‘Many dentists,’ my mother once portentously remarked, ‘are thwarted sculptors.’ No doubt she herself had experienced their creative frustration – and painfully so. She was wearing a full set of dentures before I was born but never told me exactly when she’d acquired them. Perhaps she’d been presented with a pair (and some sort of voucher for the requisite extractions) on her 21st birthday, or the occasion of her first marriage. As Richard Barnett points out in his excellent text for The Smile Stealers, it wasn’t uncommon up until the late 1930s for young women to receive just such a benison – the reification, if you like, of the great relief to be obtained once those nerve-infested lumps of rotting dentine were yanked from your mouth. Mother used to play with her dentures at unexpected times – pushing out the lower plate so as to give her the gibbous appearance of an Amerindian with a lip-plate. Since she never admitted to wearing them, this was an astonishing coup de théâtre – mounted for me alone. I suppose I could say her performances left me with a fascination for everything carious, but let’s face it: we all have that.

To paraphrase the inscription on car wing mirrors: objects in the mouth can often appear larger than they really are. I’ve had my fair share of toothache and painful dental treatment over the years, but the most excruciating of all has to have been the so-called ‘dry socket’ that I experienced after an extraction. This is when a blood clot fails to form where the tooth’s root once sat, leaving the jawbone open to the elements. It took about a fortnight for the gum to heal, and during that period the wind whistled through the blasted heath of my mouth, while I reeled round town like the fool I am – because the patient information leaflet had warned me in no uncertain terms of just such an eventuality, were I to smoke within 24 hours of the tooth being pulled.

Smoke has, of course, been used as a dental analgesic, as has just about everything else, from henbane to hashish and back again. In truth, I don’t think I could have reviewed this book at all were it not for the efficacy of modern, near painless dentistry: had The Smile Stealers been published even twenty years ago, when my own teeth were still in a shocking state, I simply couldn’t have bitten down on it. Barnett remarks, apropos our formerly agonised mouths: ‘Ask anyone to list the markers of medical progress, and the odds are that modern dentistry will be high on their list.’ Quite so. He also cites the dental torture sequence from Marathon Man as one of ‘the most unsettling moments in 20th-century cinema’. But I don’t need to cast Laurence Olivier as a Nazi torturer in order to wince – only summon up memories of Mrs Uren, the risibly named (to an English child’s puerile ear) French dentist who had to fill every single one of my milk teeth, such was my sugary lust.

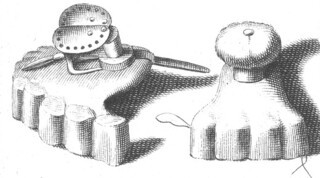

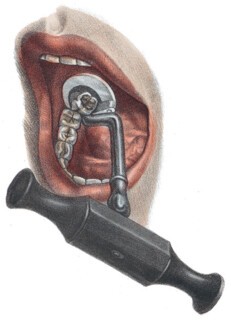

Dental caries, Barnett notes, is principally a disease of civilisation – if by that we mean the sweetie addiction that powered the Atlantic slave trade. But we can find archaeological evidence of dentistry as far back as we care to dig; finely worked gold bridges, set with human teeth, were recovered from Etruscan sites and dated to 700 bce. The Smile Stealers is the third of Barnett’s explorations of the Wellcome Collection, published in association with them, and designed by Daniel Street. They are very handsome volumes indeed, with a heft and solidity, which, combined with an elegant grid and extremely high reproduction quality, give the reader the impression he’s actually wandering through a beautifully curated exhibition, without the bother of having to go to the Euston Road, crane to view the displays, then exit through the gift shop. The aforementioned gold bridges look positively toothsome arranged on the page, as do all manner of sinister screws, picks, keys and clamps used to facilitate medieval and early modern extractions. For, notwithstanding ancient prostheses, yanking the things out was the preferred therapy for thousands of years – the only definitively known way of eradicating ‘the tooth worm’, a parasitic progenitor of toothache believed in by many and various cultures, and arguably the larval form of our much more benign tooth fairy.

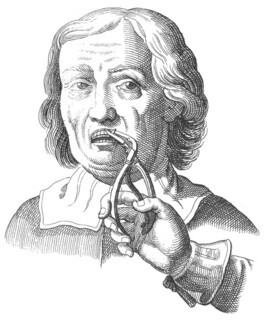

Children’s dental pain may still be alleviated by a coin substituted for a tooth under a pillow, but for adults in the early modern era the sleight of hand (and mind) required was positively baroque: my mother may have believed many dentists were thwarted sculptors, but from the various depictions of tooth extractions reproduced here – many of high artistry – it would appear that plenty of sculptors were also thwarted dentists. I particularly admired the wood and ivory statuette of an early 17th-century extraction, in which the patient is seated on a low stool, while the practitioner zeroes in from the rear, his pelican – a vicious, clamp-like tool – held just beyond the victim’s starting eyes. The tooth-pullers of the Pont Neuf were one of the sights of pre-Revolutionary Paris, what with their carnivalesque costumes, and attendant dancing bears and jugglers – all intended to distract while they extracted. Out in Versailles at the court of the Sun King, courtiers made free with nitric acid, which, while gifting them an ephemeral bouche ornée, speedily stripped the enamel from their teeth. Conspicuous consumption was the status-maker in these halls full of unflattering mirrors, and if it took your teeth to stay in the game then so be it.

The Enlightenment beamed brightly into these benighted mouths: the tooth-pullers gave way to the emergent dentistes, and – as with medicine in general – there was a concerted effort over the next century to raise the occupation to the status of a profession. Nowadays our children (and our children’s children) ‘do nozz’, or inhale the capsules of nitrous oxide more properly employed in soda siphons – I often see the steely rounds that have been ejected into London gutters. The first recorded nozzer was Humphry Davy during his time at Thomas Beddoes’s Pneumatic Institute in Bristol in the late 1700s, but it took another fifty years before dental analgesia became truly effective. In a way – as Barnett’s text makes clear – the whole gleaming and whitened edifice of modern dentistry was raised on a cloud of nozz, cocaine and the latter’s non-euphoric cousin, novocaine. With the patients etherised in the chair, the dentist could really get to work, applying the new electric drills to their foul mouths, with the deftness and accuracy of Eric Gill carving stone freehand.

My own children may do nozz, but between the four of them there’s nary a filling. The fluoridation of tap water has ushered in the full commoditisation of the Western mouth, as Barnett makes clear, while the decline in social medicine (two million dentures were handed out during the first year of the NHS) has reintroduced a market for new forms of quackery. No longer committed to their sculpting, dentists have turned increasingly to expensive preventive orthodontics, tooth-whitening, implanting, and all the other procedures necessary if you want to smile as profitably as George Clooney.

The person I feel most sorry for in all this is my old mate Pete. Like many junkies, Pete had an eye for an unconventional earner: his shtick was to tour the country, popping into dentists’ surgeries, where he’d ask the secretaries if he could have the glass plates smeared with the residue of the amalgam they used for fillings. Once he had enough of these, he’d flog them to metal dealers who could extract the silver from the alloy. Obviously this was a laborious way of acquiring the money required for his next hit of anaesthesia, but you can’t deny that, as with so much we associate with dentistry, it had a certain artistry.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.