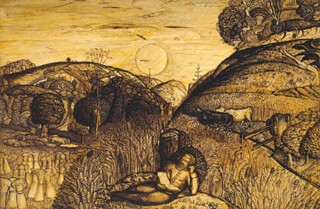

A bearded patriarch, possibly in Elizabethan dress, rests on his elbow, stretched out on a snug little hillock in the middle of a wedge-shaped field of corn. He is leaning against some sort of natural cushion, and it’s possible he is asleep, though he has a large book open in front of him so perhaps it’s just that his eyes are cast down to scrutinise its pages. But that would be difficult since it is evidently night-time: above him, an owl (or perhaps it’s a bat) flies across a large moon that looms over a range of rounded hills. From among them a spindly church spire can just be seen stretching up into the sky; the foreground is filled by heavy ears of corn gathered around the central figure like a comfy blanket. The reclining man is apparently undisturbed by the two hefty cows who, despite the late hour, are making their way through the corn just over his left shoulder – and undisturbed, too, by an insomniac shepherd who pipes to his sheep in a nearby field of standing sheaves, sitting beneath a tree shaped like a lollipop.

Altogether these might not sound like the ingredients of a very satisfactory work of art; but the picture, Samuel Palmer’s The Valley Thick with Corn, conjures a masterpiece out of its incongruous elements in a way that is wholly exemplary of the artist at his best. Palmer’s technique seems to have been unique, a striking combination of intricate pen-work and thick outline done in a gloopy mixture of ink and gum. (‘Outlines cannot be got too black,’ he jotted in his sketchbook in a characteristic spirit of self-exhortation.) The picture is finished off with a varnish that has aged into a rich yellowy-brown: the total effect is sometimes said to resemble an etching, which is true enough, though it resembles something else even more, as Colin Harrison says in his excellent handbook to Palmer: a carved ivory. The Valley Thick with Corn is one of the most beautiful expressions of what Palmer’s son once astutely noted in his father, ‘a certain sentiment of surpassing fruitfulness’, and its fecundity lies as much in its manner as in its subject matter: ‘We must not begin with medium, but think always on excess, and only use medium to make excess more abundantly excessive,’ Palmer instructed himself in his sketchbook. The sheer thickness of the gummy ink feels wonderfully supererogatory, a spirit confirmed in a different way by all the crammed detail that fills the composition: it is a masterpiece of absorbed attention and, blithely at odds with the rules of perspective, it is quite as full of detail in the far distance as it is in the nearground. A cart, as crisply drawn as the old man’s book, lumbers its way up a remote slope, while the distended ears of ripe corn that swell in the foreground are almost comically oversized, as though they had been imported from a drawing of a different scale. ‘There is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion,’ according to Francis Bacon, a remark Palmer considered one of his ‘very deepest sayings’. Topography in Palmerland is usually richly askew, as though the separate elements of its landscape were somehow too exuberantly full of their own reality to be kept within more normal picturely constraints. ‘We are not troubled with aerial perspective in the valley of vision,’ Palmer declared to his sketchbook.

The strangeness only intensifies on deeper acquaintance: the light and darkness of the scene, for example, seem quite independent of any shadows likely to be cast in nature by that immense moon. Oddity in art can be a bravura display of brilliant perversity, like Glenn Gould taking Bach at a counterintuitive lick; but the best Palmer is odd in a much quieter and more mysterious way than that, as though serenely unaware of its own peculiarity. It is hard to imagine an art less calculating: the picture is not the emphatic expression of a personality but more the exposure of one, as though allowing an intensely private kind of idiosyncrasy to reveal itself to a public gaze; and a good part of its quiet power comes from the implicit sense of vulnerability which goes along with that sense of exposure. Here, the feeling of vulnerability finds its locus in the stretched-out reader, heedlessly sealed up in the bubble of his unlikely repose. Palmer was always moved by the mysterious privacy of such self-enclosed figures: dozing shepherds were one of his favourite subjects, and he had a lifelong fascination with a statue in the British Museum that he took to be Mercury asleep (it is actually Endymion) and which he thought of as ‘the sure test of our imaginative faculty’. ‘Bend over it,’ he instructed a correspondent in hushed wonder. ‘Look at those delicate eyelids; that mouth a little open. He is dreaming. Dream on, marble shepherd; few will disturb your slumber.’

