This year Zaha Hadid won the Pritzker Prize. The award was founded by Jay Pritzker who owned the Hyatt hotel chain – not that the winners of the prize have produced much that looks at all like the buildings which underwrite it. It is given annually to an architect who has, among other things, ‘produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment’. In the dream days of architectural Modernism, those contributions would have included a grand social vision of planned cities drawing distant inspiration from nice places (Italian hill towns, 18th-century spas) which had escaped the vivid, dismal chaos brought about by modern transport and industry. That chaos is now more often acknowledged than challenged by architects. The self-generated complexity of cities strains the infrastructure of roads, pipes and cables, stretches the language of building regulation and planning law, and throws up petition-signing protest groups at the drop of a computer-generated perspective. It is a situation that promotes sociological analysis and technical, economic and political design decisions. Bespoke architecture is a prestigious garnish on an urban environment in which most new building is off the peg. Most new buildings are smart, clean and nicely detailed. But they do not thrill. The architects of the scattering of showcase projects which manage to get built – new art galleries, the odd parliament building or library – assume a duty, not just a licence, to challenge norms. Designers who can do this will not necessarily have cut their teeth on run-of-the-mill buildings.

The Pritzker Prize juries (this year’s was headed by Lord Rothschild and included Frank Gehry, who won the prize in 1989) have, over the years, chosen a significant number of winners (Gehry, Rem Koolhaas and now Hadid) whose reputations, at the time of the award, depended to a great extent on small buildings or on their contributions to a parallel universe of competition entries and imaginary projects. Hadid, in particular, has been famous for winning prizes for buildings – a nightclub in Hong Kong, the Cardiff Opera House – which didn’t get built.

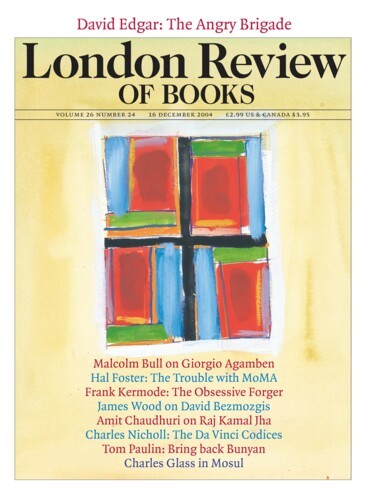

A number of her designs have now entered the real world (a tram shelter, a garden exhibition building, a fire station, a ski-jump, an arts centre) and a whole lot more, many quite substantial, are underway. Even so, her architectural talent reached maturity without her or anyone else having much experience of how her ideas would work as buildings. In this situation the images used to explain and present an unbuilt project are important. Hadid has shown us what her buildings could be like by making, among other things, paintings. They provide some of the illustrations for a suite of four books on her work, each a different and appropriate shape – big for photographs, small for text, all ingeniously slotted into a red plastic box – which has just been published.*

In a small room at the Gilbert Collection in Somerset House, until 16 January, there is an exhibition of several of these paintings, while a big screen runs video clips and digital animations of built and unbuilt work. The paintings are highly finished, with a neat, anonymous surface. In texture and size they look, at first glance, like very close-grained, asymmetric versions of one of Bridget Riley’s prismatically divided, coloured abstracts. But these images do not read as flat surfaces; they are accounts of a three-dimensional world. The field is divided into shards and lozenges: the faceted forms of Cubist painting combine with the angled lines and rectangles of the Russian Suprematists. You identify, quite quickly, what must be a cluster of downtown skyscrapers. Another flat pattern resolves itself into a contoured slope. You can imagine the pictures translated into models, but can see that they are stronger in two dimensions than they would be in three.

The style of architectural graphics tells you both what an unbuilt structure will look like and how you will be expected to look at it. Nineteenth-century perspectives suggested you look at it as a picture. Twentieth-century diagrammatics asked that you analyse it. The dark hatched skies and sharp pen lines in Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s perspectives borrow graphic conventions which were, so far as I know, the invention of Aubrey Beardsley. The drawings come to mind when you look at the buildings; away from the buildings the drawings take precedence, just as a cartoonist’s version of a face usurps the real one.

Hadid’s graphics remind me of the steep perspectives and vertiginous sweep of illustrations in science fiction comics. In both cases, structures (a spaceship, a walkway) float above the ground. In more recent computer renderings from her office, the resemblance is all the greater. The graphics echo but do not necessarily depict the buildings they relate to. The grids, lozenges, hockey-stick curves and pierced membranes, and the walls, enclosures, stairs and walkways they hint at, can’t be related to an ordinary set of plans and elevations – there aren’t many on offer in these books. Where there are photographs of finished or unfinished buildings they are often of details – proof, as it were, that the experience the graphics promise is available on the ground. The most substantial of the completed buildings is the Lois and Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati. There are photographs of the exterior which make it possible to grasp the look of the whole, but while you are offered interior views of stairs and circulation spaces it is almost impossible to work out what the exhibition spaces are like. (There is an indication of the response the building gets in a notice on a window beside one curved wall-member forbidding skateboarding, climbing and cycling.)

A new architectural style is, for obvious reasons, often first tried out on a small building. One with few evident functional demands is ideal. William Chambers gave as full a trial run of his kind of correct Classicism as you could wish for when he began his designs for the casino at Marino in Ireland. An exhibition building – Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion is one example – can be pure architecture. Hadid’s fire station in the grounds of the Vitra furniture factory is now a chair museum; it is disappointing to know that the red fire engines in the photograph are no longer in place, but they were inhabiting an architecture so pure that any function could seem a distraction from its sharp prisms of concrete and sheets of glass.

There are limits to what can be built. Some are set by the strength and availability of materials, others by the skills and labour available. One which has only become apparent now that it has disappeared is the limit set by what can be represented on a flat surface. Rectangles come naturally when you draw with a T-square on a drawing board. On a computer screen it is much easier to draw curves and bubbles, to have planes interpenetrate at odd angles and slide around. Stresses and loads can be calculated, the result translated into working drawings, and photographically-real renderings produced without intolerable labour. If you wish you can take a mouse and track through spaces or fly over buildings. These freedoms have natural outcomes – in the increasingly complex roofs of stadiums, for example. The rectangular room, however, filled with rectangular furniture, rectangular books, even rectangular monitors and screens still has, for practical as well as cultural reasons, so firm a grip on us that only in very special buildings (Hadid’s ski-jump is one beautiful instance), or in pavilions where the wall is functionally a tent, is it possible to cut or smooth its corners without awkward results.

In science fiction, however, curved walls, blobby furniture, organic bulges and invaginations are the rule. Non-rectilinear functionality drove the last right angle out of the saloon car (not to mention the small boat) decades ago. Hadid’s work is acclimatising us to a wider non-rectilinear world. If her buildings feel as the graphics and photographs suggest they do, she has shown the way to a new kind of Mannerism – one that finally releases modern architecture from the hegemony of post and beam as the Mannerism of the 17th century released architects from the hegemony of the rectilinear plan. There are of course older examples – Corbusier’s Ronchamp, Scharoun’s Berlin Philharmonic Hall – which didn’t result in a revolution. But Hadid, Gehry et al now have engineers to turn to who can make rounding the corner a much less onerous affair than it once was. Whether our rectilinear souls will succumb to curves and sharps in unexceptional buildings remains to be seen.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.