With every blockbuster, the Guggenheim prompts suspicion: ‘How did it get the loot, and to what end?’ The current mega-show, Russia! Nine Hundred Years of Masterworks and Master Collections, on until 11 January, is drawn mostly from the Tretyakov Gallery and the Hermitage, and it doesn’t seem too paranoid to wonder about the geopolitics in play. ‘Realised under the patronage of Vladimir Putin, president of the Russian Federation’, the catalogue says, Russia! is ‘the most comprehensive survey since the end of the Cold War’.* This reads like code for an attempt to rebrand the country for a post-Communist era under the aegis of the present autocrat.

Such packaging is in keeping with the substance of the show, which is all about image and patronage, patrimony and politics. We glimpse several refashionings of Russia, and art and history are entangled at each turn, with a number of storylines to tease out: narratives of art, indigenous and foreign; of an empire confident in its expansion and anxious about its competitors; of contradictions exposed in 19th-century art and painted over in 20th-century work. In effect, Jacques Grange, the French designer of the show, has turned the Guggenheim into a ‘Russian Ark’. In his 2002 film of that title, Alexander Sokhurov used the conceit of a promenade through the Hermitage, shot in one long take, to evoke the complicated history of old Russia. At the Guggenheim we spiral up through nine centuries of culture; ‘documents of civilisation’ dominate, but a few ‘documents of barbarism’ stick out.

Broken into nine sections, the show begins strongly with more than twenty icons, most of which date from the 15th century. Many are hung in a dim gallery to evoke the ‘iconostasis’, a screen on which five tiers of such images might appear all at once, unique to the Russian Orthodox Church. Although the museum celebrates the icons as ‘art’, that category is anachronistic: they were made, mostly anonymously, in monastery workshops, and fidelity to precedent, not innovation, was the point (all icons of Christ were thought to derive directly from the legendary portrait by St Luke or the miraculous impression left on Veronica’s veil). Yet transformation is evident, especially with Andrei Rublev, who in the early 1400s did for Russian painting what Giotto did for Italian painting a hundred years before – he opened up the flat surface to embodied space. Already, histories of art and power intersect. On display is the celebrated Virgin of Vladimir, brought to the Kiev region after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 as part of a mission to save the heritage of Christianity from the infidel. Yet Moscow also aspired to be the ‘Third Rome’, so it appropriated the Virgin in turn.

This use of art to legitimate a claim to power is the leitmotif of the show. It is at work in the next section, where the reigns of Peter and Catherine the Great are represented by holdings of European masters such as Bronzino, Rubens, Van Dyck, Murillo, Poussin, Claude, Watteau and Chardin. A great gap exists between ‘The Age of Icons’ and ‘Imperial Collections’ – was there no Renaissance or Baroque in Russia? There was, but they are registered in architecture (the Kremlin is Renaissance and the Hermitage Baroque), furniture, armour, costume and porcelain, and the focus on painting throughout the show rules out most of this material. Nonetheless, the 18th-century section includes enough grim court portraits and broad city vistas to convey the politics of the time. If Muscovy vied with Ukraine in ‘The Age of Icons’, St Petersburg competes with Moscow during this period, the former associated with European sophistication on the rise, the latter with Slavic Church identity in decline. The portraits point to the divergent allegiances in play: many Petersburgians appear in European dress and many Muscovites in kaftans, and the landscapes suggest the extension of the empire – north to the Baltic under Peter, south to the Black Sea under Catherine.