The Valley Thick with Corn is one of the six so-called Oxford sepias, a group which now belongs to the Ashmolean Museum. (You can go and look at them in the Print Room, and really you should: seeing the real thing is, in this case, quite unlike seeing the tamed reproduction of the thing.) The pictures date from the beginning of the extraordinary period between about 1825 and 1835 when Palmer found inspiration in the landscape around the village of Shoreham in Kent and produced some of the greatest English pictures of the 19th century. Shoreham for Palmer, like Grasmere for Wordsworth, was not an enchanted birthplace to which he returned, but a deliberately sought-out paradise that he invented from scratch. Palmer had been born, in 1805, in leafy Walworth, but when young had moved with his family to Houndsditch, where his father had set up as a bookseller. Houndsditch was dirty and rough; the contrast with Walworth must have been dismaying, and the boy’s unhappiness was subsequently deepened by the death of his mother and the miseries of school; a subsequent move to Bloomsbury, a much better location for a bookshop, would not have made life feel any more salubrious. Altogether, it is difficult to imagine an upbringing more likely to dispose someone towards thoughts of a bucolic idyll. Most of Palmer’s sketchbooks have been lost, but one that survives, dating from 1824, is filled with dreamy scenes of an English Arcadia, accompanied by statements of pastoral purpose: ‘Whatever you do guard against bleakness and grandeur – and try for the primitive cottage feeling.’ Palmer’s health was never robust and when he began to develop asthma and bronchitis there were clearly practical as well as spiritual reasons for abandoning ‘horrid smoky London’ and finding a rural escape. He had visited Kent and based his drawings on what he saw there, and in 1826 he bought a small rundown house in Shoreham. The cottage feeling certainly was primitive: he called his new home ‘Rat Abbey’.

Palmer’s rural retreat was companionable. His father sold up, followed his son to Shoreham and settled in a spacious house, which was just as well since Rat Abbey could not accommodate many guests and Palmer had numerous visitors. He was the central member of a group of young painters united in their opposition (as usual) to the academic aridity of modern art: they called themselves ‘The Ancients’, among whom the most gifted, besides Palmer, were George Richmond and Edward Calvert. Shoreham for the Ancients functioned as, in Henry James’s phrase, ‘the Great Good Place’ – ‘a valley so hidden,’ Calvert said, ‘that it looked as if the devil had not yet found it out.’ The Shoreham spirit that emerges from the letters and reminiscences seems as much larky as it was rapt, a group of boys inventing nicknames and drinking cider and generally luxuriating in a sense of their own promise. ‘We all wanted thumping,’ Richmond reflected in later life; but perhaps something of their levity found its way into the exuberance of the images that Palmer made there. ‘I believe in my very heart,’ he told Richmond, ‘that all the very finest original pictures … have a certain quaintness by which they partly affect us.’ He means something quite strong by ‘quaintness’, a powerful and indecorous idiosyncrasy, which is certainly what you see in pictures such as The Magic Apple Tree and In a Shoreham Garden – works, Rachel Campbell-Johnston says in her new biography, ‘of mad splendour’.

Palmer has generally been well served by his modern biographers. The landmark in the field is Geoffrey Grigson’s Samuel Palmer: The Visionary Years (1947), still highly readable because animated by all of Grigson’s brilliant erudition and spirit of advocacy. Lord David Cecil’s long chapter in his 1969 book Visionary and Dreamer: Two Poetic Painters (the other one is Burne-Jones) is a more languid affair, but it usefully brought Cecil’s own Romantic instincts to bear on a painter whose inspiration was often professedly literary, and although it is probably a little mannerly for most readers these days (‘Palmer loved to linger by pool and stream. A landscape, to be perfect, must have water in it, said he’), it still serves as the lyrical complement to what is, without question, the most authoritative account, Raymond Lister’s Samuel Palmer: His Life and Art (1987). This irreplaceable gathering of hard-won information sits alongside Lister’s catalogue raisonné at the heart of Palmer scholarship; but it is not always the most atmospheric of books. While Campbell-Johnston doesn’t bring any new discoveries, she does bring some atmosphere. She has a novelistic turn of mind which, while not exactly like Lord David Cecil, nevertheless leavens the data with a spot of fine writing: ‘There was no train to startle the hares from their nibbling or put up the herons from their patient watch,’ and the like.

