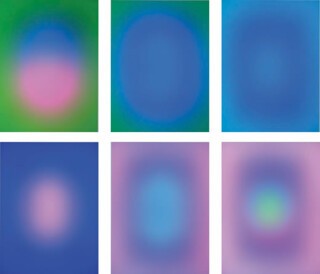

When you shut your eyes you still see. If the light is strong you register a red haze as it passes through your eyelids, or the retinal after-images of bright objects. But even without residual inputs, even when there is nothing you can be said to have looked at, you still see spots and flashes and more organised phenomena like the fringe patterns that go with some headaches. That kind of brain-generated seeing, which has no starting point in seen objects, is one source of James Turrell’s art. Another is the experience of space without reference points, as in a white-out when snow and mist remove all indication of near and far, or its converse – the absolute darkness of a blacked-out room. Indeed Turrell seems to find sources for his work in anything that separates light from substance, any situation where colour is abstracted from the thing it colours, light from its source and from the thing it illuminates. Secondary attributes which philosophers sought to distinguish from solid objects become primary.

In the Turrell show at Gagosian’s Britannia Street gallery there are four exhibits. First, aerial photographs and cutaway models (sculptures really) of the Roden Crater, the 400,000-year-old, three-mile-wide extinct volcano in the Arizona desert that Turrell bought in 1979. By carving out viewing chambers and tunnels and building stairways he is in the process of making a naked-eye astronomical observatory, larger than – but in the spirit of – the Jantar Mantar at Jaipur or Stonehenge. Second, Sustaining Light, a five foot by four foot aperture which slowly changes as the light from unseen neon tubes, changing in a computer-driven sequence, stains the field with merging clouds of colour. Third, Dhatu, a large white room, entered through a square opening by way of a ziggurat of stairs. Inside the room changing light transforms your experience from a whited-out absence of features to brightness. An aperture in the far wall, the shape of an enlarged airplane window, changes in concert with, or in contrast to, the colour and intensity of the ambient light.

The fourth exhibit is Bindu Shards, part of an ongoing Perceptual Cells series. This is a light work experienced by one viewer at a time. You sign a paper confirming that you aren’t epileptic, choose between hard and soft versions of the experience you’re about to have (I chose the hard one), and lie on a bed that slides through a panel into a spherical chamber where, for 15 minutes, you look up at a featureless dome as the lighting changes in colour and intensity. The consequences are astonishing. Strong colours – red, green, blue I think, but it is hard to remember – come and go. You find you are seeing patterns – fields of cells, bubble shapes, lines. They arise, we are told, from the Purkinje effect. (Purkinje was the first to examine the way things seen in dim light lose their colour.) The rods and cones of the retina have different sensitivities; if I understand it correctly it is the quick transition from light to dark in Bindu Shards, from full colour to monochrome sensitivity, from daylight to moonlight, as it were, that pushes one’s brain into pattern making.

Some of the rare experiences in everyday life that Turrell’s installations replicate – the Purkinje patterns, for example – take place within the confines of your skull; others reduce changes in the natural environment to the dimensions of the gallery: white-outs, total eclipses, sunsets, waking to find snow has fallen, watching a power failure douse the lights of a city.

The gallery pieces are a reminder that Turrell’s first degree was in perceptual psychology; the Roden Crater prints and models that he studied astronomy and had a pilot’s licence at 16. The photographs of the crater and its surroundings (the closest conurbation is Flagstaff) were taken with the kind of large-format camera used for aerial mapping (read-outs of time and other data appear in the margins). Turrell made long flights over the desert before he found what he needed – a regular cone of modest size, not too close to horizon-occluding features. The observatory has been long in the making – a website says it may be open to the public next year; photographs suggest that, like Walter De Maria’s lightning field in New Mexico and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, it will become one of those places of pilgrimage, which for one practical reason or another are very difficult to visit except in the imagination.

They stand, those iconic works, as examples of art that cannot in the ordinary run of things be exchanged in the market; they tend to become the responsibility of non-profit institutions like the Dia Foundation. Their art historical roots are in the 1960s and 1970s, the ethos is West Coast, not East. Because Turrell’s aesthetic has origins in physiology and psychology, astronomy and the physics of light, because there is a craftsmanlike attention to detail, it engineers responses very precisely and is almost what art hardly ever is, genuinely experimental. Well-made apparatus can be satisfying in its own right (I wish I had paid more attention to the channel of light sources I glimpsed when I looked out from the Bindu Shards bed) but the physical presence of art is not always necessary for it to be effective. Mere descriptions, particularly of minimalist pieces, can sit in the memory quite as long as paintings and sculpture seen in galleries. Many years ago I read about a work by Robert Irwin, in Venice, California. In 1980 he was invited to create an installation for a new gallery – a large space at street level. He adjusted the skylights, painted the walls white, knocked out the wall facing the street and replaced it with semi-transparent white scrim. ‘The room,’ Lawrence Weschler wrote, ‘seemed to change its aspect with the passing day: people came and sat on the opposite curb, watching, sometimes for hours at a time.’ I would like to have seen it, but I am happy to imagine it now it is long gone. Turrell’s light pieces, despite extreme technical competence and refined presentation, positively ask to be liberated from physicality. The exhibition closed on 10 December.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.