A new exhibition, Temptation in Eden: Lucas Cranach’s Adam and Eve, runs at the Courtauld Institute of Art until 23 September. It consists of five paintings: Cupid Complaining to Venus, Apollo and Diana, A Faun and His Family with a Slain Lion, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and the Courtauld’s own Adam and Eve. There are also some wonderful drawings and pertinent prints.

Many galleries have only one Cranach, and you can see why they might not want more. Much is repetitive. All five pictures in the exhibition have the sky that fades from vibrant blue to pale yellow; three have a rocky hill, distant buildings and a reflecting lake; all include dark evergreen foliage against which naked figures stand out. And the figures – above all the pale young women, sometimes Eve, sometimes Venus, sometimes another deity – are standard too. Cranach Girl is an ideal female type, more interesting and variable than, say, Gibson Girl or Varga Girl, but still a clone. It took time, however, for her to blanch and slim to her final form. A plumper Eve of 1508-10 derives from Dürer’s Eve of 1507: a Renaissance woman, her shape instructed by the calculated ratios with which Dürer tried to tame and trap beauty. In Dürer’s wonderful engraving of Hercules at the Crossroads (it is in the exhibition), the volumes and curves of the naked figure of Pleasure, described in controlled hatched lines, give an answer in flesh to an equation in geometry. Cranach’s Eve is a clumsy version of Dürer’s, but the conventions he settled on in later pictures (those in the exhibition come from the mid-1520s) showed that there was more than one way to pursue ideal beauty. His anatomy and geometry are still weak, but he seems to get one closer than Dürer does to the reality of nakedness. Although Cranach Girl tends to have a standard body – medieval in its proportions, the breasts smaller and the limbs less shapely than those built from classical sources – she has more than one expression. But even when she invites your attention she allures without being welcoming. Her general character is confirmed in Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, where the serpent, shown like a mermaid with a woman’s torso is, tail apart, Eve’s twin. She is not to be trusted. In the Courtauld Adam and Eve, Adam stands bemused, scratching his head, as he looks at Eve over the bitten apple: ‘What have you got us into?’ She doesn’t return the look, but her satisfied half-smile suggests that she is pleased to find herself in control.

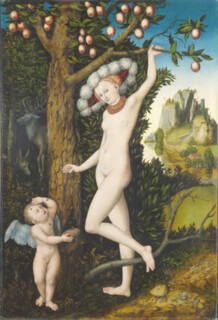

Venus seems to invite more perverse and dangerous adventures. Randy Newman has a song that begins: ‘Baby take off your coat real slow.’ The verse ends (shoes and dress gone) with a three-line refrain:

You can leave your hat on

You can leave your hat on

You can leave your hat on

That is what Venus has done in Cupid Complaining to Venus. Her hat is large, round and trimmed with feathers. As in the song, what’s left on makes you more aware of what has been taken off. As a result, the Venus is provocative in a way figures in the four other pictures, all of which show men and women wearing nothing at all, are not. Titian’s Venuses, that are more or less contemporary, lie soft, languid and pampered on couches, sometimes accompanied by an organ player or a less obstreperous Cupid. (Cranach’s Cupid has stolen a honeycomb and bees are stinging him, just as his arrows sting lovers.) Cranach’s Venus stands in the wild wood, more like the lady in the ballad who abducts True Thomas from a goddess. Faint, downy wisps of pubic hair suggest that she is a distant ancestress of Balthus’s nymphets, yet body and face are ageless rather than young.

Much of the catalogue (Paul Holberton, £20) is devoted to discussion of Cranach’s contemporaries and what they might have made of it all. He lived in Wittenberg from 1505 through to his death in 1553 and was court painter to the electors of Saxony. He was close to members of the faculty of the university – Philip Melanchthon was one. Cupid Complaining to Venus relates to a Greek verse Melanchthon used as the basis for Latin moralities. Contemporaries would have registered that the roebuck, which laps water in the foreground of Adam and Eve, was famously faithful and monogamous. Classical/biblical analogies – between Venus and Eve, for example – would not have escaped them.

All five paintings in the exhibition are, in a sense, animal pictures. Stag, boar, lion, roebuck, sheep, horse, stork, quail and heron gather in Adam and Eve. A stag and a donkey lurk in the forest behind Venus. Diana uses a stag as a sofa. Blood trickles from the nose and mouth of the lion the faun seems to have clubbed to death and an extensive menagerie gathers in Eden on the meadow where God instructs his new creations, Adam and Eve, about life in the garden. Naked humans seen in these contexts have their animal nature confirmed.

Cranach knew animals well and at first hand. He was not great on anatomical structure, but he was a fine observer of surface detail and animal behaviour. With a dead beast in front of him he could produce sheets of a refinement that matches the precision of Dürer’s plant and animal studies. His drawing of a hind shows perfectly the way its coat goes from rough to smooth as it follows the contours of body and neck. On the back of that sheet are much sketchier drawings of living deer seen from various angles, grazing, fighting and rutting. If they were not done from life they are evidence of a finely retentive memory. There is an excellent drawing done in this looser style of wild boar being attacked by dogs. In another, of a pair of partridges strung up on a hook, death has allowed time for details of soft breast feathers, wings and scaly legs to be attended to.

These drawings were templates a painter could use as reference, although the painter was not always Cranach himself. He was over 80 when he died and for much of his life ran a highly efficient and productive workshop. There are 27 extant versions of the complaining Venus, more than fifty of Adam and Eve and many portraits of Martin Luther. Luther was a close friend, but that did not stand in the way of Cranach doing portraits of Canon Albrecht of Brandenburg, an anti-Lutheran Catholic dignitary who liked to be shown as St Jerome in his study. Cranach’s winged-serpent monogram on a picture was a trademark and guarantee of quality rather than an indication that the picture was all his own work. Yet different versions are not replicas; each has been redrawn from scratch, not copied stroke by stroke. Freshness of attack and lively detail, not just of animals but of plants as well, explain the difficulty scholars have in arriving at decisions about which pictures and parts of pictures are from Cranach’s own hand.

The prime entertainment of Cranach’s royal patrons was hunting. Pictures of the hunt – represented here by a woodcut – were an important part of his work. In the woodcut you can see a stag driven into the water by hounds, another with a hound hanging from its antler, a boar caught by the leg, huntsmen winding their cross-bows and charging with spears, noble riders coming and going. It was not all done from imagination. In an encomium on Cranach, the humanist Christoph Scheurl reported that Cranach accompanied Elector Frederick on hunting expeditions and brought with him a panel on which to make visual notes about the chase.

The exhibition is a model of its kind. In a small compass it illuminates the intellectual sources of Cranach’s work and the meanings that can be extracted from it. And it gives a context to what is beyond explanation: the mannered, amusing, perverse charm of his curious invented world.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.