But behind all these works, the most important thing ever written about Palmer is the Life and Letters (1892) produced by his son, Herbert. It is a masterly and sometimes troubled, sometimes exasperated book, remarkable both for its artistic acquaintance and its emotional intelligence, at once sympathetic and sceptical. Herbert is especially good on the curious vulnerability that forms a key part of Palmer’s art, as it evidently did of his character. ‘A hostile analysis would reveal great peculiarities,’ Herbert says of the Shoreham pictures, ‘but there is nothing commonplace.’ That is praise with some nuance, depending on how you view the commonplace. It is instructive, for example, to imagine the sorts of question that one would never think to ask about the undisturbed gentleman in that field of corn. Does he own the farm? Has he been here long? Does he always dress like that? A painting by Constable, say, might provoke such questions; and even if no answers were obviously forthcoming you would nevertheless feel that the possibility of a thorough explanation lay somewhere within the comprehensive world of its realism. The subject of every canvas by Constable, you could say, is the commonplace and the deep emotional satisfactions of the ordinary: ‘My limited and abstracted art is to be found under every hedge,’ he said. The Palmer effect is quite different: his picture is suspended in an impossible and wholly innocent place, its elements keeping company yet at the same time happily disorganised, like children engaged in what psychologists call parallel play.

Herbert seems to have regarded the whole Shoreham gang with some wariness: ‘a remarkable little clique which no doubt set the whole village agape’. Their pictures of harvest were full of symbolic feeling but perhaps not so full of what harvesting is like: ‘None of the Ancients seemed to know how reaping was done.’ Herbert had similarly mixed feelings about his father’s paradoxically tentative achievement: while he conceded ‘poetic and imaginative faculties of uncommon development’, he felt obliged to note at the same time ‘the technical blunders, and the anomalies, and the absurdities’. The reason so few of Palmer’s sketchbooks and notepads survive is that Herbert destroyed much of what he had to hand on the eve of his emigration to Canada in 1909. ‘Knowing that no one would be able to make head or tail of what I burned, I wished to save it from a more humiliating fate,’ was his explanation, which nicely hits a split note of filial loyalty and impatience with the old man. The 1824 sketchbook that escaped the fire gives some indication of the oddity at which Palmer fils demurred: even a highly informed admirer such as Lister can sometimes sound slightly puzzled about what exactly it is that he is admiring. ‘What animal is represented here is difficult to decide,’ he writes at one point in his usually helpful commentary, The Paintings of Samuel Palmer. ‘It combines the characteristics of several species – donkey, goat, horse, llama – and perhaps it is pregnant.’

Herbert Palmer is finely attuned throughout the Life and Letters, not always comfortably, to that spirit of quiet surrealism that shapes much of his father’s art: the way that, ‘if nature has been consulted, it has been consulted as it were in a distorting glass.’ His clouds, say, look ‘as if you could knock your head against them’, which makes them sound as unlike the miracles of meteorological delicacy to be found in a Constable cloud study as they could possibly be. And he is right: the white clouds in Palmer’s luminously bright cloud pictures (there is one in the Ashmolean, another in Manchester City Art Gallery) are anything but airy and breezy. The Magic Apple Tree struck Herbert as beautiful and peculiar in equal measure: ‘bright crimson apples so numerous and so enormous as far to surpass the utmost stretch of possibility’ – ‘a tremendous and utterly abnormal crop’. The intricacy of Herbert’s final judgment seems to me deeply perceptive about the complicated way that Palmer’s most characteristic images work on us: ‘The result is either impressive or ridiculous according to our capacity of understanding and appreciating the qualities aimed at.’

