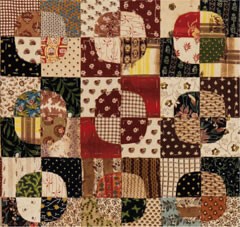

Those who use repeat patterns – weavers, tile-makers, quilt-makers, wallpaper printers – rub up against the territory of mathematicians. In Symmetry, Marcus du Sautoy describes how, dodging among the tourists, he found all of the 17 possible symmetries of the plane on tiled surfaces in the Alhambra. Quite a number of symmetries can be spotted in the quilts in the new V&A exhibition (Quilts 1700-2010, until 4 July). But while the Alhambra tiles are in plain colours the quilts enliven a primary tessellated geometry with patterned patches. Each patch may have its own symmetrical repeats and their position sets up (or breaks) other patterns. A further layer is added to the symmetries if the piece is also quilted – stitched to a backing through a layer of padding. In plain fabric quilts (a good part of the exhibition is given over to them) the lines of stitching alone can be complicated.

In traditional domestic patchwork a more or less predictable geometry is enlivened with quotations from everyday life – a bit of an old dress, a scrap of uniform, grandmother’s curtains, lengths of ribbon – whose meaning will only be fully appreciated by the maker. Sometimes mill off-cuts, tailors’ remnants and other sources of newly woven fabric were used, but more often, and more interestingly, quilts drew on the unpredictable contents of the ragbag. A layer of words and pictures, appliquéd or embroidered, were sometimes added to educate, amuse, admonish, or record names and dates. The impression left by the part of the exhibition given over to patchworks like these is of rich, desirable, sometimes eccentric outcomes made possible by frugal ways with material and an abundance of amateur time (or cheap labour). On the other hand, it is possible to exaggerate the domestic connection. While it was always a home craft, quilt-making was sometimes a source of income and there is some evidence in the V&A collection of workshop production in London, Exeter and Canterbury. In the 20th century there were partially successful moves to revive quilt-making as a rural craft on a commercial basis. Plain quilts with traditional stitched patterns – they fitted remarkably well with the Art Deco interiors – were much praised when provided by Rural Industries Bureau quilters in 1932 for a renovated wing in Claridges. Recently quilting’s emancipation from amateur craftwork to gallery art has often resulted in sewn pieces that are more commentaries on the nature and status of women’s work than covers to snuggle under. Some are made of materials (paper, plastic) that are not even inviting to the touch.

Those whose awareness of quilts as art objects came in the 1970s by way of exhibitions of American 19th and 20th-century pieces won’t find much here to match the geometric designs in a few colours (red and white were particularly effective) of American examples. Those could be read as prefiguring the abstract painting of the 1950s and 1960s; the exhibition Abstract Design in American Quilts at the Whitney Museum in New York in 1971, organised by the collector Jonathan Holstein, seemed to slot the quilt into the history of Modernism. It wasn’t, so far as I know, possible to show that quilts influenced Jasper Johns, say, in the way African sculpture influenced European art in the early 1900s, but the formal congruence was striking.

Strongly patterned quilts were made in Britain too – particularly in Wales and the North where, one may suppose, printed cottons and patterned silks were less common. There are Welsh examples in the exhibition – and a handsome quilt in broad red and white stripes from Northumberland. But the bias of what is on show at the V&A is towards intricacy. A principal reason for this is the past policy of the museum. Many of the early pieces in the exhibition are from the V&A’s own collection and were acquired when the emphasis was on the bits of old fabrics rather than the pattern of the quilt.

Documentation is often fragmentary and not always trustworthy. Take a coverlet, probably made by Elisabeth Chapman around 1829, perhaps to celebrate her marriage. Tradition had it that the paper shapes the patchwork pieces were tacked onto before being sewn together were love letters. That proved to be false: when examined they turned out to be ‘a typical range of papers available in the middle-class home: ledger books, children’s copy books, advertisements, newspapers and receipts’. Any attempt to date patchworks suffers not just from family myths, but from the fact that there is no saying how long fabric or paper had been lying in a drawer.

Craft work is, by its nature, repetitive. When a potter, quilter or blacksmith begins to make unique pieces rather than runs of objects they tend to be seen as artists or amateurs rather than professional craftsmen. The older, amateur quilts in the exhibition are pretty but repetitive, and often less interesting in themselves than in what they tell us about the lives of the people who made them. A quilt is evidence of much time spent quietly and usefully. ‘A man cannot hem a pocket-handkerchief,’ a ‘lady of quality’ said to Samuel Johnson one day, ‘and so he runs mad, and torments his family and friends.’ The anecdote is recounted by Mrs Thrale. Johnson, it appears, was much impressed and, in Mrs Thrale’s telling, ‘when one acquaintance grew troublesome, and another unhealthy,’ he would in turn say: ‘a man cannot hem a pocket-handkerchief.’ But men could at least be calmed down by quilting. In the large cover or hanging made (or perhaps acquired) by Francis Brayley, who served as a private soldier in India from 1864 to 1877, the patches of wool fabric are stitched into lines as regimented as any on a parade ground. The army, worried at the danger posed by bored troops, promoted all sorts of handwork to fill their time: this militaristic hanging is very likely a result of that drive.

Quilt-making has also mitigated the boredom of prisoners. During the sea voyage to Van Diemen’s Land in 1841 the women of the convict ship HMS Rajah made a large patchwork coverlet with materials supplied by the British Ladies Society for the Reformation of Female Prisoners. The thanks embroidered on it may seem too humble for modern taste. The messages on the hexagons of the quilt commissioned for the V&A from the all-male quilting group at Wandsworth Prison are more challenging, displaying ‘a clear conversation with both the history of the British prison system and contemporary discourses on authority’.

But a quilt as commentary is not new. The patchwork made in his spare time in the decade between 1842 and 1852 by James Williams, a Welsh tailor, shows Cain and Abel, Noah and his ark and no end of animals. It also applauds modern engineering with representations of the Menai suspension bridge and the Cefn viaduct. There are patriotic and religious quilts which would elevate your dreams with biblical quotations or disturb them with a profile of the troublesome Queen Caroline. Among the recent items in the exhibition, meaning becomes a – perhaps the – dominant theme. Susan Stockwell’s A Chinese Dream shows a world map machine-stitched together from Chinese banknotes. A ‘crazy’ patchwork – crazy as in crazy paving – called Memoriam and made of steel wire wool and transparent plastic by Michelle Walker recalls the way her mother, who died of Alzheimer’s, would obsessively twist her hair. And there is Tracey Emin’s bed (To Meet My Past), piled and hung and quilted and draped with patchwork and embroidered words, which is really very close, in its mix of pattern, message and found stuff, to Elisabeth Chapman’s quilt.

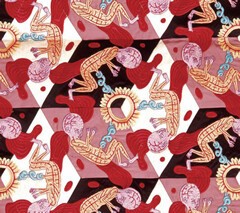

These quilts-as-art sometimes deny the virtues of soft, pretty materials. A deeper difference between professional art and amateur craft lies in the way they address time. The slow handkerchief-hemming business of traditional patchwork, its use of scraps, both of time and material, if necessary taking years to finish a coverlet or hanging, rebukes waste of both hours and stuffs. I thought Right to Life, Grayson Perry’s handsome and disturbing velvet quilt, embroidered with rotating foetuses (he has spoken of ‘the bed as a site of danger: the place traditionally associated with both birth and death’), must have gone against the trend and involved many hours of stitching. In fact the embroidery was stitched by a computer-controlled machine.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.