He was Edward Muggeridge and 22 years old when he left England for America, Eadweard Muybridge when he returned 40 years later. He was English, born in Kingston upon Thames in 1830. He died there in 1904. But it was California that made him a photographer. The largest item in the exhibition of his work at Tate Britain (until 16 January) is a mighty 360° panorama of San Francisco, taken from the tower of the house of one tycoon and looking down on the house of another, Leland Stanford. The houses, large, but crowded together on the slopes of Nob Hill like limpets on a rock, are new, the environment treeless. San Francisco was expanding, a lot of money was being spent, and the results were florid: one of Muybridge’s commissions was a series of photographs of the interior of the Stanford mansion: dark rooms, much carved and polished wood and stone, heavy drapes setting off white marble statuary.

San Francisco, made rich by the goldrush of the 1850s, was on the verge of being made even richer by the new transcontinental railway. It was a good place for a skilled, energetic jobbing photographer and Muybridge prospered. Some of his pictures were reportage, showing war, native tribes, new buildings as they rose in San Francisco, coffee cultivation in South America, all the lighthouses on the California coast (an official commission) and engineering works on the new railway. Other Californian subjects show more aesthetic ambition and were widely and profitably published in albums. The most striking are views of the bare granite cliffs, deep valleys, still lakes, pine-covered slopes and high waterfalls of Yosemite. There was a lively market for images of the Californian landscape, and some of Muybridge’s were taken on very large plates (photographs in those days were nearly all contact prints), outdoing the competition in size at least. His images are a little less ‘painterly’ than some: the compositions are less conventional and, literally, more daring – he often chose exposed outcrops and high vantage points. He is less likely than some of his contemporaries to be identified as a precursor of photographers such as Ansel Adams, who in the 20th century took advantage of filters and panchromatic film to produce images of Yosemite in which bare, sculptural rock faces appear as pale masses against dark skies. By such means landscape photography became a more calculated art, but you could argue that the technical limitations of earlier prints bring one closer to the reality of wilderness.

If his landscape work (much of it more interesting as topography than art) were all he had done, Muybridge wouldn’t have been given such an extensive display at Tate Britain. It was Stanford who wanted to know whether a horse, trotting or galloping, ever has all four feet off the ground, and it is for his sequential pictures, of animals and later of people in motion, that Muybridge is celebrated. He was working as a technician rather than an artist, using banks of cameras as an analytic tool. The objectivity that photography had promised was here realised. The set-up was, of course, arranged – the horse trotted past on its allotted track, the woman climbed the stairs provided – but it was the mechanical operation of the camera that uncovered details of movement the eye cannot resolve. To do this, Muybridge made good use of Californian light, as well as Californian money (Stanford was determined to get an answer; a substantial bet may have been involved): cameras were bought from England and fast shutters developed locally.

A row of cameras, triggered by the animal itself (later by electric switches), in light bright enough to allow very short exposures (down to a 1000th of a second) captured a sequence of pictures close enough in time for the path taken by each limb between one shot and the next to be established. When the pictures were examined Stanford was proved right: there was a point in the horse’s stride when all four feet were off the ground. That he treated Muybridge as a technician rather than a creative contributor became clear when he published a book using the results under his own name. Muybridge sued and lost.

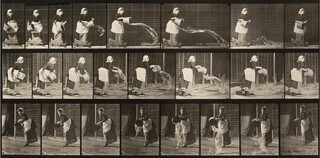

Muybridge analysed an amazing range of gaits and contortions. Horses gallop, jump and canter, a buffalo trots, dogs lope, men and women walk, do gymnastics, wrestle, throw buckets of water. Blacksmiths strike iron. The photographer himself, nearly 50, naked and bearded, swings a pick. Later images were made while he was employed by the University of Pennsylvania, although that connection ended when he was unable to supply the teaching materials (moving pictures of the gaits associated with various conditions) they had expected. By mounting his sequences on discs that turned while images were projected onto a screen (he called the device a ‘zoopraxiscope’), the fragment of time dissected by the photographic process could be reassembled and made to repeat itself time after time. (Although Muybridge was not central to the development of cinema, the zoopraxiscope did demonstrate effectively a cinema-like running-together of photographic images.)

As a scientific procedure Muybridge’s work was from the first challenged by single-lens pictures that superimposed multiple images on a single plate, and later by sequential cinematic images taken at greater and greater speed. But his effect on painters was far-reaching. Some, like Meissonnier, who went to great lengths to confirm the accuracy of his own work, and Eakins, whose perspective studies were of a Uccello-like rigour, saw it as a revelation. No one who painted or sculpted a horse could ignore the paradigm shift that had taken Stubbs’s rocking-horse gallopers and gathered their legs into altogether new arrangements. As for the attitudes of Muybridge’s moving human figures, they were evidence of things the conventions of art – perhaps even inherent habits of seeing – had hidden. Post-Muybridge Degas’s dancing girls at rest might look inelegant, but they couldn’t be accused of not being true to life. Where earlier painters used Muybridge’s photographs to get the detail of their paintings right, Francis Bacon, drawn to their impersonal, objective quality, made subjects of, for example, Muybridge’s wrestlers. Meissonnier wanted a crib; Bacon had found a source.

The frozen moment has now become a commonplace. In Muybridge’s early photographs of waterfalls, taken over several seconds, the drops and flurries of water register as misty extrusions, very like the ectoplasm in spiritualist pictures. Even Leonardo’s drawings of water catch only the generalities of turbulent flow. When men and women throw water in Muybridge’s later pictures, it is caught in sharp, disintegrating arcs. Today the back pages of the morning papers carry photographs of footballers caught in poses that would seem quite implausible if the slicing up of the moving world into millisecond images had not become part of what we know. We still need technology, though, to make it possible.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.