Calvert would later remember: ‘We were brothers in art, brothers in love, and brothers in that for which art and love subsist – the Ideal – the Kingdom within.’ That sounds a wholly characteristic note of aestheticised piety which Palmer also espoused at his most exuberant. The Ancients got all that from William Blake, about whose feet they gathered in a spirit of veneration. Without obvious irony they called his cramped and shabby lodgings ‘The House of the Interpreter’, after the spiritual authority in The Pilgrim’s Progress; and of them all Palmer seems to have been the most devoted – ‘perhaps the staunchest and most affectionate of all Blake’s followers’, his son observed. Palmer considered Blake the equal of Michelangelo. After a life of poverty and neglect the old man was now in failing health, but to Palmer he seemed ‘energy itself’, a man who cast ‘a kindling influence; an atmosphere of life, full of the ideal’, and ‘one of the few to be met with in our passage through life, who are not in some way or other, “double-minded” and inconsistent with themselves’. The terms of that praise are poignant: Blake’s genius was a product of his single-mindedness, but Palmer’s evidently spoke to, and out of, a much more ambivalent sense of the world, and Palmer was to grow painfully aware that he was anything but consistent with himself. Whether he ever really grasped what Blake stood for, apart from the moral grandeur of his example, is another matter. The works that he responded to most enthusiastically were not very typical: he loved the little engravings that Blake had done on commission to illustrate Virgil’s pastoral poems, ‘visions of little dells, and nooks, and corners of Paradise’. But in so far as they were, as Palmer said, ‘perhaps the most intense gems of bucolic sentiment in the whole range of art’, they were quite unrepresentative of Blake’s genius, which was utterly opposed to ‘bucolic sentiment’. The placid serenity of a green idyll could not have been further from the qualities that got Blake going – energy, conflict, disruption, revolution – and, as Grigson points out in his excellent book, Palmer’s pictures are actually most striking in being so very unlike Blake’s.

His religion and his politics were not much like Blake’s either. During the 1832 election campaign he published a panicky pamphlet in support of the local Tory candidate, in which he attacked the Whigs as the descendants of ‘poor, degraded, dishonoured, Atheistical France’ and sniffed out the Jacobin threat they posed to the established church. That was pitching it pretty high even by contemporary standards. ‘I love our fine British peasantry,’ he told Richmond, ‘think best of the old high Tories, because I find they gave most liberty to the poor, and were not morose, sullen and bloodthirsty like the Whigs, liberty jacks and dissenters.’ He was that rare creature, in Lister’s memorable diagnosis, ‘a Church of England fanatic’. On the other hand, Blake did inform the vision of the Shoreham years in one significant respect: his freedom from adherence to natural fact. That would, as Greg Smith argued in an illuminating recent essay, have set him squarely against one of the main aesthetic assumptions shared by his contemporaries.* ‘Nature is not at all the standard of art, but art is the standard of nature,’ runs one of the aphorisms Herbert transcribed from the Shoreham notebooks: ‘Bits of nature are generally much improved by being received into the soul.’ Nothing could sound less like, say, Ruskin; and while, as it happens, Ruskin did praise Palmer on one occasion for keeping company with the ‘faithful followers of nature’, he must have come to see that Palmer’s interests lay in quite a different direction. Palmer made no further appearances in the pages of Modern Painters. His son, himself a natural historian, observed that he ‘could not have passed the most absurdly elementary examination in botany, entomology, ornithology, or geology’.

Palmer had first met Blake through a common acquaintance, John Linnell, an accomplished and successful artist and probably the most important single influence on the shape of his life. Linnell is the comic monster of the story, a ‘splendid, courageous and manly tyrant’ in Herbert’s view, who would certainly have been played by Brian Blessed had anyone got round to making the TV series. He had individuality like a disease: he was belligerently non-conformist in religion, keeping to a version of Christianity that had been revealed uniquely to him, and he pronounced straightforward English words in a wilfully peculiar way. He was both a driver of hard bargains and spontaneously very generous; gruff and boisterously ungenteel on principle; and he sneezed like a steam engine. Grigson, himself no mean hand at principled enmity, says he had ‘a tendency to hard malice’. He was full of advice, and Palmer took it. He even intervened in some of Palmer’s pictures: Herbert remembered Linnell painting the moon out of one of the Shoreham paintings so as to improve it. Despite being Blake’s patron (he commissioned a series of Dante illustrations that were left unfinished on Blake’s death) he was splendidly unmoved by the mystic impulses of the Ancients. On one occasion he listened to Calvert describing one of his enchanted pictures: ‘These are God’s fields, this is God’s brook, these are God’s trees and these are God’s sheep and lambs.’ ‘Then why don’t you mark them with a big G?’ Linnell asked.

