was like life itself.’ Another said: ‘When he was not there it was as if the light got dim. In the same way, he made everyone who was with him feel more illuminated and somehow more alive and interesting.’ So far, perhaps, so good: the dangerously magnetic artist, into whose forcefield women are drawn, is a centuries-old trope. And there are even moments when Freud’s insistence on living life entirely on his own terms, with others fitting in accordingly, has its comic side. Here is a story which clearly means something to him, as he tells it to both Gayford and Greig with little variation:

For example, I like spinach served without oil or butter. Even so, I can imagine that if a woman I was in love with cooked spinach with oil, I would like it like that. I would also enjoy the slight heroism of liking it although I didn’t usually enjoy it served in that way.

If this was Freud’s idea of the heroic compromise a man makes when in love with a woman, it’s not surprising that London’s society hostesses did not consider him son-in-law material.

But Freud, who never put any limit on things, was more than just a charming womaniser. He was priapic, no sooner acquiring a woman than he was after another, while expecting the first to remain available. Blackwood, his second wife, found him ‘too dark, controlling and incorrigibly unfaithful’ – not that he acknowledged ‘fidelity’ as a concept in the first place. If this was hurtful, tough; the women could just get on with it. He was also sexually sadistic: two of his ex-girlfriends separately describe him twisting and hitting their breasts. But Greig’s most destructive witness for the prosecution is Victor Chandler, a public-school-educated bookie, thereby folding into one person Freud’s beloved high-low divide. He ‘adored’ Freud, but also tells the two worst stories about him. In the first, he and Freud – who is already drunk – went for dinner at the River Café. In front of them as they arrived were two North London Jewish couples. ‘Lucian could be terribly anti-Semitic,’ Chandler recalled, ‘which in itself was strange.’ He took exception to the women’s scent and shouted at them: ‘I hate perfume. Women should smell of one thing: cunt. In fact, they should invent a perfume called cunt.’

On another occasion, Freud and Chandler talked about women:

The conversation we had about that was that he needed sex to stay alive. It was his attitude to living, to need the release. I think he needed to dominate women in certain ways. He talked about everything. One night we had a long conversation about anal sex. He said unless you’ve had anal sex with a girl she hasn’t really submitted to you.

So what’s this? Just a bit of tittle-tattle, as if from the pages of the Mail on Sunday, leaked by some Crawfie of the atelier, designed to damage the reputation of a great artist? More than that, I think. If you know these two stories, you can’t unknow them, and they seem to change – or, for some, confirm – the way the female nudes are to be read. Some men, and many women, are, and always have been, made uneasy, indeed queasy, by them. They seem cold and ruthless, paintings more of flesh than of women. And when the eye moves from the splayed limbs to the face, what expressions do Freud’s women have? Even in the early, pre-hoghair portraits, the women seem anxious; later, they seemed at best inert and passive, at worst fraught and panicked. It is hard not to ask oneself: is this the face and body of a woman who has first been buggered into submission and then painted into submission? Asked why he disliked Raphael so much, Freud said that while he had done some marvellous things, ‘I think it’s his personality I hate.’

It is sometimes said of compulsive womanisers that they get off with women because they can’t get on with them. (I first came across this crack in a biography of the womanising Ian Fleming, who knew and cordially loathed Freud – who loathed him back.) François Mauriac, in his great novel of literary envy, Ce qui était perdu, puts it more subtly and tellingly: ‘The more women a man knows, the more rudimentary becomes the idea he forms of women in general.’ This was written in 1930, but is not irrelevant today. Though Freud painted very slowly, he painted all day and night, and ended up with a large corpus. Inevitably, he repeated himself, never more so than in the way he posed women. Though he usually paid no heed to his fan mail, he one day received a letter from a (black) woman solicitor asking why he had never painted any black people. And so he answered the letter, took up the challenge and painted her. No prizes for guessing the pose: naked, thighs open for our inspection, contorted head in the distance. It is a feeble picture. He called it Naked Solicitor.

Biography infects other pictures as well, or rather, adjusts our previous reading of them. I had always imagined, for instance, that the paintings of Freud’s aged mother in her paisley dress were gentle, tender works, similar in spirit to those Hockney painted of his aged parents. Biography corrects this interpretation. From an early age, Freud found his mother’s interest in him repellent (she would do dreadful things like bring him food when he was poor), and throughout his life he kept her at a distance. When his father died, she took an overdose; she had her stomach pumped, but major damage had already been done, and she was reduced to a shell of herself. Only then – when, as you might say, life had buggered her into submission – did he begin to paint her. And as he put it, she had become ‘a good model’ because she had stopped being interested in him. Freud’s cousin Carola Zentner found it ‘terribly morbid’ that he was ‘painting somebody who is no longer the person they were … because basically she was still alive physically but she wasn’t really alive any longer mentally.’ Does this matter? Artists are ruthless, they take their subject matter where they find it, and so on. I think that in this context it does matter, because these pictures present themselves as loving portraits of dear old Mum and therefore exemplify what Freud abhorred: false feeling.

Perhaps, in time, all this will cease to matter. Art tends, sooner or later, to float free of biography. What one generation finds harsh, squalid, unartistic, cold, the next finds a truthful, even beautiful, vision of life and the way it should be represented – or rather, intensified. Two or three generations ago, Stanley Spencer’s nudes shocked many. This little man posing himself naked beside voluminous women – indeed, wives – whose breasts obeyed the law of gravity. Now such pictures seem, yes, gentle, tender works, and a true depiction of love and lust’s playfulness. Will Freud come to seem the greatest portraitist of the 20th century? Will his nudes seem to future generations as Spencer’s do to us now? Or will Kenneth Clark’s regret at Freud’s early change of style appear vindicated? For myself, I think his tiny portrait of Francis Bacon greater than his monumental studies of Leigh Bowery. I also wish he had painted more sinks, and more pot plants, and more leaves, and more trees. More waste ground, more streets. Artists are what they are, what they can and must be. Even so, I wish he’d got out a bit more.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.