It comes as a surprise to learn that the second artist given a major show at the Museum of Modern Art was Diego Rivera, for when the exhibition opened in December 1931, the 45-year-old Mexican was already a celebrated Communist. Just as surprising, given that the museum was founded by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and friends, is what Rivera chose to display: five fresco panels devoted to Mexican history from the perspective of the recent revolution, and three others concerning New York City during the Depression. Five of these massive pictures, along with related prints, documents and materials for other commissions, including the famous mural for Rockefeller Center that the Rockefellers first commissioned, then destroyed, are now at MoMA again (until 14 May).

At the time the show opened, Rivera was acknowledged, along with David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, as a leader of Mexican muralism, which was supported by the new government of Alvaro Obregón as a way to promote a transformed sense of Mexican identity through public art. This new identity would yoke an indigenous past to a modern future while condemning a long history of colonial abuse and dictatorial rule. When Obregón came to power in 1920, Rivera was just another bohemian in Paris besotted with Cubism. The education minister, José Vasconcelos, sent him to Italy to study the Old Masters; somehow it was thought that the narrative power of the grand tradition of painting, given over to biblical scenes, powerful lords and wealthy bankers, could be retooled to depict a post-revolutionary Mexico. When Rivera returned to Mexico in 1922 with this new expertise, he set to work on the epic murals – most of which are located in national schools, ministries and palaces in Mexico City, Cuernavaca and Chapingo – that quickly made his name.

In 1927 Rivera was chosen to represent Mexico at the tenth-anniversary celebrations of the Russian Revolution in the Soviet Union. There, as recounted in a catalogue essay by the MoMA curator Leah Dickerman, aesthetic debate was split between ex-Constructivist groups that advocated photographic displays as the true means of collective representation (painting was rejected as bourgeois) and proto-Socialist Realist groups that sought to refunction traditional modes of art for proletarian propaganda. Although Rivera was more sympathetic to the former position (which was advanced by Aleksandr Rodchenko, El Lissitzky and Gustav Klutsis, as well as his friend Sergei Eisenstein), he effectively triangulated the two groups, and the murals he made on his return to Mexico in 1928 combine photographic effects such as cropped figures and massed groups with Socialist Realist motifs like bright flags and cheery peasants.

While in the Soviet Union, Rivera encountered Alfred H. Barr Jr and Jere Abbott, two young American art historians soon to become the founding director and associate director of the Modern, who were on their own sojourn to scout out the Russian avant-gardes. Strange bedfellows, the three made even stranger collaborators at MoMA. That said, Rivera was hardly unknown in the United States; in the news in 1930-31 on account of mural commissions in the Bay Area, he was already presented as a pan-American counterpoint to difficult European modernism – his radical politics notwithstanding, he was at least aesthetically moderate. (His influence on representational art in the 1930s was immense, as evidenced in the work done under the federal Work Progress Administration.) Furthermore, although American capitalists were suspicious of the Mexican government, they pushed for an opportunistic engagement with their disadvantaged neighbour to the south, and cultural exchange in the manner of the MoMA show was part of the programme.

Rivera came to New York only a few weeks before the opening. As frescos are fixed in situ, he had to vary his usual method: he had cement poured into steel frames ready to be surfaced with fresco plaster on his arrival. The Modern set him up in an empty gallery on 57th Street, where he worked non-stop with three assistants, all under the pressure of a steady stream of visitors, a curious media and a tight deadline. The fresco added to the constraints, for in this medium the pigment is mixed into wet mortar, which then dries to a hard surface. Execution thus has to be rapid, which is one reason Rivera favoured graphic sweep, bold massing and broad colour in his murals. Despite its difficulties, he insisted on the medium precisely for its associations with public space and collective viewership. That said, his panels at MoMA, though large (most are five or six feet by eight) and heavy (because of all the steel and cement), were in principle as saleable as any easel painting, and they ended up in collections in both the US and Mexico.

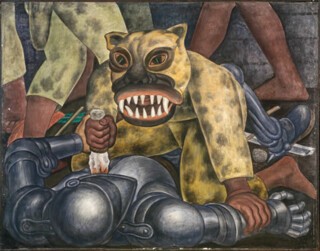

Rivera finished the five murals on Mexican themes in time for the opening, and unveiled the three New York pictures just two weeks later. This was possible largely because almost all the Mexican scenes were adapted from his murals back home. Four of the panels – Sugar Cane, The Uprising (the one newly conceived), Liberation of the Peon and The Agrarian Leader Zapata – present legendary scenes on the road to the revolution: oppressive labour in the old hacienda, police repression of urban workers, the sacrifice of unknown revolutionaries and, finally, the victory of the hero Zapata. In the fifth panel, Indian Warrior, a primitive figure in a jaguar mask straddles a prone conquistador whose armoured chest he stabs with a stone knife; this extraordinary image, Dickerman writes, ‘offers a native Mesoamerican precedent for revolutionary resistance, a distilled emblem of righteous vengeance’.

Nature is sympathetic to the revolutionary spirit in the Mexican panels. In Sugar Cane, the stalks conform to the exertions of the workers, while in Liberation of the Peon, four horses lament a tortured peasant. In Agrarian Leader Zapata, the giant steed that stands with its master approves the final triumph over the fallen enemy (this beast – it is almost a unicorn – shares the pure white coat and dark oval eyes of the hero). At the same time history is understood as sacrificial; Indian Warrior is downright Bataillean. Blades abound in the pictures, even though the swords of the enemy, whether conquistador, soldier or police, are ultimately no match for the stone knife of the masked avenger or the machete of Zapata. In all the panels, Dickerman notes, the bodies of oppressors and oppressed, victors and vanquished, ‘create figural rhymes that speak of shifting power relations across the historical stage’.

