The first part of The Triumph of Painting – there will be two more – is at the Saatchi Gallery in County Hall until 5 June. It isn’t exactly a triumph. Resignation is in the air, as though the force behind twenty years of Saatchi exhibitions is on the wane. In those exhibitions things became famous without necessarily being seen. People felt they knew the tent, the bed, the shark, the fly-infested cow’s head, whether they made it to the gallery or not. The concept was more telling than the reality. When you saw the pieces in an exhibition (and very large numbers of us did) they turned out to be more banal than you expected. It was like being drawn by curiosity to the site of a train crash or the scene of a murder and finding the reality more melancholy and less dramatic than imagination had promised, a bit icky but not mind-blowing. The opposite is generally true of painting; if you haven’t seen it in the flesh you will miss a lot of what it is about.

Their presentation and reception often implied that the pieces which made headlines for Saatchi’s earlier collections were late entrants in the long anecdotal history of artistic transgression. In those tales the transgressor is vindicated. From Caravaggio’s St Matthew (who was said to be too peasant-like) through Ruskin on Whistler (‘I never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face’) to Dickens on Millais’s Christ (a ‘hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy in a bed-gown’) and on to Duchamp’s urinal, the artists are shown having the last laugh. If they do not – if their work, when it has lost its power to shock, turns out to have little else going for it – the anecdote ceases to be told. Félicien Rops may now have his own museum in Namur, but his name no longer means much. In such cases the anger of the affronted can seem more alive than the work that aroused it.

It’s easy to overstate both the extent to which transgression dominated Saatchi’s collections and the extent to which his collecting over the last twenty years nudged English art in a direction determined by his taste for it. On the other hand, it’s clear that the boundary-testing elements determined the bulk of the response to the work. Without Saatchi-supported transgressions, modern British art would not have had even half the attention it has. If nothing else, his activities prove that a private collector can be single-minded, extravagant, decisive (and, if you like, manipulative and ruthless) in a way that a public patron cannot. Critics and historians talk and judge; collectors commit. It’s unlikely to be the Tate trustees who carve an alternative modern canon from the totality of what is made, cast, performed, photographed and painted in Britain.

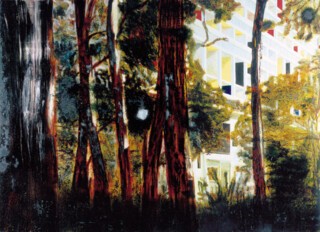

In one way, most of the artists shown in this exhibition sustain Saatchi’s reputation as a connoisseur of transgression. Marlene Dumas’s paintings – a row of naked boys; a little girl with her clothes pulled over her head – fit with her own statement that ‘my best works are erotic displays of mental confusions (with intrusions of irrelevant information),’ and with the handout’s claim that ‘Dumas makes paintings with no concept of the taboo. Racism, sexuality, religion, motherhood and childhood are all presented with chilling honesty.’ Jörg Immendorff’s canvases ‘are fraught with imagery, a proverbial, and often literal theatre of decadence’. Hermann Nitsch’s taboo images and performances using ‘animal carcases, entrails and blood in a ritualistic way … put him out of favour with the authorities’. Luc Tuymans has drawn on the Holocaust and the politics of the Belgian Congo for subject matter in work which addresses ‘the challenge of the inadequacy and “belatedness” of painting’. Martin Kippenberger died young eight years ago. He managed to be doubly transgressive when he went Warhol and hired a company which specialised in painting cinema posters to produce pictures including a number of self-portraits and ‘completely clichéd images culled from existing sources (including a hardcore pornographic picture of a couple mutually masturbating)’. That picture is in the exhibition. Only in Peter Doig’s dreamlike pictures of canoes on lakes, snow scenes and modern buildings seen through trees is there no hint of cultural transgression.

Paint, however, imposes its own non-transgressive charm. Dumas’s brushstrokes soften the actuality and perversity of the photographs her work is based on, as does the Wayne Thibaudish thickness of the paint in Kippenberger’s commissioned pictures. Nitsch’s Six Day Play, a ‘product of a re-enactment of the story of creation’ which was ‘by far his most decadent execution’, fits easily, seen on the wall, with the high-art aspirations of American action painting.

When you look through the big Triumph of Painting picture-book, which reproduces the works in the next two parts as well as those in the current one, the only transgressions in sight in what is coming up are aesthetic.* Quotations – from commercial kitsch – and brushwork that makes something out of de Kooning’s way with bodies cause you to wonder what you are supposed to make of the references. Most of the work to come seems to be a mild, if confusing, mélange which brings to mind the very imperfect skills and very high ambitions of a good degree show. Among them, however, are things I look forward to seeing for real. Wilhelm Sasnal’s black aeroplanes fly towards you out of the blue – just as the planes do when you look down the flightpath at Heathrow: I am curious to know what they look like on the wall.

But nothing here makes me think that painting is making a triumphant return. In one way, it has no need to. It has been going on anyway: a return would be a return to a particular kind of public attention rather than an increase in the activity itself. The most you can say is that such renewed attention might make it become once again the highest and most rewarding ambition a picture-maker could have. Although no one, including Tuymans himself, has solved the problem of ‘belatedness’, the itch to paint has not been cured; the affliction may be chronic.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.