Kew Gardens has supplied the forecourt of the British Museum with an Australian garden. The plants are familiar. Gum trees, for example, fill so many native niches that there is a species to suit almost any foreign habitat (they have had a mixed reception, being fast-growing, which is useful, but thirsty). The BM garden is a long way from Australia as it is seen in the news, which is a place of desert, rainforest and jungle, floods and fires, ephemeral lakes and rivers, and amazing, sudden flowerings when rain comes to the desert after years of drought. As much of the Australian season at the BM is devoted to work by the continent’s indigenous peoples, whose relationship to the land is close, knowledgeable and spiritually intense, it’s as well to be reminded of the flora.

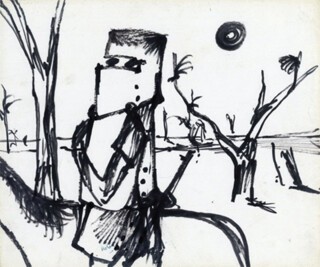

Prints and drawings by aboriginal artists come at the end of Out of Australia, a selection of the BM’s large collection of Australian graphic work (until 11 September). The exhibition begins with figures by Albert Tucker from 1948 and 1950, strongly influenced by Picasso. Further European and American links become clear, but even when artists became semi or totally expatriate, spending long periods in Europe and making reputations there, as Sidney Nolan, Brett Whiteley and Arthur Boyd did, the Australian landscape is often present in their work. The seven Nolan drawings – six of them done with a felt-tipped pen, surely the least subtle of all graphic media – include one of Ned Kelly on a dry riverbed, another in a drought-stricken landscape; and the woods and fields in which the nudes in three etchings by Boyd lie are rougher than European groves and meadows.

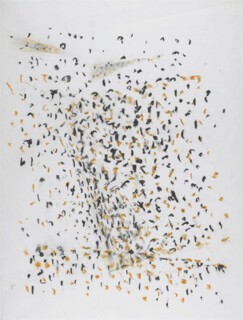

A group of prints and drawings by Fred Williams shows Australian landscape in a way that ignores European ways of shaping a scene. Returning home after five years in London (there is rather dashing aquatint of two dancers in The Boy Friend), Williams said it was seeing gum trees again that determined his decision to stick to Australian landscape. In a drawing of the You Yangs, an outcrop of granite hills south-west of Melbourne, a scattering of small black and ochre squiggles, minimally articulated by four long smudges, could be an abstraction: the work derives, however, from sketching expeditions Williams made in the hills, and once you are told to read it as a landscape, the squiggles as trees, the smudges as hills, you see it with more pleasure. In an etching, Circle Landscape, Upwey, in which the squiggles condense into a forested hillside, the flavour is Oriental. In others that show chopped trees or ferns putting out new shoots after a fire, the line is angrier. Once again the subjects need captions. In 1969, Williams began painting a series of generic Australian landscapes in gouache whose flat monochrome backgrounds in sandy and rocky colours and the bright marks dotted over them, are close to pure abstraction. Then, in the latest of his gouaches here, a 1975 view of sand spits and sea, stretched out brush marks paraphrase the detail of landscape elements in much the way Ivon Hitchens paraphrased the lusher facts of English ponds and woods. It is a return to simple representation.

Williams found a way of painting and drawing the country that can be related to abstract practice elsewhere, but its pictorial conventions are his own. He isn’t experiencing his country through anyone else’s eyes. A sense of deep engagement with the country and its history is even more strongly present in a group of works by Aboriginal artists that draw on styles (dot painting) and traditions which are entirely native. The catalogue notes let you know the extent to which these pictures are visualisations of legends, places and events. Take Dancing Up Country, an aquatint by Dorothy Napangardi made up of hundreds of small white dots. They form a regular grid over which broader skeins flow – think of the lights of a city where a freeway crosses suburbs seen from a plane at night. Even when you are told what it represents – ‘chaotic and violent encounters between … two groups of ancestors’ that ‘established a precedent for social order and the law’ – you can’t read it as you can Williams’s landscapes. But knowing that it illustrates an idea explains the sense you have that this is more than pattern-making.

The baskets made by indigenous Australians shown in the next room, many of them masterpieces of the craft, are all from the BM’s collection. Some are new but the majority date back to the 19th century. I have always cherished the theory that the handbag, the artefact that freed human beings from the limitations of eating food where they found it, was crucial to our development as social beings. The importance for those leading the peripatetic life of having things in which to carry other things is apparent in the uses to which bags were put. There is a reproduction in Lissant Bolton’s Baskets and Belonging (British Museum, £9.99) of an early 19th-century illustration of objects made and used by Tasmanians. It shows the basics of a material culture: weapons, personal decorations and things to carry things in. As well as spears, clubs and a shell necklace, there are two containers, one cut from a large bull kelp leaf that is small and intended for carrying water, the other a basket. The unique surviving early example of the former – it is only 18 centimetres deep – is in the exhibition. An account from 1792 informs us that ‘a member of the d’Entrecastaux expedition saw baskets filled with shellfish and lobsters’, while others contained ‘pieces of flint and fragments of the bark of a tree as soft as the best tinder’. An 1880 photograph has an old man, dressed as he would have been in his youth, holding a club and shield and with a club basket over his shoulder. From lists of basket contents and uses you learn that there were special baskets made to carry the dried bones of a dead child or even to store a baby’s umbilical cord, baskets lined with beeswax to hold honey, baskets to catch fish or to hold needles and thread.

Bolton says that the ‘riches’ of the people who made the baskets ‘were and still are intellectual, philosophical and religious’. This did not prevent the skills that went into cane preparation, twining and knotting, shaping and decorating, resulting in objects that are simply beautiful. Take a particular kind of basket from the rainforests of north-eastern Queensland, called ‘bicornual’ because of the projecting points of its two-cornered base. Its sculptural curves are emphasised by the way the strands of cane from which it is made follow swelling contours. It is a wonderful, evolved design. Here, as with the texture of the looped and knotted bags, also from Queensland, pattern-making is disciplined by materials and use. The baskets are as visually satisfying as any of the works of art next door.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.