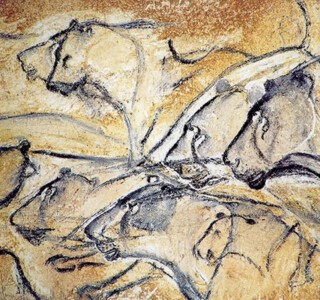

An unknown number of years ago a rockfall closed the entrance to a cave in the limestone gorge of the Ardèche river in France. In 1994 three speleologists found air wafting from an opening, cleared a way in and discovered caves and grottos running 400 metres or so into the rock. The walls are lined with drawings of animal species – bison, lions, bears, horses, aurochs, deer and rhinoceroses. Some show whole animals, standing or in motion, others overlapping rows of horses’ heads, delicately outlined and smudged. Rows of lions’ heads cross the wall like a hunting pride. What is right is so right that you nearly believe a rhinoceros with a huge curving horn really existed too.

A radiocarbon date of 32,000 years makes the drawings in the Chauvet cave (named after the leader of the team that discovered it) the oldest known Palaeolithic cave art – the paintings at Lascaux are only around 17,000 years old. The date so contradicts ordinary stylistic assumptions that there still are archaeologists looking for a reason to push it forward: could the carbon-dated charcoal used in the drawings have been made from fossilised wood?

Werner Herzog persuaded the authorities to let him make a film of the site. Cave of Forgotten Dreams, a 3D documentary, has just been released. Most art documentaries show you things that are no more than a plane ticket away, and the best of them send you back to the originals: what Herzog filmed in the Ardèche can’t be visited and will not be filmed again soon. The lesson of the damage done to the Lascaux paintings – where humidity set mould growing – has been learned. Only a few people with very good reasons are allowed into the Chauvet cave. Herzog’s film is a version of a sequestered original, like a photograph of a painting kept in a bank vault. Still photographs won’t soften the desire to see the drawings themselves, nor will the planned replica of the cave that may be built, following the model of Lascaux II. Herzog leads you to a place you will never visit and the sense of being inside the cave that the 3D image produces makes it all the more tantalising. You want to get your own torch and walk where the film-makers walked.

The caves themselves and the character of the drawings on the walls arouse distinct responses. Herzog is inclined to see the caves as chapel-like – and there is, to be sure, one possible altar with a cave-bear skull on it. But to absorb the cave art into a spiritual context requires analogies that veer off speculatively, many of them drawing on modern anthropology; for example, one of the experts whom Herzog interviews assumes that an Australian Aborigine will have privileged insights.

The drawings, wonderful pieces of observation and transcription, can prove nothing. Imagine that by some miracle of time travel the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel had been transported and inserted into the Chauvet cave while the Palaeolithic artists were at work. When their flickering torches lit up the creation of Adam what would the artists’ response have been? Surprise that humans were the subject matter? Excitement perhaps, in recognising the potential of a body in perspective? Would they have preferred their own animals, seen clearly in profile? They would surely have felt that here was someone doing what they did: mastering the art of drawing on a wall. But what could they have guessed of the painting’s wider meaning? And then, how necessary is that meaning? All over Europe at this moment there are plenty of people in galleries and churches who, even when looking at pictures from their own traditions, are untroubled by their ignorance of iconography and show little inclination to absorb what they are seeing into a spiritual exercise. They get pleasure from obscure Chinese, Indian and African art. It is more often subject matter than a story that draws us to pictures. The wonder of the Chauvet drawings as images has long outlasted any unguessed-at ceremonies they may have been used in.

Which is not to say that one isn’t curious about the people themselves or grateful for Herzog’s conversations with those experts who, each in their own way, open narrow windows on Palaeolithic life. One man dresses in animal skins; one demonstrates (with less than Palaeolithic skill) the use of a spear thrower; another shows how ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ can be played on a reconstructed Paleolithic flute. There is a discussion of prehistoric ‘Venus’ carvings: was their purpose religious, feminist, erotic?

We surely have an innate grammar of representation in common with the individuals who made the drawings. To direct attention to the look of something, most of us will, at a pinch, reach for a pencil and say: ‘It goes like this.’ Children draw families, houses, the sun. Boys draw robots and cars. Girls draw girls. Men draw diagrams. Some of us go on from the schematic to the realistic. Those who drew on the walls of the Chauvet cave direct attention to the animals they hunted or were hunted by. Those who made the drawings – and my guess is that there were only a few of them – were specially good at it. Through the drawings one learns how impressive the bulk of the bison must have been and how threatening the sway of a stalking lion’s back.

In a coda Herzog takes you to a nearby tropical greenhouse project, built round the warm water of the cooling system of a nuclear power station. Reptiles breed happily in the stream. The last animal image you have is of a young mutant albino alligator. It is not at all clear how this fits in, but I almost went away to try to draw it. Had I done so I would have found how much less I knew about it than the least of the Chauvet artists knew about their subjects.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.