He instructed Palmer to ‘look hard, long and continually’, and to emulate Dürer and Van Leyden, advice that was evidently difficult to reconcile with the militant anti-naturalism he was getting from Blake. In high visionary spirits, Palmer could profess to Linnell his boredom with ‘exhibitions of clover and beans and parsley and mushrooms and cow dung and the innumerable etceteras of a foreground’. But his letters are often painfully docile. ‘Have I not been a good boy?’ he wrote from Shoreham. ‘I may safely boast that I have not entertain’d a single imaginative thought these six weeks, while I am drawing from Nature vision seems foolishness to me.’ Writing to Richmond, meanwhile, he sounded the mixed note of dependence and irritable resistance that would characterise the rest of his relationships: ‘Mr Linnell tells me that by making studies of the Shoreham scenery I could get a thousand a year directly. Tho’ I am making studies for Mr Linnell, I will, God help me, never be a naturalist by profession.’ It is tempting to make Linnell sound like the villain of the story, forcing Palmer against the grain of his gift; and there is obviously something to that. Palmer ‘knuckled under and obeyed’, Campbell-Johnston says, while all the time he was longing ‘to set a visionary imagination free’; but in truth it was probably the mixture of the naturalist minutiae that Linnell encouraged and the spirit of Blakean inwardness that made the magic of the Shoreham idiom possible in the first place – the result being, in John Piper’s well-chosen phrase, ‘half-visionary’.

By the mid-1830s the Ancients were beginning to fragment: Richmond was turning himself into a successful portrait painter and Calvert beginning to decline into esoteric mysteries. Palmer, who had managed to sell almost nothing, was barely getting by on a few shillings a week; in 1832, he bought a house in London and began to give art lessons. (He was by all accounts an excellent tutor and would go on to earn most of his income that way.) He needed money partly because he was keen to find a wife, ‘a nice tight armful of a spirited young lady’ as he put it, ominously enough; and in 1837 he married Linnell’s daughter Hannah, also an artist. The couple set off for a long visit to Italy, burdened by a commission from Linnell to copy frescoes by Michelangelo and Raphael. ‘Italy – especially Rome – is quite a new world,’ Palmer wrote home to his father-in-law, and he soon resolved to change his whole manner: ‘Much as I love England, I think every landscape painter should see Italy.’ The epiphany was down partly to the Italian light and air, and partly to the landscapes of Giorgione and Titian: ‘I can never paint in my old style again,’ he dutifully reported back to Linnell.

‘Both Italy and marriage were fatal,’ Grigson says, bleakly; and Campbell-Johnston doesn’t dissent from that view. There is much to admire in the Italian paintings, but the abruptness of the change of idiom between the Shoreham pictures and A View of Ancient Rome (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery) or Street of the Tombs, Pompeii (V&A) is startling and, in its utter lack of continuity, somehow dismaying. The slight wonkiness of the perspective now seems less part of a rich and informing individuality and more like the work of an unsteady eye. The later paintings are typically full of space and the gradations of what Palmer once called ‘juicy colour’, deploying paint in an attempt to re-create the reality of objects spread out through ‘beautiful distances’; but his genius was never really for the beauty of imagined distances. He was the artist of nooks and shady spaces; and the pictures he did on his return to England only come alive when some of that original inspiration finds its way into them – sometimes incongruously, as when the foreground of a sweeping Claudean panorama is conjured into a cosy Kentish dell, but sometimes more coherently, as in the small number of exquisite engravings he made from 1850 onwards. In these he returned to the world of Blake’s Virgil engravings and rediscovered what Herbert Palmer recognised as ‘the Shoreham power’ that was ‘always ready to awake’.

