‘Rome completely bowled me over!’ Hitler declared on returning to Germany after his 1938 state visit to Italy. Mussolini had laid on a grand night-time tour that climaxed in a visit to the Colosseum, which – according to Christopher Woodward in his excellent In Ruins – ‘was lit from inside by red lamps so that, as if ablaze, it cast a bloody glow on to the grass and the ruddy brick ruins on the surrounding slopes.’* Descanting to Albert Speer, his pet pseudo-classical architect, Hitler explained that ‘ultimately, all that remained to remind men of the great epochs of history was their monumental architecture … What then remained of the emperors of the Roman Empire? What would give evidence of them today, if not their buildings?’

I often think of Hitler and his ‘Theorie vom Ruinwert’ – that only stone and brick should be used in Nazi buildings – when I gaze on the four great towers of Battersea Power Station. True, they are cast from ferroconcrete, the perishable material the Theorie sought to proscribe; and the underlying structure of the power station is welded from steel girders that would have been just as unacceptable to Hitler, but I feel the huge expanse of brickwork that clads the grand foursquare hulk would surely gladden his hypertrophying heart, as would the prodigious quantities of stone that line the stairwells leading up to its marble-lined control room. What he would make of the hundred-foot-long control desk, finished in enough walnut burl to furnish the dashboards of a thousand Jaguars, I have no idea, but overall I think the spectacle of Battersea, now on the brink of its fourth decade of ruination, would please him.

Woodward observes that Hitler – when it came to ruins at least – was a glass half full kind of guy. To him, the Colosseum’s sheer endurance made it a worthy monument to imperial ambition, one he wished to emulate with buildings that would also last a thousand years – although presumably he hoped they’d survive in better nick. Of course, by the standards of Rome and Luxor’s stonework – let alone Çatalhöyük’s – the Battersea brick pile is absurdly youthful. Still, I’d like to propose a sort of ruination coefficient based on variables of age, size and location, by which measure Battersea would rank alongside these far more ancient structures: the defunct power station, while only fully commissioned in 1955, is absolutely fucking huge (given a big enough counterweight you could lower St Paul’s into its now roofless turbine hall), and it’s also slap-bang in the middle of London.

From the roof level, which I visited the other day with its current developer, Rob Tincknell of the Battersea Power Station Development Company, the city heaves away on all sides in a modest swell of glass and masonry that stretches to horizons bounded by Battersea’s only real rivals: the escarpment to the north that supports the suburbs of Harrow, Hampstead and Highgate, and the one to the south where Wimbledon, Upper Norwood and Crystal Palace recline. Even with the new logo buildings – the Shard, the Gherkin, the Quill et al – spearing London’s lowering skies, Battersea remains unrivalled when it comes to that most banalised form of contemporary status: the ‘iconic’. Certainly Battersea’s iconic status was uppermost in Tincknell’s mind as he led me, together with his head of communications, Alison Dykes, through freshly landscaped grounds – hardwood decking, raised flowerbeds, gravel pathways – towards the sales suite, pointing out on the way a scale model of the power station about the size of the average family home. ‘Isn’t it fantastic,’ he enthused, ‘it’s the one they used for the Olympics’ closing ceremony, one of only seven iconic buildings that Danny Boyle chose.’

Inside the suite I took my squishy seat at an opulent lozenge of a table, Alison settled herself a few places off, Tincknell launched straight into his PowerPoint spiel – just as if I were some important oligarch or Chinese millionaire intent on investing. He told me his previous developments included such exercises in ‘place making’ as Portsmouth’s Gunwharf Quays, which gave me pause for thought, because the Quays is a completely generic example of the glass’n’steel mixed retail/residential/ commercial development, distinguishable only by the ghastly Spinnaker Tower, a signature eyesore of bellying white spars that makes Anish Kapoor’s absurd Olympics evisceration, the ArcelorMittal Orbit, look positively subtle. Oh well, no matter, because unlike the poor blitzed Pompey docks, or Stratford marshes, the power station has oodles of authenticity to spare. Or, as Tincknell put it: ‘Battersea has iconic authenticity, industrial heritage oozes from every brick.’ He went on to explain that the power station presented an ‘iconic image on London’s skyline’, and that this was why ‘iconic brands’ – such as Red Bull, the Batman movie franchise and, gulp, the Conservative Party (Cameron launched his 2010 election manifesto in its brick gulch) – chose to be associated with it.