The long 19th century is given two sections. The first, ‘The Coming of Age of Russian Art’, highlights Romantic and Realist paintings, as if artistic maturation meant continued Europeanisation. Yet native subjects remain strong, and genre scenes of peasant life appear for the first time. Landscape also undergoes a powerful Russification: big paintings of golden harvests, vast snowfields, the fabled forests, steppes, rivers and seas – the combination is distinctively Russian. The second section focuses on such social developments as the rise of city merchants (the new patrons of art), the emergence of the intelligentsia, the freeing of the serfs and the formation of artists like ‘the Wanderers’ (who wandered away from the academies to exhibit independently). Ilya Repin, the best-known of this group, is represented by an astute portrait of the merchant Sergei Tretyakov (whose collection is the basis of the gallery named after him); it captures an inward subjectivity not found in any previous image of saint, tsarina or soldier here. Another Repin on view is the famous Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870-73), in which 11 bedraggled men tow a ship as if it were the Cross. Typical of the Wanderers, the painting mixes critique with affirmation: ‘Russia is ruled despotically,’ it seems to say, ‘but this tragedy makes us great.’ The show-stopper is Defeated: Service for the Dead (1878-79), a Vasily Vereschagin landscape of corpses attended by two figures, a priest and an officer, who seem implicated in the deaths they mourn. Both paintings glow with the gold of icons: again the subtext is Russia made holy by sacrifice. And both are broad as well: a further encounter with a Russian spatial sublime that first overwhelms and then bolsters the native ego. Yet their illustrational moralism is also close to kitsch, and the formulas of Socialist Realism are not far away.

Some merchants identified with artists and writers against the autocrats, and the finest fruits of this support were the foreign collections of the Moscow merchants Ivan Morozov and Sergei Shchukin: apart from the Stein salon in Paris, the best sampling of advanced painting of this time was probably in Moscow, and it served as a crucial prompt to the avant-garde of Malevich, Tatlin and others. Because Modernism came late to the Russian Empire, it was fast and furious: all the greats of this generation seem to pass through a quick catechism of Fauvism, Futurism, Cubism and Abstraction. This culmination is announced by Malevich’s c.1930 Black Square (one of four) and Rodchenko’s Triptych: Pure Red Colour, Pure Yellow Colour, Pure Blue Colour (1921): the first sought to transcend bourgeois painting mystically, the second to declare it dead politically. Another casualty of the curatorial emphasis on painting is the great Constructivist episode that accompanied such abstraction: we are given only one Tatlin relief and one Stenberg construction, and no posters, agitprop work, magazines, book covers or films. Lissitzky, the great ambassador to European Modernists, is scarce, and Gabo non-existent.

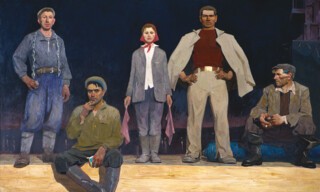

A smart presentation of Socialist Realist painting helps to compensate for this omission. To an extent our stereotypical view of this stereotypical art is confirmed. Its signal combination of photographic realism and typological idealism (noble farmer, worker, soldier, leader) is exemplified by Isaak Brodsky, whose V.I. Lenin in the Smolny (1930) is a superb specimen of the style; and there are some Stalinist howlers as well: An Unforgettable Meeting (1936-37), which groups Party associates around Uncle Joe greeting a young female comrade, is unforgettably bad. Yet there are surprises too, such as the stark, almost Neue Sachlichkeit austerity achieved by Alexander Deineka in Defence of Petrograd (1927), as well as the quasi-Impressionist vitality of New Moscow (1937) by Yuri Pimenov. Although Impressionism was dismissed by Socialist-Realist diktat, its idiom, which once conveyed the new Paris of capitalism, is deployed here to celebrate the new Moscow of Stalinism.

Socialist Realism has problems with the purges and the war: it’s not easy to pretty up the deaths of 27 million people, but some painters tried. After the Khrushchev thaw the mood darkens in paintings of grim workers at power stations and furtive intellectuals in cafés. A dissident art emerges, and there follows the now-familiar ‘unofficial art’ of Sots artists such as Komar & Melamid and Eric Bulatov, as well as the Conceptual installations of Ilya Kabakov and others. Some of this work – for example, a painting that charts the planned life of the Soviet citizen – still has bite; much of it, however, is as inane as art anywhere in the Free World.

Why is a show of nine centuries of Russian masterpieces housed in a museum founded to advance ‘Non-Objective Art’? Abstraction here is entirely overwhelmed, along with the revolution in art and society it heralded. Such seems to be the view from the Kremlin now: a Russian Ark of greatness, past, Putin and future. Titles followed by exclamation marks call up associations with toothpaste adverts and tour packages, and in some respects this is what Russia! is: an inspirational trip to a Potemkin village made of art.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.