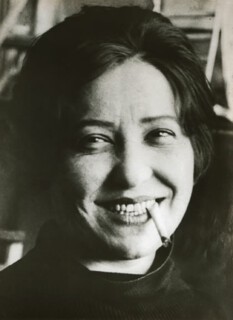

When Alexander Rodchenko began taking photographs in 1924 he was in his early thirties and already known as a painter of severe abstracts and maker of constructions and photomontages. He produced many of his most memorable photographs during his first few years with a camera: his wife, Varvara Stepanova, smiling with a cigarette gripped between her teeth; his mother, holding folded spectacles up to one eye; and several portraits of Mayakovsky. (One Mayakovsky must be earlier than others as his head is not shaved; according to a note about her father by his daughter, Rodchenko himself started the shaving trend in 1920. Other members of LEF – Left Front of Art – later followed suit.)

Judging by Alexander Rodchenko: Revolution in Photography, a new exhibition of his work (at the Hayward Gallery until 27 April), Rodchenko made fewer memorable pictures of individuals as time went by. Instead, the camera’s ability literally to give a fresh angle on things, the aspect of photography that he emphasises in a text of 1934 where he looks forward to ‘compositions that surpass the imagination of painters in daring’, delighted him. He was particularly intrigued by views from high up looking down and from low down looking up. Photographs from 1933 show Georgy Petrusov lying on the ground to take pictures of his wife; Rodchenko must have been crouching when, in 1930, he made close-up, foreshortened portraits of young Pioneers. In the repertory of poses photographers have invented or borrowed, heads seen from below against the sky tend to stand for things like ‘hope’, ‘striving’ and ‘looking to a new horizon’. Photographs taken from above, on the other hand, make patterns out of human activity and embed individuals in groups: crowds weave past each other, bands march, workers eat in the factory kitchen. Looking up at a modern building or fire escape led the eye towards a distant vanishing point; hold the camera at an angle and the stolid horizon becomes an active diagonal.

Newly available miniature cameras encouraged this kind of thing. The Leica was both a tool and a symbol – it is seen here along with a pen and notebook on the cover of the magazine Zhurnalist – and in the hands of photographers it is as significant a professional attribute as the rifles shouldered by marching soldiers in other photographs. One of Rodchenko’s two or three most famous images is Girl with a Leica of 1934. The photographer’s camera has been tilted so that the bench on which the girl sits runs from corner to corner. A grille of some sort casts a grid of shadows over her face, her white dress, the bench and the boardwalk in front of her. In photographs like this – and in others of architecture, glassware, industrial machinery, even of gymnasts, swimmers and tall trees – rhythm and symmetry are abstracted from subject matter. The graphic artist’s pursuit of structure is dominant.

This concentration on pattern-making suggests that the accusation of ‘bourgeois formalism’ levelled at Rodchenko by those who wanted socially uplifting imagery was – as far as ‘formalism’ went – fair enough. In other countries photographers have angered their contemporaries more often by pointing their cameras at the wrong people and places than by abstraction. From August Sander’s portraits of German types, labelled degenerate by the Nazis, to Robert Frank’s photographs of a sadder, rougher USA than the picture magazines showed, to Richard Avedon’s pictures of Westerners who were odder and stranger physically, and maybe mentally, than local pride allowed to be possible, and Diane Arbus’s freakish finds in the park, the complaints have been ‘too cruel’ or ‘we’ (who ‘we’ might be is not clear) ‘don’t look like that’. Rodchenko’s situation was such that even had he wished to uncover the truth about rural poverty, say, or human misery in the Gulag, it would have been impossible. The closest he came to it was with a commission to produce a picture story on the making of the White Sea-Baltic Canal. The photographs he took were edited by the authorities and he wasn’t allowed to take away with him any that hadn’t been approved. Once you know that the crowds of navvies digging and carting clay are made up of forced labourers and political prisoners, something of the misery of their situation comes home to you. Rodchenko said that he had ‘photographed in a simple way, not thinking about formalism’.

The results, widely published, were propaganda, but American contemporaries were making propaganda too – photographs of dams built by the TVA, for example. Walker Evans’s photographs for the Farm Security Administration – in their way, quite as formal as Rodchenko’s – also carried messages that are now subject to sceptical scrutiny. Rodchenko’s work was made with more editorial oversight than that of his American contemporaries but he had more control over its presentation than they did. It is in the posters, magazine and book layouts and covers designed by himself and his wife that his aesthetic intentions are seen most clearly. These graphic items, exhibited here along with photomontages from the early 1920s, provide a necessary context for his photographs.

The exhibition, organised by the Moscow House of Photography Museum, is particularly well served by the book they have published to accompany it. In both book and exhibition the photographs are described as ‘vintage’ – indicating that they were printed around the time the pictures were taken – but some illustrations were either made from prints other than those in the exhibition or are miracles of electronic enhancement. For example, in the 1927 portrait of the poet Nikolai Aseyev the fine detail of cloth and skin is clearly visible only in the illustration. Portfolios of Rodchenko photographs printed from the original negatives by his grandson are available at around £1000 a print; it would have been interesting to see some of these. When early Modern artefacts that depend on perfect surfaces for their effect show the effects of time, when the chrome chips, the white paint yellows and the plywood is scratched, it is poignant in a way the patination of older things is not. But were Rodchenko working today I imagine he would have given up scissors and paste and turned to Photoshop. Although old photographic prints have qualities that cannot be re-created in new ones (materials change and negatives age), Rodchenko, who incorporated what are now among his most famous photographs into collaged graphics, would I think have been happy to have us see them rejuvenated.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.