Sculpture was once strong on monuments and memorials. Now it’s a puzzle to know what to do with an empty plinth. To embellish a building (not just label it) hardly makes sense when walls are made of glass. In parks and open spaces new pieces, often not much liked, are vulnerable. A historical account of English sculpture, until it gets well into the 20th century, will deal mostly with makers of monuments, memorials, tombs, statues of the great, portrait busts and decoration for buildings. But thereafter the creators of public sculpture are no longer part of the mainstream, their work likely to be resented. The exceptions tend to be makers of large, simple pieces.

Yet Henry Moore, whose work epitomised modern art for a generation, never gave up on public sculpture. Early on he was a member of the last generation able to contribute substantial stone sculptures to the fabric of new stone buildings: his modernity, like that of Epstein and Gill, was apparent not just in his sculptures’ style but in the fact that they were carved directly, not copied mechanically from plaster originals. The look was new, the methods ancient. Later he was much taken with putting sculpture in landscape and the best of the pieces that have found the kinds of site he wanted for them concentrate the visual character of the countryside and have something of the presence of megalithic monuments.

Later still, after the war, with the title ‘the world’s greatest living sculptor’ visited upon him, he was commissioned to fill sites at home and abroad with pieces like the reclining figure in front of the Unesco building in Paris and the family groups in the Harlow and Stevenage New Towns. They were modern but not aggressive. They fulfilled, and were intended to fulfil, old monumental roles. The human body, however abbreviated or distorted, was still the primary subject. Moore’s figures didn’t challenge with anatomical explicitness, as Epstein’s early work did, and they could still stand for abstract generalities – ‘motherhood’, ‘family’, ‘humanity’. His large abstract sculptures in bronze – echoing the shapes of flesh, bone or worn stones and pebbles – were imposing but comfortably biomorphic. Fiercer readings of, for example, the jagged multi-part reclining figures as victims of bombs or bayonets were possible but not obvious. Many pieces were, in a quite traditional way, beautiful physical objects. The eye takes pleasure in the surfaces of stone, wood and bronze as one imagines the hand of the maker must have done.

The argument of the Moore exhibition at Tate Britain (until 8 August), much of it work from the 1930s and 1940s, is that Moore the benign humanist and craftsman obscures a more complex sculptural personality. The exhibition sets out to show that there has been a tendency to forget the degree to which his work is strange, even anxious; troubled about sex, violence and the dark side of humanity.

It isn’t straightforwardly a matter of development through time. The last room at the Tate contains four of the six large reclining female figures he carved from elmwood between 1936 and 1978. The gallery itself is bright and made to seem more so by the paleness of the smooth, sometimes polished wood. The differences between the figures are considerable – smooth curves give way to more angular transitions – yet what they have in common outweighs this: small heads, holes that transform the solid tree trunk into heavy legs and arms which also read as a landscape of mounds and hollows. The sense this gives that earth and woman are one is emphasised by the way the wood is polished and gouged – the grain follows the form as contours follow the slope of a hill – and led to analyses such as David Sylvester’s of the 1945-46 Reclining Figure: ‘the sacrificed and resurrected god of a fertility rite … at once skeletal and alive, prone in burial and flowering into new life’. The carvings in this room provide a formidable example of sustained invention around a common theme, carried out over four decades. The large scale, which feels arbitrary in Moore’s late bronzes, here announces the size of the trees from which the figures were carved: the scale of the material becomes part of the work. It is sculptures like these – along with some on related themes – family, mother and child, standing figures – that made Moore’s work instantly recognisable, even popular.

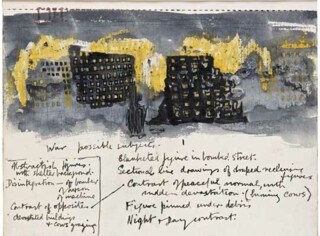

The real breakthrough to a wide public owed less to sculpture, however, than to the drawings he made during the war. Working as a war artist among crowds sheltering in the London Underground and alongside miners in Yorkshire pits, he gathered material for drawings that dignified the work and the lives of the population at large. The technique was sculptural, in the sense that the shapes of bodies and blankets are described by lines that follow contours. Graphically the approach is typical of the curved hatchings of the engraver rather than the linear outlines and shading of the draughtsman. The lines circle limbs, building shapes with stone-like solidity as pen or crayon feels its way over every visible surface. Ordinary Londoners become solemn and weighty, like Masaccio saints. The drawings are impressive, a response to being at war, not to the actual waging of it, nor to the bloodiest suffering. After the war, with Hiroshima, the opening of the concentration camps and the ongoing conflicts of the 1950s, Moore embraced harsher realities in bronzes of falling warriors (some missing legs and arms, some holding shields), and in sculptures of women, seated or reclining, whose bodies are swollen or distorted in ways that have none of the earth-mother softness of the elmwood figures.

It’s interesting to turn back to the earlier work with what came later in mind. Carvings from the 1920s have the chunky solidity of Egyptian hard stone carving, though there are all sorts of other echoes – African, Etruscan, South American. Through the veil of influences that freed sculpture from the need to cling to the look of things, the rhythms of a classical tradition can be felt. The splendid Reclining Figure from Leeds carries memories of classical sculpture, while the figure in Girl with Clasped Hands in alabaster turns her head just enough to avoid the frontality of tribal carvings and early Greek sculpture.

In the section labelled ‘Modernism’ there are pieces in which references to the human figure are obscure or disappear altogether, but even these will have holes, notches and indentations that suggest signs for eye, nipple, mouth and so on. It is in this section that we find some evidence for the depth and strangeness the exhibition wants to inject into blander views of Moore’s work. There are no easy readings. Sylvester tells us that Three Points (1939-40), in which the pointed ends of a fat, sharp-ended banana shape reach round nearly to touch one another, meeting a third spike that rises from the centre of the curve, was inspired by the School of Fontainebleau double portrait of Gabrielle d’Estrées and her sister in the bathtub. ‘The fastidious pinching of Gabrielle’s nipple between her sister’s pointed forefinger and thumb gave Moore the idea of a sculpture in which three points would converge.’ It is an uncomfortable piece, and now I have some sense of why that is.

Moore said that African sculpture was dominated by sex and religion. The influence of African and other traditions on his art was great, and ignorance of its meaning in a tribal context may have enhanced the freedom it brought. Yet it is the sense one has when faced with ancient or exotic things that there is something beyond what can be grasped by mere inspection, if only some priest or shaman could give the correct interpretations, that makes the obscure impressive. We don’t necessarily need to know what things mean, but we do like to think they mean something: we want to know what Stonehenge was for.

No modern sculpture is embedded in systems of belief of that sort. With Moore you must look to your own responses for explanations of what you see and feel. What you learn about his own relation to them helps only a little. The carvings are wonderful.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.