A shrine may be personal, private, even secret. It is a place where votive objects (models of limbs, figures, charms) are collected, where sacrifices are made, where curious memorials, fading flowers, dishes of food, are left. Here gods are propitiated, saints appealed to, spirits appeased. The aesthetic is one of unplanned accumulation. Churches and temples, on the other hand, are monumental, their ceremonies public: their architecture and decoration make sense. The shrine can be intensely personal, amateur, and is often made – sometimes with obsessive care – from whatever comes to hand. Churches and their art are professionally assembled from recognised materials.

The early rooms in the Chris Ofili exhibition (ends 16 May) have shrine-like and church-like aspects. The neutralising ambience of the museum, which makes altarpieces into paintings and fetishes into sculpture, here aestheticises the rankness of content in Ofili’s earlier work: the penis as clown, the poses from girlie magazines, the caricature faces, and the balls of elephant dung that bulge from time to time from the pictures’ surfaces. In the later work the references are less gleeful. It is as though the museum has tamed a wild child. Ofili now produces regular, gallery art: oil paintings even.

The stuff the objects and paintings are made of and their subject matter follow parallel trajectories. Shithead (1993) is a bolus of elephant dung transformed into a head by the addition of hair and teeth. It is made from ‘human teeth, artist’s hair, polyester resin and copper wire on elephant dung’. In the early paintings the use of materials is similarly eclectic: The Adoration of Captain Shit and the Legend of the Black Stars (1998) is made from ‘oil, acrylic, polyester resin, paper collage, glitter, map pins and elephant dung’. But Dance in Shadow (2008-9) is simply in oil on linen.

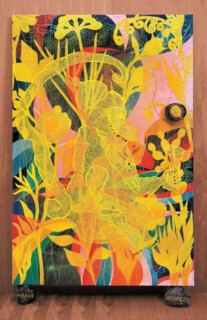

The most remarkable achievement in the early work is the group of 13 paintings called The Upper Room, one of which is shown here. Ofili, brought up a Catholic, finds both inspiration and opportunities for transgression in biblical subjects. Each canvas shows a monkey holding a chalice that has been drawn over a background of leaves and flowers, which itself overlies a field of brilliantly coloured swirls and segments. Each monkey outline is filled in with small, shiny bead-like dots arranged in concentric curves like the seeds on a sunflower head. The flowers and leaves are outlined with the same dots. Each monkey is a different colour; its toe and fingernails picked out in blue, yellow and red.

The brightness, intricacy and elaboration of all this, the sheer amount of work that has gone into dotting and layering, demonstrate a shrine-maker’s concentration of effort. The oddity of it, the obscure connection to its ostensible subject matter, makes the meaning of the pictures of The Upper Room private. The way they are displayed, on the other hand, is church-like and public. They aren’t hung on walls but, like other paintings Ofili did at the time, are shown leaning against them; in this case against the walls of a wood-lined chapel-like space. Six six-footers on each side, a gold eight-footer facing you as you come in, all of them supported by balls of dung. The effect is splendidly rich (all that layering and dotting), calculated, purposeful – and bizarre. The pictures suggest, as tapestries and embroideries do, that the methods and materials have both disciplined and encouraged invention, that care has gone into them, along with the shrine-maker’s delight in assembling materials. The space in which they are displayed, the processional approach via the corridor that runs along one side, the implications of the title and the formal arrangement of the works all suggest a ceremonial chapel. Or a safe room created to exclude the museum’s demythologising radiation.

Something of the same atmosphere is achieved in a room of later, blue pictures: Blue Riders, Iscariot Blues, Strangers from Paradise, Blue Stag (All Fours). The colour is so dark that reading them is difficult, reproducing them even more so; it is as though you were looking at the world through the dark blue filter of the cinema’s ‘day for night’. The struggle to see just what’s going on – to know why musicians are playing on a platform beside the gibbet from which a naked Iscariot hangs, or who the mounted strangers are – will not be resolved. You are held, drawn into a mystery for which you can expect no explanation.

In these, and in other paintings produced since Ofili moved to Trinidad in 2005, the figures are no longer set against a ground, as the monkeys are against their glowing, intricately patterned field. Now everything – leaves, bodies, abstract elements – is in the same register. You even find him using devices that are familiar from the image bank of 20th-century art. Here and there – in the black/yellow/ orange/purple colour scheme of The Raising of Lazarus, for example – I hear an Art Deco echo; Christmas Eve (Palms) grew out of a 1963 photograph by Malick Sidibé of a couple dancing but has Miró-like passages. In Confession (Lady Chancellor) a long, purple, red-headed nude with scarlet nails reaches for a drink tendered by a black hand emerging from a white cuff that enters the picture at the top left-hand corner. Her feet and toes stretch out like roots to meet Art Nouveau at its most vegetative. Kitaj often used the same diagonal emphasis and similar colours and distortions. It is not a question of influences or borrowings, just a sense that Ofili has come to make his contribution to a long-running party.

There are drawings and watercolours too. Many of the latter, in groups collectively entitled Afromuses or Afronudes, are both repetitive and graphically striking. The colour is radiant (so much so that I wonder, anxiously, whether they were done with Dr Martin’s Radiant Concentrated Watercolour Inks – produced in ‘extremely concentrated form to achieve the greatest possible brilliance and radiant tones’ but ‘NOT lightproof’). However achieved, the dark browns and blacks of skin and hair and the glittering details of red lips and red vaginas in the nudes are as far away as you can get from the hundred shades of grey, brown and green with which English watercolourists caught this island climate.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.