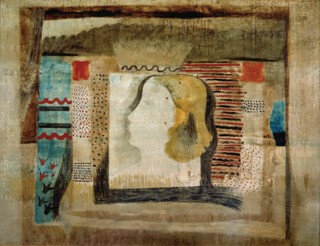

Surfaces in pale earth colours – brown, grey and buff – scraped and rescraped until they look like a wall ready for papering. Backgrounds overlaid with strong accents in brown and black or with patches of red, blue and green, bright as flags on a yacht. The whole articulated by hard pencil lines, some ruled, some making simple curves and circles. All of these things can be found both in Ben Nicholson’s landscapes and still lifes and in later abstract or near abstract works. The sharp lines aren’t there in the early faux-naïf landscapes made in the late 1920s – the firm mono-line draughtsmanship took over later – but the colour schemes are already established.

The other dominant strand in Nicholson’s work consists of white or near white reliefs. Words like ‘purity’ and ‘balance’ stick to descriptions of them like a burr to a sock. It was these constructions of overlapping circles and rectangles that he finally came to concentrate on – their very elegance and poise can make one hanker for old scrubbed earthy textures. The Nicholson exhibition in the De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill (until 4 January; it will go on to Tate St Ives) has plenty of scrubbed earth. It isn’t an alternative view, so much as one which, by including pieces that can’t be placed on the direct path to pure form, puts Nicholson in the company of other English artists who dipped into abstraction and then out again (as John Piper did) or who abandoned impressionistic realism of a traditional sort for it (as Victor Pasmore did). None of them in doing this lost a craftsmanlike pleasure in things well and carefully made. That may be why it is almost as easy to relate the look of both Nicholson’s and Pasmore’s paintings to pots made in England (the texture of those by Bernard Leach or Michael Cardew, the sgraffito on those by Lucie Rie) as to the work of European artists such as Mondrian and Gabo whose presence in England was an obvious source of inspiration. The naive paintings Alfred Wallis made of Cornish harbours and ships offered access to the unsophisticated directness that Parisian artists had found some decades before in African sculpture.

The Bexhill exhibition does show white reliefs from the 1930s, but it cuts off at 1958, when Nicholson moved to Switzerland. It has, as well as early landscapes, some done during the war – when that was all dealers were interested in. In both drawings and paintings the subject matter is the same set of English hills, worn down like old bones, vernacular buildings, ships, bare trees, and faded interiors of the kind seemingly much more conservative painters turned to – such as Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious. Art of a given time and place comes to us with a sense of the rooms in which it was made. In England in the years between the wars that often meant a cottage in the country or a house in a village or market town. Nicholson lived both in Cumbria and in Cornwall and the forced frugality of the 1930s and 1940s artistic interior seems to relate to the aesthetic of many of the earlier paintings, just as the late reliefs relate to the look of the modern, white house on Lake Maggiore that he moved to in 1961.

August 1956 (Val d’Orcia), the big still life that won the Guggenheim International Painting Prize in 1956, has white shapes – a table and table legs – over which curved black and red-brown slices of colour suggest bottles, dishes and a coffee pot. The background is scratched and scrubbed; his mother’s kitchen table, he said, was the influence to look for, not his rejection of the fluency of his father’s oil paint. Yet one reads this table top with a pleasure that is not entirely unlike the pleasure one gets from William Nicholson’s jugs and plates.

The pictures on show at Bexhill make Nicholson seem a very English painter, a practitioner of the restraint and charm that English art in the 1960s was keen to distance itself from, but which – in Hockney’s drawings, for example – keeps breaking through. The minimalism of the reliefs that gave Nicholson a claim to the title of England’s most thorough Modernist was not, like the Russian work it bears some resemblance to, revolutionary in any political sense. He did play his part in a revolution of a kind, but what at first sight may have seemed aggressively new now has a very English old-world charm.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.