I suppose I should have let Tincknell rattle on like this – he seemed happy enough. But the problem is that Battersea power station and I have form: I live less than a mile away, and its upside-down table leg chimneys have dominated my immediate skyline for almost twenty years: I clock them when I walk the dog in the local park, or if I go to the post office on the Wandsworth Road. On my way into town over Vauxhall Bridge I see them looming over the Thames littoral, while when I cycle home, late at night, across Chelsea Bridge, the sight of a late train emerging from the silhouette of the power station to head over the railway bridge towards Victoria always summons De Chirico’s canvases to my mind’s eye: the juxtaposition of colonnades, trains and arbitrary hunks – human musculature or masonry – evokes urban alienation by perspectival overdetermination. Anything fundamental happening to the power station – which has been slowly mouldering away through my entire adult life – will be the architectural equivalent of a ‘domestic’.

But again, to be fair to Tincknell, he’s not the only one who’s convinced of Battersea’s iconic status; he told me that 14,000 people had turned up for the public consultation meeting to consider his development plan – for any less emotive building numbers would have been paltry. Indeed, so many local people felt they had something to contribute that the meeting was held in the power station itself: a nice circularity, as if Battersea had been built solely as a venue for consideration of its own renovation. Still, I probably shouldn’t have chimed up with ‘Iconic of what, exactly, Rob?’ because Tincknell, dropped out of his script, was so flummoxed that after thirty seconds or so I had to rescue him: ‘You mean iconic of Britain’s great industrial past, don’t you?’ A pabulum he seized on, and which allowed him to continue spieling; at one point he got a slide up on the PowerPoint that juxtaposed equally vacuous ascriptions – Authentic/Exclusive, Industrial/Inclusive, Ours/But-It’s-Yours – and then told me that the great thing about the Battersea development would be its dissolution of these vaporous alternatives. The brand (he used the term shamelessly) would be both safe and exciting, both exclusive and – yes – inclusive. Rob is much preoccupied by what makes ‘a great place’, but worryingly – considering he aims to make Battersea an autonomous ‘city centre’ with its own arts scene – he doesn’t think the Barbican qualifies.

His own wish list when it comes to cultural capital seems oddly abbreviated. He told me he’s asked the Theatre 503 Company to consider moving to the renovated power station from their current venue above a pub up the road called the Latchmere, and referred a little gnomically to something that might be done with the Royal College of Art. There was also talk of the Chelsea Fringe Festival, and later, when he was driving me round the site in his big boxy black Range Rover, he showed me the pop-up park he’s had erected in which pride of place is given to the boat in which Ben Fogle rowed the Atlantic. A pub theatre company and a TV adventurer’s rowboat seem more Bilbo Baggins than Bilbao.

I don’t say any of this to be mean to Rob Tincknell; in fact, I liked him from the onset, and liked him still more when we got away from the PowerPoint icons of the iconic power station and began scaling the real thing. There was no gainsaying his enthusiasm for the building, and while his plan to create an internal sixty-metre atrium – so that those inside will look up at the chimneys soaring priapically over their heads – seems either nutty or embarrassing, there’s no disputing that it’s the sort of masonry magniloquence the global rentier elite revel in. Because, saving Rob’s green and tender egalitarian feelings, there’s absolutely no question that the new Battersea is all about catering to these folk – if not in person, then in the persons of those they buy and let to. Rob may speak of river walkways and thoroughfares running between the new blocks (all of which are to be named, touchingly, after ex-power station workers), but even on the tiny scale afforded by the model in the sales centre, the development screams Gated! CCTV! Security! And Rob himself let the cat out of the Gucci bag when he conceded, gesturing to the Chelsea side of the river: ‘Let’s face it, most people will be entering and exiting the site in that direction.’