Sometimes Palmer seems to have realised with pained clarity where his greatness might lie, in ‘poetic compression in antithesis to landscape diffuseness’: ‘Forswear HOLLOW compositions,’ he scolded himself in his private journal, ‘TAKE SHELTER IN TREES.’ The Bellman, an etching left unfinished at his death, felt to him ‘a breaking out of village-fever long after contact – a dream of that genuine village where I mused away some of my best years’. But he grew forlornly convinced that a power had gone for ever: ‘I seem doomed never to see again that first flush of summer splendour which entranced me at Shoreham,’ he told his wife. Buried in his den, an oasis of disorder in his wife’s spick and span Reigate villa, and spending days talking to imaginary friends, he had become a man defined by his disappointment, in a way resembling the spectacle T.S. Eliot once found in Coleridge: ‘For a few years he had been visited by the Muse … and thenceforth was a haunted man.’ One way of dealing with disappointment is to pretend you never cared in the first place; and nothing is sadder in Palmer’s story than his attempts to distance himself from everything that Shoreham had stood for and the ‘positive and eccentric young man’ whom he now barely recognised. Campbell-Johnston remarks on the extraordinary fact that almost all of the pictures that are now most admired were kept by Palmer in a private ‘Curiosity Portfolio’ to which he seems warily to have guarded access as though it were a shady secret. ‘When you see anything very rich, put it into drawing at once – but only a little,’ he advised a student, diagnosing with rueful self-reference the ‘fault of young artists to be struck with richness of nature’. So much for the advice he had once issued to himself: ‘Only use medium to make excess more abundantly excessive.’

Campbell-Johnston is well disposed to Palmer, though she grows as irritated by his pliability as his son evidently was: he appears at one point as a ‘socially inept little man’ who responded to his frequently insufferable father-in-law with ‘tail-wagging gratitude’. She is quite tough on Hannah too, seeing in her ‘bourgeois will’ a version of Linnell’s will to power; but then Palmer cannot have been the easiest husband. It is on the face of it strange that great art should have ever arisen from a cast of mind that Campbell-Johnston firmly calls ‘rose-tinted’, and a period of life during which Palmer was ‘indulging his dreams of a pastoral idyll’ and ‘did not see the realities of rural life’. People who do not like Palmer have always responded to what they see as his escapism in this way: John Berger once expressed disdain for ‘his landscapes like furnished wombs’. Palmer certainly craved ‘quiet, cosy seclusion’, as his son singled out for remark in his memoir, and he relished with a curious intensity the whole idea of the ‘SNUG … how much lies in that little word’. No one modern, no one like us, thinks art should be cosy or snug, and nothing could seem cosier than pastoral, the genre which Palmer especially loved, as his several ventures into poetry confirm:

Low lies their home ’mongst many a hill,

In fruitful and deep delved womb;

A little village, safe, and still,

Where pain and vice full seldom come,

Not horrid noise of warlike drum.

Shepherds who pipe on about their loves and their sheep and lead lives magically in tune with an idyllic and abundant countryside? That is not calculated to tick many boxes in a post-Darwinian age, let alone an epoch of ecological catastrophe; and Campbell-Johnston, who we learn from the flyleaf ‘lives in London and in Norfolk with her family and her flock of sheep’, may justifiably feel that she has the edge on Palmer as far as ovine realities go. Pastoral is deeply unfashionable; indeed the modern preference is firmly anti-pastoral.† Ted Hughes’s windswept and bloody Moortown Diary gives you the daily life of a shepherd as it really is; and Alice Oswald’s Dart translates the lyrical brooks of Arcady into a patiently assembled mosaic of collective memory recording the history of a working waterway. Such literary instincts predate Darwin, of course: when Wordsworth subtitled ‘Michael’, the saddest of all his works, ‘A Pastoral Poem’, he was making a tendentious point about the facts that you might actually face as a sheep farmer, as opposed to the literary stuff you get in one of those ‘pastoral’ poems. Michael ends a broken man, while the boisterous brook of Greenhead Ghyll flows on with heedless vitality. In a good old-fashioned pastoral, nature would have joined in with the human lament, as it does in Milton’s ‘Lycidas’, where the very daffodils well up at the thought that a fellow of Christ’s College might have had the bad luck to drown.

