Over the years the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square became a focus for attitudes to monuments and monumentality. There was no agreement about which person, victory or event should be celebrated, and little confidence that any modern sculptor could manage the sorrow, patriotism, nobility, admiration, pride and so on that would once have seemed appropriate. There were those who lobbied for statues of Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park or Nelson Mandela, but it was in the end decided that the answer was a cycle of temporary pieces. That is now in progress. (The statue of Mandela ended up in Parliament Square, and a few weeks ago a bronze statue of Sir Keith by Leslie Johnson – a bigger fibreglass version of it did have some time on the plinth – was unveiled in Waterloo Place. Park looks across the space in front of Decimus Burton’s Athenaeum, under the nose of Edward VII’s horse, towards Captain Scott. Here, at the head of the steps leading down to the Mall, chaps in bronze, holding their ground among the stucco and the trees, can forget the teeming, agitated crowds which offend their fellows in Trafalgar Square.)

Of all the pieces that have been given an outing in the square Rachel Whiteread’s translucent replica of the plinth, set on top of the plinth itself, was the easiest to read as a comment on the problem of how to make a monument in an un-monumental age. Its dimensions – it was big: no sculpture in the square matches, as hers did, the volume of its plinth – and its translucence might, if you chose, be given a meaning, but not anything as precise as a list of battles, or even anything broadly symbolic, like G.F. Watts’s Physical Energy (represented by a naked horseman) in Kensington Gardens. Whiteread’s plinth-on-plinth had monumentality without being a monument, you could think of it as a snuffer extinguishing any flame from the embers of old expectations that might flare up from the plinth below.

Most of her other large-scale work consists of similar replicas and positive and negative casts: of a room (Ghost, 1990), of a house (House, 1993), of a New York rooftop water tower (Water Tower, 1997). They are as open to personal interpretation as the plinth and, like found objects, as powerful or delightful (or frightening or horrid or funny or strange) as you like to make them. On the other hand, the meaning you give to the casts of rows of outward-facing books (you see fore-edges, not spines) that make up the sides of the Holocaust Memorial in Vienna is constrained. The feelings about what is appropriate to a monument that gathered around discussions of the fourth plinth in London were dwarfed by those produced by an infinitely more troubled political, cultural and historical context in Vienna.

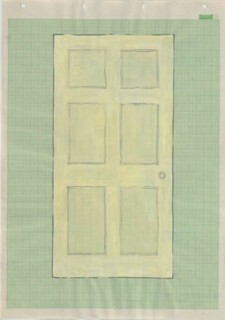

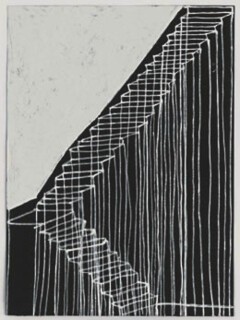

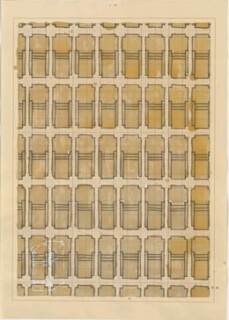

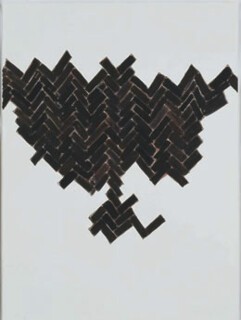

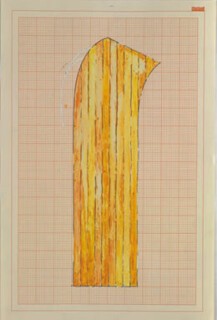

There are sheets relating to all these large works in the exhibition of Whiteread’s drawings at Tate Britain until 16 January, but there are a few three-dimensional pieces too, including a maquette of the Vienna memorial. While the sculptures, no matter how ordinary the objects that are their starting points, are weighty, solemn even, the drawings, even when they are drawings of those pieces, are light, charming, sometimes pretty. It’s partly a matter of materials. The images are mainly patterns, plans and elevations, all fairly neatly hand-drawn (sometimes coloured), mainly in ink, most shapes quite (but not too) tidily filled in with white gouache, pale watercolour, acrylic, crayon, resin or varnish. Among the groups set out in the list of plates in the catalogue (from the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles where the show originated) are ‘tables and chairs’, ‘floors’, ‘beds and mattresses’, ‘house and stairs’. Some show arrays (Twenty-Four Switches Both On and Off) while chevron-patterned tilings suggest the sculptor is a recorder of architectural salvage. It is not unusual to spot a joinery detail, like the ‘ears’ at the top of Sash Window or the nicks taken out of the corners of the rectangles in One Hundred Spaces, which seem to relate to the construction of tables.

The drawings are hand-made representations of hand-assembled objects, and the contrast of the drawn lines to the mechanical rulings of the pale graph paper many of them are done on offers a rough/neat sensation that is a bit like the sweet/sour or hot/cold sensations you get with food. If they were perfectly done – by a computer, say, that would be lost. Like the evidence the sculptures give of the nature of the things they were made from (the dye stains in the plaster from the binding cloth of cast books, the imperfections in carpentry recorded in casts of furniture), they mediate a romantic minimalism. The outcome of a technologically sophisticated use of the same materials to produce an immaculate product would be classical and chilly.

The frugality of means and materials in these drawings reprimands our propensity to covet and collect objects that too quickly become trash. If we visit an empty house, the absence (made evident by marks on the walls) of pictures, the opportunity to cross the naked floors of empty rooms unimpeded by furniture, and the ability to look out of uncurtained windows can make the home we have come from seem intolerably full of stuff. Whiteread’s drawings bring those sensations to mind.

But we must have our things – children make fetishes of toys and we do too. The last room contains two shallow wall cases, both as anti-monumental as you can get and, as artworks, as frugal. One contains variously manipulated postcards – drawn over, painted over or punched. The work done on the views of places and buildings isolates fragments: the effect, on a small scale, is not unlike that of Whiteread’s House.

In the other case shallow shelves are filled with small objects – she calls it a ‘visual essay’. There are made things: miniature wooden wood-working tools, toy furniture, little shoes and casts of shoes, a cast of a human nose, flat wooden spoons and oddly flattened metal ones. There are natural objects: fossils (a fish, an ammonite), minerals, pieces of rock. There are useful things too: a corkscrew, shoetrees, a linotype slug spelling out Rachel Whiteread in italic, a whole box of mother of pearl buttons. Many people gather similar cabinets of curiosities – there is pleasure in being your own curator, and we all are in one way or another. What’s interesting here is that while there are things you could reckon quaint, and some that must be personal, sentimental even, there are others that seem to give access to a sculptor’s way of looking and thinking. The amateur maker of such a cabinet might include the fossils and shoetrees, but the pair of door handles and the yellow plastic inflatable child’s swimming aid (I think that’s what it is) would have been less likely to go on the mantle shelf. Here, as in House and Ghost, you take pleasure in being made to look at ordinary things with the degree of attention that art presumes.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.