The tenth and last room of the Joseph Beuys exhibition at Tate Modern (until 2 May) contains Economic Values, a piece from 1980. It consists of metal shelving stacked with household goods in bottles, packets and bags, all bought in what was then the GDR. They have, as Beuys intended, begun to disintegrate. The walls of the room are, as he requested, hung with ‘19th-century paintings in gold frames from the host museum’. Their dates fall within the lifetime of Karl Marx. The bags and packets had a ‘simplicity and authenticity’ which reminded Beuys of his childhood. They tell us that ‘we do not need all that we are meant to buy today to satisfy profit-based capitalism.’ The pictures point the finger at bourgeois taste. The whole is a symbolic tableau to which the categories of illustration or didactic window display are as appropriate as that of art. Think of magazine spreads which show the difference between what the average family eats in a year in country A and country B, or showcases near airport customs posts containing a jumble of prohibited imports – a stuffed baby crocodile, fireworks, forbidden fruits, seeds.

In another sort of museum, some of Beuys’s work would become material evidence – like the icons in Soviet museums of religious superstition. But a gallery exhibition, with its sponsors and donors, is itself an aspect of the ‘profit-based private capitalism’ that Economic Values addresses. Inevitably, the politics and polemics become a bit cracked and dusty, like the packages on the shelves; slogan-like constructions become artworks whose qualities as objects take on an autonomous life. An art of protest and self-examination is incorporated into the culture of excess it criticises.

One way to respond to these displays is to give them the same status as the masks and effigies displayed in a museum of anthropology. Many of those were made to be discarded – even destroyed – when the rites in which they were used were over. Like Beuys’s work, they often involve materials that are fragile and liable to decay. Like his work, they have meanings and mythical references that must be explained.

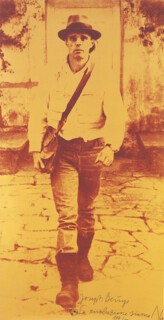

Beuys’s myths are personal and political, not tribal. The most important of the personal myths – it is no longer, I gather, to be taken as true – tells how, after his plane crashed in the Crimea during the Second World War, he was rescued by Tartars who coated his body with animal fat and wrapped him in felt.

Political stories and arguments underlie another kind of work, the real events he set up and participated in. These ‘Actions’ were by their nature ephemeral; they could be recorded, but not possessed. The most famous of them, I Like America and America Likes Me, was carried out in 1974 (it was recorded; a video is on view in the exhibition). Beuys flew to America, had himself unloaded from his plane wrapped in felt and transferred by ambulance to a gallery. He was put in a room with a coyote. Fifty new copies of the Wall Street Journal were delivered each day; the coyote urinated on them. Beuys, sometimes wrapped in a felt blanket, sometimes making gestures with his walking stick, always wearing gloves, his trademark felt hat and fisherman’s vest, had an uneasy relationship with the animal, which showed a range of behaviour from aggressive to canine-companionable. The Action was resolved after some days when Beuys, having set foot on no American soil except the floor of his gallery/cage, was rewrapped and delivered back to the airport. In this work, Beuys explained, he was addressing contemporary scandals – the Vietnam War – and ancient ones: the treatment of native peoples to whom the coyote was sacred.

The sculptural pieces on display at Tate Modern are sometimes monumental (The End of the 20th Century of 1983-85, which consists of large, rough-hewn columns of basalt scattered over the gallery floor) and sometimes funny: The Pack (1969) is a battered VW bus from which sleds, each with a roll of felt, a lump of fat and a torch strapped to it, stream out in ordered rows, as though leashed together like a dog team. But maybe I shouldn’t be amused; Beuys said: ‘In a state of emergency the Volkswagen bus is of limited usefulness, and more direct and primitive means must be taken to ensure survival.’

The flavour of the exhibits as a whole is didactic. The trickster-tease twitches at the curtains that hide from us the oddity of making and using art. For a moment or two he makes us wonder, uneasily, what we think we are about when we wander around galleries – and, at the same time, why we don’t think more about ourselves and our planet.

Beuys’s work is European: its essentially moral force arises from his own situation and the situation of Europe after the Second World War. American work which uses the same materials and methods is not haunted, as his is, by the sense that something has gone so wrong with a culture that the old categories of picture and sculpture are exhausted or contaminated. American art of the 1950s expected big galleries and big rooms and quite quickly found rich patrons to cherish it; but even when the influence of Pollock or Rauschenberg can be documented in contemporary European careers in art, American confidence is cancelled out by the experience of war. The modernity of Beuys and of Jannis Kounellis – a collection of Kounellis’s work, covering his whole career, is to be seen until 20 March at Modern Art Oxford – shares an ascetic frugality of means, dull colour and, even when the work is monumental in scale, a retreat from monumental rhetoric.

Born in Greece in 1936, but working in Italy, Kounellis was a protagonist of the minimal set-ups and common-object manipulations of Arte Povera. Where Beuys was overtly political, Kounellis, who said that the task was ‘to tell the tale of the enormous drama of loss’, can be read in terms which are primarily aesthetic; it is significant that he has, over the years, made a number of installations which, unlike Beuys’s, don’t refer to society or politics, but confront the traditional displays and spaces of churches and museums.

In Oxford, all the kicks Kounellis offers are visual. If there is meaning of another sort to be extracted from the metal shelf with an egg on it, from the bowl of water with the knife resting in it, even from the great forest of tilted, bolted girders which rest on a forest floor of oriental carpets and fall away from you like tree trunks blown over by a great wind, it still isn’t meaning you hunger for. One’s first impression is that this work is much more concerned than Beuys’s with how it looks. Beuys, by contrast, calls for explanation. Tate Modern supplies a pamphlet for visitors to the exhibition which is a model of its kind and offers just the enlightening information you want. I have never before seen people spend so much time reading about what they are looking at. Kounellis has made things that invite attention in a way that would make commentary an intrusion. His room of steel plates, resting on chairs, with regular arrays of lumps of coal fastened onto them with wires; the column with the steel rope fastened round it; the toy engine which endlessly circles another column; the big, black puddles of paint crossed with girders; the sewing machine suspended from a rod: all leave you with the sense that you have seen something significant, but not at all worried that you don’t exactly know what its significance might be. The old coal sacks, the unspun cotton which presses out from the corners of containing walls, allow the kind of charmed puzzlement which is now part of the visually educated tourist’s response to the world. That they will come back from abroad with a picture of shoes by a door or of an oddly painted wall, where their grandparents would have been looking for the nearest thing nature could offer to a picturesque landscape, is due in part to art like this. The message fades, the style remains.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.