If you grew up in the 1940s and 1950s anywhere in the English-speaking world where American magazines were more likely to be found than European ones, places where the culture was popular not high, then a pile of the Saturday Evening Post with Norman Rockwell’s covers was likely to have been a solace, and an entertainment. In my case it was New Zealand. My wife remembers sharpening her wits on the Post’s ‘Perfect Squelch’ column. I found a pile of Posts in the alcove of the hospital where the shrouds were stored when I had a holiday job as a porter. At home it was airmail copies of the New Statesman and the occasional New Yorker. I was doubtless snobbish, but not to the point of ignoring visual and literary fast food.

The Post was full of images that made no concession to hierarchies of taste. My mother’s copies of Vogue, with black and white photographs by Penn, Avedon and Horst, and drawings by John Ward, Bouché, Eric and the rest, are still my best notion of what a sophisticated magazine should look like. The Post, with its Rockwell covers and advertisements for refrigerators of giant size, finned cars, and kitchens in which slim housewives lived the dream with a smile, was quite the opposite: not smart, beautiful and distant, but almost available, maybe coming soon. Pop Art in the 1960s would mine this imagery with envy, anger, irony and glee.

The boy with a pile of the Saturday Evening Post among the shrouds would almost make a Rockwell cover. So, even more plausibly, would the boy looking at his mother’s fashion magazines. Rockwell would have expanded them into anecdotes. It is the nature of the anecdotes, the subject matter, not the artwork, and the way the style of the latter was adapted to the needs of the former that the exhibition of Rockwell’s work at the Dulwich Picture Gallery (until 27 March) brings to one’s attention. It includes the originals for a number of illustrations, some printed versions and a handful of studies. There is a long run of Post covers.

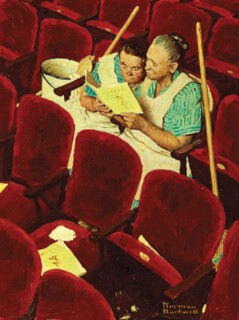

The artwork is pukka oil painting. American illustrators more often than English ones trained as painters. When photograph-engraving came to England, the Punch illustrators and others whose work had been reproduced as wood engravings went on working in line, or turned to watercolour but rarely to oil. Rockwell, particularly in later years, rummaged in the graphic toolbox for whatever was handy. If a photograph was a quicker way to record a pose, if painting over it gave you the information you needed to set up your cover of two cleaning women sitting in the stalls in an empty theatre, why not? The end to which Rockwell worked was the telling image, not the precious artefact. Or even a distinctive personal angle on things seen. You recognise his covers but the drawing, both characterless and competent, reads as a task not a pleasure. Steven Spielberg and George Lucas admire and collect the paintings – not surprising, since they work in the same genres. Their films, like Rockwell covers, deal in constructed worlds and multiple sources.

The souvenir volume that stands in for a catalogue for the Dulwich exhibition has a note by Ian A.C. Dejardin, director of the Dulwich Picture Gallery.* It begins with a quotation – ‘Rockwell is terrific. It’s become too tedious to pretend he isn’t’ – and goes on: ‘So famously wrote the New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl in Art News, September 1999.’ You have a sense of Dejardin breathing a sigh of relief – not that he can have had any fear that the great art at Dulwich would be sullied. In a world where Jeff Koons operates there is no need for even the most fastidious director to falter at the vulgar and sentimental, no need for knowing irony. Schjeldahl’s ‘go on, you know you love it’ makes snobs of those who draw back. Nor, in describing what he likes about them, is Dejardin wrong. Rockwell did heighten the comic moment – hammed it up. The gestures and expressions, like those in silent movies, caricature real frowns and smiles – over-salt and over-sweet.

Coming back to Rockwell made me sentimental about the past. But not about the art. He was a terrific phenomenon, not a terrific painter. Cute sentiment and worthy intentions fail to revive whatever it was that worked half a century ago. For all the detailed rendering that went into some of them the covers portray scenes from charades or items in a theatrical revue: the girl in the jury room who won’t change her mind, the dog that holds up the traffic, the breakfast table argument, the boozed-up skiers who make a trip to the mountains jolly hell for a middle-aged man in his neat overcoat. Raising the seriousness quotient for a Thanksgiving dinner changes nothing. Rockwell’s America is a summing-up of hopeful platitudes and winsome notions.

The display of covers in the exhibition shows things I didn’t know or had forgotten. For example, right through the 1920s and 1930s the figures – single or in pairs – were cut out against white backgrounds. It was only in the following decades, when his record of the look of small-town America and its inhabitants (often his own neighbours) offered a folksy version of the American dream that backgrounds with a mass of detail became the rule. Not that he failed, when he stopped working for the Post and made illustrations for Look, to respond to what was changing; there is a study in the exhibition for the picture of Ruby Bridges being escorted to her place in a desegregated school in New Orleans in 1960. But drawn illustrations of current civil crises were by now an anachronism. Photography had long taken on that role and in the middle decades of the century it was photography that showed America to itself.

Yet there are aspects of American reality that do belong to painters: to Hopper, or Eakins, or Hood, or Bierstadt, or Winslow Homer, or to quite thin commercial art like Charles Dana Gibson’s Edwardian girls, or to Thomas Hart Benton’s agrarian patriotism. That older work shows illustrators and painters finding things no one else had quite seen, things that would thereafter infect the visual culture. The Steinberg exhibition at Dulwich showed that you didn’t have to be a thoroughbred American like Rockwell to tell the country things about itself.

If the Rockwells were shown at Tate Britain, not Dulwich, which has no holding of 19th-century narrative painting, you would have a better way of placing them. When I look at narrative pictures by Martineau, Orchardson, Luke Fildes, Millais, Tissot and so on I am willing to agree that, sentimental, finicky, predictable though they sometimes are, it is too tedious to deny that they are from time to time terrific. Rockwell, many years on, doesn’t rise to the occasion in the same way.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.