Even its admirers admit that pastoral involves a fantasy about the countryside invented by people who didn’t really live there; but it is easy to make pastoral seem too simple about its own interest in simplicity, and the greatest pastoral (such as ‘Lycidas’) is much more emotionally intricate than a mere longing to regress to the womb. Palmer understood this. He was always a very literary painter, taking inspiration from Milton, Virgil and others; and he was, on occasion, a good critic. In his best essay, ‘Some Observations on the Country and on Rural Poetry’, he discusses superbly the ways in which poetry can entertain and incorporate contrary elements within itself. A simile, he says, ‘at once enriches the subject matter by analogies, and, as opposites manifest each other, enforces it by a contrast’: when Milton writes of a ‘woody theatre’, for example, Palmer appreciates with great tact the way the word ‘theatre’ at once ‘illustrates the position of the trees in ascending ranks on the hill side, and adds to the sylvan quiet by glancing at its reverse, the noise and movement in a place of public concourse’.

Palmer’s own pastoral art perpetually glances at its ‘reverse’, though this is not a matter of incorporating the public concourse but rather a wholly private range of dark experiences that properly fall without the charmed circle of bucolic ease. He was, as Herbert grasped with a son’s harsh patronage, one of those people who found life very nearly impossible. He emerges from the Life and Letters as remarkably tenacious, but nevertheless as one who ‘egregiously failed in the battle of life’; who lacked ‘a healthy mental condition’; who had an ‘almost feminine want of reticence in matters relating to his feelings, griefs and disappointments’; who was prone to ‘a certain morbid and effeminate tendency of thought’. (Herbert viewed what he regarded as the emotional extravagance and effeminacy of the Shoreham circle with evident distaste – ‘There was too much “dearest” about Mr Richmond and sometimes about my father too.’) Palmer considered himself one who had been ‘kicked about in the world’, ill-used and neglected. But the problem of being Samuel Palmer went much deeper than a lack of worldly success, deeper even than the devastation caused by the death of his eldest child. He refers on a number of occasions in the correspondence to ‘my poor mind’, and he could sound more hysterical about his constitutional unhappiness than that: ‘My whole life … has been little more than one continued punishment – flogging upon flogging – each before the last “raw” was healed.’

The central insight of William Empson’s masterpiece Some Versions of Pastoral is that the greatest examples of the form encompass richly contradictory feelings. The life depicted in pastoral is, in one way, perfectly fine and wholly at ease, while being terribly restricted and pinched. ‘In pastoral,’ Empson says, ‘you take a limited life and pretend that it is the full and normal one.’ And this matters because it is what we must do all the time, faced as we are with the awareness ‘that life is essentially inadequate to the human spirit, and yet that a good life must avoid saying so’. In terms closer to those of Palmer’s art, cosiness and imprisonment, snugness and suffocation, are always poised to tip one into the other. Something like this seems to have been at times the reality of Shoreham life. A typical diary entry from the period begins: ‘Thursday. Rose without much horror.’ Whenever inspiration flagged and isolation deepened, as he complained vividly to Richmond, Shoreham life became ‘a living inhumement … turning this valley of vision into a fen of scorpions and stripes and agonies’; and he was ‘pinched by a most unpoetical and unpastoral kind of poverty’. The Empsonian thought that the Shoreham idyll was shadowed by a counter-idyll is, it seems to me, often present in his best pictures. They are things of great shadow and obscurity, many of the best of them monochrome, as though bringing into their removed bucolic space some dark thing that they half-acknowledge. ‘Few people have swallowed blacker doses of suffering than myself,’ Palmer once said, ‘though nobody will believe it, because I am round in the waist and the corners of my mouth turn up naturally.’ The pastoral poem that I quoted earlier can only get at the serenity of its scene by mentioning the pain, vice and conflict that its subject seeks to evade; and the pictures are similarly full of a blackness that accompanies the beauty, ‘as opposites manifest each other’. They are full of enclosures and immense overhanging masses, blossoms and woods and clouds, that certainly promise you a comfy retreat while managing to intimate, at the same time, that sense of life which Palmer described to Richmond as ‘MISERABLY HAMPERED’. Paul Goldman has said, writing of the etchings, that Palmer’s figures are enfolded by the darkness if not usually overwhelmed by it; and the result is a remarkable expression of the capacity of good pastoral art to explore emotional territory way beyond the rose-tinted. ‘Few will disturb your slumber,’ Palmer imagined whispering tenderly to his sleeping Endymion; but the thought of something that might very well disturb his sleepy figures is never far away in his inimitable ‘half-visionary’ art.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.