The Three Kings in Jan Gossaert’s Adoration of the Kings are lavishly dressed and richly supplied with gifts. The building in which they have discovered the Nativity is a handsome ruin. The arrangement of figures and walls is solemnly vertical. The painting is dated between 1510 and 1515 and is the finest in Jan Gossaert’s Renaissance at the National Gallery (until 30 May). A new catalogue raisonné, which includes all his work, not just what is shown here in London or what was seen in the companion exhibition in New York, persuades you that it was his masterpiece.*

The painter’s attention is of the kind that lets no part of the surface merely suggest fur, flesh, cloth or metal – he includes every hair and stitch. Oil painting like this was the North’s gift to the South. Ways of animating and exploring the look of the naked body were taken north. ‘Better at painting than drawing’, Dürer, who saw and admired Gossaert’s work, wrote in his travel journal.

When in 1508-9 Philip of Burgundy travelled with his entourage to see Pope Julius II in Rome – the profitable right to appoint bishops was under negotiation – Gossaert accompanied him. The handful of drawings of Roman relics that survive show a Flemish sensibility accommodating itself to new forms of sculpture and architecture, though the rather nervous, fussy hatching indicates that this wasn’t achieved without strain. Still, what he took back home was enough to have him credited with introducing mythological subjects with nude figures to art north of the Alps: the ‘Man, Myth and Sensual Pleasures’ of the catalogue’s title are represented by the heavily muscled, well-fleshed figures derived from classical sculpture that Gossaert painted from his return from Rome until his death in 1532. The thin, almost emaciated naked bodies of earlier Flemish crucifixions and martyrdoms, and the smoother, relatively slim figures of, say, Van Eyck’s Adam and Eve in the Ghent altarpiece of 1432, ceded place to Gossaert’s thickly muscled, anatomically detailed living statues – not impossible figures, but all closely modelled on a few sculptural types. They seem to belong to another race – well-nourished clones escaped from the studio of a Pygmalion. It was a turning point.

Very little is known about the detail of Gossaert’s life and character but he was a court painter and never established a large studio. One must assume that the taste of his patrons is legible in his work no less than his own. Sometimes the connection is straightforward. The earliest of a group of mythologies is Neptune and Amphitrite (1516), painted for Philip of Burgundy, admiral of the Burgundian fleet from 1502 to 1517. The naked figures stand side by side, arms over shoulders and round backs, the same pose as the Adam and Eve of 1520 in the picture from the Royal Collection. In an earlier picture of 1510 closely based on Dürer’s engraving, the couple stand apart, with space between. Snuggling up comes in stages: Hercules and Deianeira (1517) twine their legs together. The slightly soppy clean-shaven Neptune’s most striking oceanic attribute is a pointed conch shell covering his penis. It was not just mythological characters who were made more solid, foreshortened and twisted, but religious ones too: Adam and Eve embrace more closely in drawings from the 1520s, and the Christ child becomes fatter, a toddler not a baby, stretching towards you or away, rolling and reaching.

Because no detail is skimped, and few backgrounds are left very plain, architecture sometimes embraces the figures who embrace each other. The classical detail can be profoundly incorrect. In the Neptune, for example, there are bucrania inserted below triglyphs, not where they should be in the frieze. But there are also intricacies of Gothic tracery and classical ornament that are both perfectly rendered and used to project or embrace the figures who are the painting’s subject: proper designer’s work that has not declined, as such details easily can, into ramshackle approximations. Mythological figures inhabit sculptural niches, saints and Madonnas gather under Gothic canopies. In the portraits fictive painted frames project figures forward while the clothes of the sitters are often masterpieces in their own right.

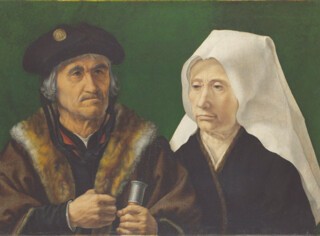

In three of the best portraits a man looks out at you, not over your shoulder. Were they people Gossaert knew well? Two seem to be. One in a red hat makes a gesture towards you as he would to a friend, the second, in a black tricorn and fur-lined coat, almost smiles as he half-raises an eyebrow. The third is more difficult. His lips pursed, his head a little back, he is writing a note and challenges the painter, who has also recorded the files pinned to the wall, as well as coins, scales and sealing wax. Possibly he is a tax collector. The even, Holbein-like attention to flesh and objects is more telling than the equally detailed rendering of the slashed tunic worn by one man – perhaps Charles of Burgundy – which says no more about his impassive face than ‘I am rich and powerful.’ That painting probably wasn’t made from long sittings as the others may have been. The old couple in the National Gallery’s double portrait (shown here), his mouth firmly closed, her brow creased, look an unhappy pair. Their expressions go beyond the impassivity of mere record, seeming to make a point of saying: ‘This is how we were, you may as well know it.’ I can’t think of a modern equivalent except perhaps photographs you wouldn’t put in the album.

It’s hard to take delight in the direction Gossaert was leading Flemish painting, at least until you think of Rubens and his contemporaries lying ahead. In the Adoration Mary and Jesus still have the decorum that is lost when, in later versions of the Virgin and Child, Gossaert makes the child a muscular cherub and the mother a pretty nursemaid. One of the editors of the catalogue raisonné, Maryan Ainsworth, makes a radical alternative proposal for the authorship of the head of the Virgin, and maybe of the child too, in the Adoration: that they are the work of Gerard David. The matter seems beyond any sure adjudication and one would be unwilling to credit the emotional centre of the picture to a hand other than Gossaert’s. Yet it is easy to regret what was lost when he met demands for coarser, more erotic subjects and a more athletic way with bodies.

The exhibition touches you in a way the Pre-Raphaelites would have recognised when they found virtue in stiffness and detail. In the Adoration the child sits as new babies do – there is a realism here that the cherub-derived children don’t have. His mother also has a solemn humanity that was later lost.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.