The BPSDC have had the already meagre GLA requirement for so-called ‘affordable housing’ reduced in their case because they’ve chipped in a few million quid towards the new Northern Line extension that will connect Nine Elms and Battersea to Vauxhall. But really the need for this link lies almost exclusively with the tenants of all the developments that are underway between Vauxhall and Chelsea Bridges on the south side of the river – developments that exist in symbiosis with the great dark starship of the new US embassy, which is scheduled to touch down, by 2017 at the latest, on a carceral moated island scooped out on the site of the former fruit and veg market. I say the requirement for the tube link lies with the tenants, but really I mean all the low-paid domestic servants and retail servitors, who, unable to afford to live anywhere near central London, will have to be entrained daily from their bantustans in the deep south or the uttermost east, so they’re on hand to scrub the toilet bowls of the rich, raise their children and slice them their carpaccio.

The development at Battersea represents the final freeze-drying of what was once the most industrialised and forsaken of London’s liquid landscapes. The site of Battersea Park was once a swamp, and a notorious shambles or knackers’ yard operated where the power station now rots. Now, apart from small pockets of social housing too crap to be worth privatising or pseudo-mutualising, the centre of the city is mostly cleansed of anyone without a substantial income, capital or both. As with Lower Manhattan since the time of Mayor Giuliani – and there has been an acceleration under Bloomberg – London, if Tincknell and his kind are anything to go by, will become a safer, cleaner and fundamentally duller city. Those who view themselves as belonging to the ‘progressive’ left despair of people – I’m one – who regard the city’s genius as being the sum of its disparate, otiose, non-functioning and outright redundant parts. This is seen as a sort of urbanist nostalgie de la boue, a terrible indulgence by the likes of me who can head home and scrape the river mud from our boots with an authentic – or possibly even iconic – boot scraper that we picked up from an architectural salvage store.

But I say: this is pernicious nonsense. London is one of the least planned of major Western cities, and the current developments – Battersea included – are no exception. Of course I knew full well that when Tincknell described the power station as ‘iconic’ he meant no more than ‘highly recognisable’. His reverence for the building’s notorious fabric was clear when, up in the control room, he pointed out the thick glass-brick light fitments and said he’d been in touch with the original manufacturers so that they could be duplicated exactly. He also mused on what to do about the control room itself, saying that a restaurant would be too exclusive, and that he wanted the people of London to be able to enjoy its Art Deco delights: the brass-tooled switching equipment linked to obsolete substations and labelled in Bakelite, the panoramic view down into the yawning cavern of the old turbine hall. Yet reverence of this sort is simply Baudrillard’s ‘museumification’ writ very large indeed, and once they’ve done rebuilding the power station all that will be left of it is its iconic – in the Tincknell sense – status. It will be simply a larger-scale model of the one Tincknell bought from Danny Boyle’s stage show.

Yes, the power station will remain, surrounded by curvy residential blocks worming their way through the Great Wen’s mulch; and up on their winter garden balconies (fully glassed-in for year-round decontaminated use) its new masters and mistresses will gaze on it as if it were a huge skeuomorph, evoking a luxurious former age when London was a more homogeneous city with curious aspirations towards municipal socialism, which included the idea that the generation of power was a social concern and electricity a common good. Because this, of course, is what Battersea power station is really an icon of: that strange era, between the 1920s and the 1950s, when such a consensus prevailed. The very style of Battersea power station – part Dudokian soft modernism, part red-brick Metroland high on pituitary gland – reinforces this idea of gemütlich monumentalism; as a building, it’s the lineal descendant of Mr Wemmick’s castle. That the power station should have been designed, in part, by Giles Gilbert Scott reinforces its ‘iconic’ character, given that Scott was also responsible for so many other London memorabilia.

