Blythe House, a late Victorian pile close to Olympia, was built to house the Post Office Savings Bank. It’s now the V&A’s working store for its art and design collections. Tiled corridors and rooms where thousands worked (male and female clerks carefully segregated) are now filled with racks and lined with cupboards. Through glass doors you glimpse recognisable objects: guns, tiles, pots, table lamps – and nameless parcels. Some walls are lined with plaster casts. I saw only one curatorial huddle, but men and women do work here. All that is not being conserved or packed is ordered, labelled, docketed. A visit was possible because until 27 June Blythe House, which usually allows no visitors, is open to anyone who has reserved a place on a tour. Parties of up to seven people are taken to the roof by lift and led back down by way of stairs and corridors to work spaces filled with packing cases and rolls of plastic wrap, to store-rooms with banks of rolling shelving and, finally, to a coal bunker.

This access was arranged so that the building could become the site of The Concise Dictionary of Dress, a collaboration between the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips and the exhibition maker Judith Clark. The project was commissioned by Artangel, which has had a hand in other transformative events – for example, Francis Alÿs’s CCTV footage of a fox exploring the National Portrait Gallery at night.

On your descent through floors of things sleeping the sleep of the unexhibited, you pause 11 times. Your guide hands you a card with a word and a definition. For example:

PRETENTIOUS

1

Something pretending to be something that it is.

2

An experiment in excess; excess on trial.

3

The courting and claiming of ridicule; making embarrassment the solution and not the problem.

4

Exposing a certain blandness in the environment, a needless uniformity in the situation; a revealing of assumptions; a reinforcing of conventions.

5

Full of misgiving.

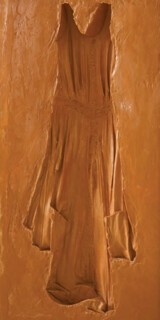

Each card is illuminated, if not exactly illustrated, by an installation, a display that may include garments, old and new, photographs, objects from the V&A and other collections, and things made for the exhibition: wax ‘casts’ of clothes, a grid of diamond-shaped cubby-holes that contain a glove and porcelain figurines of hunchbacks, a wonderfully skilful piece of embroidery extrapolated from a William Morris design. A translucent resin cast of a woman looks out over London from the roof.

There is also a book, also called The Concise Dictionary of Dress (Violette, £25). Sixteen of its pages are set out like fancier versions of the cards from the exhibition; five do not have associated installations. The headwords are: armoured, brash, comfortable, conformist, creased, diaphanous, essential, fashionable, loose, measured, plain, pretentious, provocative, revealing, sharp, tight. The definition pages are interspersed among photographs by Norbert Schoerner of the installations and the rooms and corridors of Blythe House. There are also Clark’s answers to questions from colleagues and eight pages of catalogue. The book begins with an essay on dictionaries by Phillips. Words, meanings, and how people think and feel about dress are the central issue.

The experience of walking through the building and attending to the objects and definitions encourages guessing, dreaming and fantasising. The principles of museum display (logical order, well-lit presentation) and the apparatus for imparting information (labels, printed catalogues, audio guides) that discourage these reactions are absent. On the other hand, the juxtapositions and definitions on offer are the curators’ own, so the guesses and dreams they invite are circumscribed. It would be bliss to be allowed to open up, hang up, pack and unpack the things hidden around you. The managed skimming of the bounty on offer here can be as much a tease as a revelation. Just how is it all intended to work? Phillips says ‘a dictionary of language and installation plays off information against evocation, getting it right against the gorgeous eccentricity of personal association.’

It is clear, of course, that the definition cards have nothing to do with ‘getting it right’ in the ordinary factual sense. Phillips excludes that: ‘There can be no obvious dictionary for clothes, fashionable or otherwise, no straightforward reference book.’ He excludes therefore anything like The Thames and Hudson Dictionary of Fashion and Fashion Designers (‘every important designer from 1840 up to the present day … fashion terms, garment and accessory styles, technical processes and every kind of fabric … international in scope’ etc), which is just the kind of book you would turn to if, reaching the eight pages at the end of the Concise Dictionary (where you do get to know who made things, what they are made of, who owned them and how old they are), you needed help with, say, ‘powerwoven Dupion silk fabric’. But that dictionary won’t have an entry for ‘pretentious’ – or for ‘provocative’ or ‘conformist’. So is ‘getting it right’ finding the constellation of definitions that describe our personal, perhaps unconsidered but nonetheless deep responses to dress and being dressed? Are the installations and definitions here hybrid routes to self-knowledge?

When Phillips has it that ‘the words and the objects in the exhibition exhibit each other, show each other off,’ he seems also to be saying that the objects and definitions will educate us, not in facts, but in attending to the experience of dress and of being dressed. But that is not quite what happens. When the curatorial role in setting up an exhibition takes on a quasi-creative character (it has much in common with collage-making), when it seems to aspire to the charm of a Joseph Cornell box or the disturbing presence of Duchamp’s farewell peepshow (Etant donnés), it must be judged, as those hermetic works are, for itself. But in that case the surrounding, hidden riches of Blythe House, and the listing, explaining and so forth in the book’s final eight pages, should be no more necessary to the force of the work than it would be to know the origin of a scrap of newsprint in a Picasso collage. The problem here is that some of the collaged scraps are works of high craft, more interesting in themselves than the didactic spirit that seems to have governed their selection.

The context – Blythe House – illustrates the oppressive superfluity that comes to haunt collections. What in an individual can be an obsession that teeters towards madness is institutionalised in a museum. Of all the objects orphaned in collections, clothes and musical instruments are the most troubling. Tools can look to be at rest after a working life. Paintings and sculpture never had any life other than being looked at. Pots and furniture don’t demand to be filled or sat on for their virtues to be appreciated. Dead beetles still glisten. Archives and books can be accessed. But a shift or a shirt needs a body, a violin or a flute a player. The first of the questions put to Clark was ‘Does one need a body to bring a garment to life and why?’ Her answer is ‘yes’, but she goes on to say that her concern is not bringing to life (‘if by this we mean the re-enactment of history, or the proximity to its original use’). Instead, she says: ‘I use dress to talk about other things.’ That may be the problem.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.