Rivera used art history to underscore these desired shifts. His time spent in Paris and Italy is evident in pointed allusions to French and Italian painting. The woman who stands with her child between the police and the workers in The Uprising evokes The Intervention of the Sabine Women by David, and the lacerated peasant in Liberation of the Peon calls up the crucified Christ in Lamentation by Giotto. Here the sacrificial nature of history according to Rivera is both pagan and Christian, as is the mythical gloss that he gave it, and this is why his otherwise weird anachronisms of subject and technique – indigenous and modern, Mexican and European, fresco and steel, history painting and photographic effects – make sense. Across the Atlantic in these same years, Walter Benjamin argued that mass society and mass media worked to erode the auratic basis of traditional art. Rivera wanted it both ways – technological advance in society and iconic authority in art – and sometimes he forced the issue. For example, he had difficulty with his imaging of crowds, which often lump together the very sides he otherwise saw as opposed. Here the ex-Constructivists were perhaps right: photography and film are better suited to such compositions. Yet the force of his pictures is beyond doubt. My childhood home contained only one image I identified as art, a print of the Zapata mural; that a representation of an agrarian revolutionary could find its way into a middle-class house in Seattle in the 1960s attests to its powerful iconicity as much as to its popular circulation.

In the three New York panels Rivera turned from agrarian and revolutionary themes to industrial and capitalist ones. In Pneumatic Drilling (whose whereabouts are unknown) two giant labourers, composed as simple swirls of dynamic lines, bend over power drills, breaking ground for a Rockefeller Center on the rise, while in Electric Power three lone workers toil in three subterranean chambers of a steam plant on a nearby river. The concern of these two murals is the labouring body, often pictured anonymously from behind, with echoes of Realist predecessors such as Courbet (Pneumatic Drilling draws directly on his Stonebreakers), but with the scenes switched from bleak countryside to dynamic cityscape. With the sweep and speed of his execution, Rivera binds these working figures to his own painting body (he was famously rotund; Barr once described him, in his Waspy way, as ‘rather Rabelaisian’), yet this identification does not undo the alienation that Rivera also wanted to convey here. Unlike the natural sympathy of the rural panels, the men in these industrial scenes are connected to their tools and machines prosthetically but not spiritually.

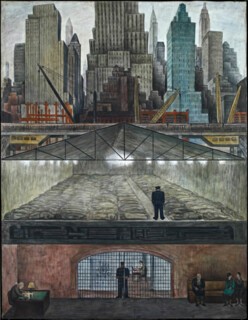

The showstopper in the New York group is Frozen Assets, which presents a fictive cross-section of Manhattan in three layers. In the bottom rank, a caged bank vault is watched over by a clerk and a guard; at a desk inside a woman looks through her jewel box, while on a bench outside two young women wait with an older man (who resembles John D. Rockefeller Jr) to handle their own treasures. In the central rank, a vast hangar is filled with shrouded figures on the floor overseen by another guard (the near twin of the one below). Finally, in the top level, above an elevated platform where an endless line of anonymous workers shuffles to work in trains, the great metropolis rises; three cranes signal that the skyline is in active production. Frozen Assets is an inspired montage: Rivera based the vault on those he had toured in Wall Street and the hangar on the interior of the Municipal Pier on East 25th Street, while his skyline combines a few downtown banks with several new buildings in midtown, including the Chrysler, Empire State, McGraw-Hill, Daily News and Rockefeller Center (the last three of which were designed by Rockefeller favourite Raymond Hood). The allegory of this literal exposé is explicit: the building boom that gave us the great skyscraper city depended on the cheap labour represented by the subway drones and the sleeping bodies as much as on the stashed assets. In this not-so-divine comedy, the pier is a grey purgatory and the vault a brown hell, as much prison as bank (in this faecal cavern, Rivera almost suggests the anal sadism that Freud associated with money). Only the skyscrapers have any vitality, but their animation is fetishistic; indeed, Frozen Assets depicts a fetishisation of capital on a metropolitan scale, in which urban liveliness counts far more than the actual livelihood of working men and women; unlike the labouring bodies in the other murals, they are the real ‘frozen assets’ here.

How did Rivera get away with these pictures at MoMA? Again, his great patron was Abby Rockefeller – wife of John D. Jr, who was caricatured by Rivera, and mother of Nelson, who censored his Rockefeller Center mural. Her support mattered, of course, as did his popularity, but more important still was a public sphere that, in the depths of the Depression, was more capacious politically than anything Americans have experienced since. This was also a time when capitalism could still be grasped, readily if roughly, in terms of class iconography, and when capital was still material enough to be represented by a vault. Our situation today seems very different. If Frozen Assets were updated, what form might it take? How to image our liquid assets, not to mention our vanished ones? And yet the coincidence of the present show and the Occupy Wall Street movement might point to new parallels. The MoMA exhibition opened in mid-November, just two days before Zuccotti Park was cleared by the police and four days before a major demonstration was staged throughout the city, with a nasty confrontation on the Brooklyn Bridge. In The Uprising the police beat down the protesters, and in Frozen Assets the guards watch over the rich and keep the poor in line. They still do. The clash on the bridge had brutal moments, and a common sign at OWS events is ‘Police Protect the 1%.’ OWS demonstrates that the politics of appearance by actual people in real space still counts; it suggests that public art might too.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.