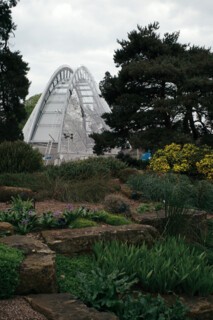

Anew Alpine House is due to open later this year in the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. But you can already get a good idea of how it will look. Its footprint is small but the curved profile of its glass walls stands surprisingly high on the garden horizon. Think of it as a miniature version of the Wembley arch, the Gherkin, the London Eye – other landmarks which have bubbled up on the London horizon in recent years. The architects, Wilkinson Eyre, designed the Gateshead Millennium Bridge (also curvy) and are now working on, among other things, the King’s Waterfront Centre in Liverpool. A recent exhibition in a blacked out subterranean space at the Wapping Hydraulic Power Station at Wapping Wall – itself an impressive piece of plant, dear to industrial archaeologists – gave an insight into their work. There you can see a double display: Reflections (an installation, prepared for the 2004 Venice Architecture Biennale by the architects and the sculptor Bill Pye) and Destinations – which includes models, projections and moving pictures. Here, in the common visual currency of building proposals, computer-generated visuals of astonishing verisimilitude are slipped into photographs of the sites the new structures will occupy, blurring the distinction between what has been imagined and what has been built. This is engineering in images, where methods and materials matter less than dreams and fantasies. These days we can make anything we can imagine, and the magic is in the manipulations.

The new Alpine House will be the third to be built in the last hundred years. The first dates from 1887 and is essentially an overgrown greenhouse: a pitched roof with staging on either side of the building and a path down the middle. It is now given over to bonsai. The shell of the second Alpine House, which looked a bit like a very small version of the Louvre pyramid, was built from commercial greenhouse components in 1981. The new building, which replaces it, is an example of Hi-Tech Picturesque: an ornament-free, geometrically complex design in a style computers have made feasible. Window walls and metal cladding can now match the curves of a nautilus shell or the membrane of a bat’s wing. Large areas are covered by glass panes butted up at the edges or overlapping, fixed together to resemble those ancient Chinese funeral-suits made of hundreds of plaques of jade. The most developed versions of the style are now often characterised by complex clasps, hinges and bearings – an aesthetic prefigured in the cladding and cables and anchoring points of Frei Otto’s suspended structures.

Styles come into their own when they meet appropriate problems. A plant house which will be a local landmark but must also be able to simulate exotic climates is an ideal task for Wilkinson Eyre’s particular version of hi-tech, just as the needs of the 1852 Palm House (Decimus Burton, ironwork by Richard Turner) were well served by advanced cast-iron technology. In both cases, aesthetic predilections are appropriate to practical needs. The larger, more stolid Temperate House (mainly 1859-62), also by Burton, is larger than the Palm House but visually less thrilling. Similarly, the factory aesthetic of the exterior of the Princess of Wales Conservatory speaks of the complex control systems inside. The new Alpine House, which sets out to solve a simpler functional problem, will come closer to making architectural poetry.

Plant houses must both exclude local weather and imitate foreign climates: arid deserts, Amazonian jungle, tundra, alpine meadow. They have to be proof against different assaults inside and out. The ultimate in controlled habitat-imitation is an artificially lit, ventilated and humidified growing room: the kind of structure that is set up crudely and illicitly by cannabis growers. In Kew, a garden as well as a research facility, such total control is limited to a few behind-the-scenes propagation rooms. The contrast between one climate and another, which hits you when you pass through the doors of the tropical houses, is also, to a degree, expressed in the look of the buildings.

In most of the Kew houses much of the planting is permanent and the plants themselves are often substantial. Once you are inside, vegetation masks everything apart from the glazing bars. In the Palm House their curves echo those of palm fronds; in the Princess of Wales Conservatory you are aware of them only if you choose to look up from the beds, ponds and banks of planting. In the Alpine House it will be rather different. Alpines tend to be small and have brief flowering seasons. They are brought in from cold frames season by season, and put on display as they come into bloom. The structure will never be lost among foliage. The only aesthetic anxiety one has is that the plants may be overwhelmed by the architecture, as drawings can be by heavy gilt frames.

The architecture will be dominant, and some aspects of the building look like architecture for architecture’s sake. But they have practical justifications: this isn’t self-indulgence. For example, the height, which seems disproportionate to the floor area, provides the large enclosed volume necessary for the proper control of air temperature: small greenhouses overheat very quickly. One problem with the 1981 building, apart from noise – ventilators cranked open and shut – was temperature control.

The plant houses at Kew record changes in the relationship between plants and people. Kew’s botanical role came quite late. Unlike the ancient European botanical gardens it does not have its origins in 17th-century medical science. When botanical exploration and commercial plant hunting brought specimens to Europe that required more delicate nurturing, houses to contain them followed. One was specially built in 1852 to house the giant Amazonian water lily. Now the collection and cultivation of what is rare or endangered goes along with attention to ecosystems. Group plantings are more common than single plants in pots: that is how the palms were first set out and how the alpines used to be displayed.

Kew is a research establishment, but there’s little direct evidence of it. The Alpine House fulfils another function: it is an appurtenance of a pleasure ground. As many of the plants will be brought on like circus performers at their moment of flowering and then sent back behind the scenes, it may seem irrelevant to the work which ensures the survival of rare species. But the work goes on because we collectively think it worthwhile. One function of the Alpine House, and its ultimate justification, is to advertise that work and display it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.