On our tour, Tincknell and I discussed the vexed question of the renovation work itself. Since 1983, when the power station finally ceased generating (it hadn’t been cranking out much current since the Clean Air Act was passed), numerous consortia have had a go, but the costs are phenomenal. Since it’s Grade II* listed by English Heritage, every bit of perished mortar, each chipped brick and rusted girder must be replaced as it was, and if not with exactly the same materials then with ones that are visually indistinguishable. As a result of this, the power station has had an amusing propensity to snaffle up wannabe developers for breakfast – then spit out their bones. I last visited Battersea a decade ago in the company of the Park Group’s PR man; these Hong Kong-based contenders had plans every bit as grand as Tincknell and his Malaysian backers, but as we strolled about the mighty ruin their man conceded that since the sulphurous coal smoke had been ‘scrubbed’, or cleaned, by being filtered through railway sleepers piled up inside the chimneys the difficulties were considerable. Tincknell didn’t flannel it, admitting that all four chimneys were going to be demolished and rebuilt. Together with all the other make and mend of brickwork and steel, the renovated power station will, indeed, be a simulacrum of its former self.

After leaving Tincknell to get on with what he describes as the culmination of his place-making career – he will be nearing retirement when the work is finally completed – I walked past Cringle Dock, the deliriously authentic waste treatment centre next to the power station site, then took a path that leads to the riverside. Here, in the lea of the new curvilinear blocks that are sprouting up with mushroom alacrity, there’s a water gypsies’ encampment: lots of narrow boats, a couple of old Thames barges, a rusty old freighter with an entire lawn growing on its deck, and a strange houseboat in grey metal that was designed by Finnish architectural students and then sailed here across the Baltic and the North Sea. (I know this because I was so taken by its oddity that a few years ago I almost rented the gaff.) In these few short yards I had travelled from the confection of place to a genuine location, and the awesome weight of the power station’s bowdlerisation lifted from my shoulders. Needless to say, the residents of Tideway Village are being denied access by the developers of this stretch of the riverside, St James, and will probably soon be forced from their mooring.

I had felt confident, before meeting Tincknell, that he’d turn out to be just another snack for the avid old hulk, but on examining the algorithm that underpins the BPSDC’s plan I’m forced to the conclusion that he might just pull it off. Sales of the as yet unbuilt flats have already topped £660m: more than the £400m the Malaysians paid for the site when they snapped it up, together with Tincknell and his plan, from the previous developers, an Irish consortium that had gone bust. Phenomenal sums will be needed to re-create the icon itself, but the apartment blocks, and the copious retail and office space, will supply the necessary leverage – so long, that is, as the class-cleansing of central London continues at the current rate.

But what, people needle me, would you do with the Battersea power station site, given that you so strenuously object to its being turned into shiny, happy flats for shiny rich people? The answer is, of course: nothing – just make the structure safe enough for people to walk around and admire it for the Ozymandian monument to Butskellism that it is; or, failing that, raze it to the ground and build the social housing so desperately needed by less affluent Londoners. But there’s a vanishingly small chance of either of these outcomes: why, you’d as likely see a giant pink pig flying between those four iconic chimneys.

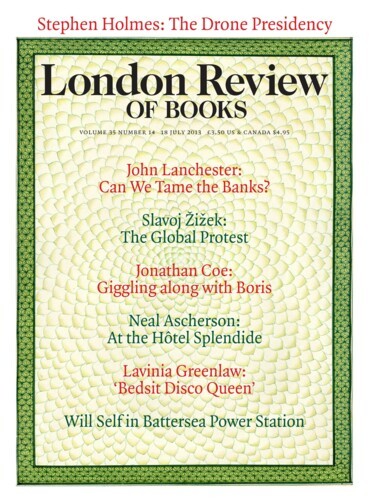

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.