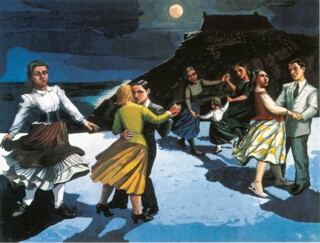

There is a display of Paula Rego’s work at Tate Britain until 2 January. Her pictures invite, demand even, that you attend to what they are about as well as to how they look. They are – if one allows that families, like countries, have struggles and conflicts – political narratives. They make you ask what is going on, and lead you to answers which go beyond a verbal reply. If words alone would do, why make pictures?

Sometimes images can save the facts underlying feelings of outrage from being blurred by rhetoric. In 1834 Daumier made a famous lithograph of a slumped corpse, the victim of a royalist massacre in the rue Transnonain. The man, in nightshirt and nightcap, his splayed legs towards you, lies on a sheet pulled from the bed. His head lolls against it. Daumier caricatured kings, judges and lawyers. He made little plays out of the absurdities of ordinary people. The image of the rue Transnonain victim is more a document. To look at it is painful. This is not a cartoonist’s symbolic protest or a martyred saint. It is a murdered man.

You have to go that far back to find good comparisons for the pictures Paula Rego made in response to the news that a referendum in Portugal had failed to sanction the legalisation of abortion. These big pastels made in the late 1990s show women in bare rooms, lying on a bed, sitting over a bucket, some in poses very like that of Daumier’s dead man. Like Daumier, Rego is unsentimental. You don’t feel pity for the women she draws so much as anger that such things happen. Her victims are strong.

Everything she has done – the surreal collages which were her first notable achievement, the graffiti-like drawings, the paintings, more and more realistic until they finally become direct accounts of posed models – engages you as narrative. What is going on? you ask. Why? What next? Most of them are about the experience of girls and women, about the exercise of power and its abuse, and about subterranean aspects of human relationships. Balthus gave us the male view of pubescent girls trapped in closed rooms; Rego seems to be offering their obverse. Her women will escape. Balthus made the best illustrations for Wuthering Heights that I know of, but Rego’s lithographic riffs on Jane Eyre are stranger and go much deeper.

The early pictures look very different from the late ones, but even those furthest removed from plain views of things require narrative readings. In many of them, as in folk tales, parts are played by animals. There is a strip cartoon version of Aida in which rabbits, dogs, a baboon, a monkey and a crocodile have bigger roles than ancient Egyptians. Another set of pictures tells a story about Red Monkey, who offers Bear a poisoned dove; Wife (who is human) and cuts off Red Monkey’s tail, and so on. Animals, Rego says in an interview with Fiona Bradley in her 2002 study of the artist, were what made it possible to tell these stories. ‘With people it would have looked totally absurd.’ Animals have always been important in Rego’s pictures. The near abstract, surrealist collage at the Tate, Stray Dogs (The Dogs of Barcelona), of 1965, was a response to a news item which described the poisoning of strays by the city authorities. In a set of pictures of girl and dog painted in the 1980s the dogs are equal players, not decorative attributes. Why is one dog being shaved? Why is a girl lifting up her skirt to a dog? What will be tipped down the throats of dogs whose jaws are being forced open? In the pictures at the Tate you find animals which seem to have an active part in stories that don’t demand their presence. In The Policeman’s Daughter a cat looks out of the window. An ominous little black pig fills a corner in The Maids, a premonition of the murders to come. In Rego’s version of Hogarth’s Marriage à la Mode there is a dog in the first picture which the young girl whose betrothal is being negotiated rubs idly with her foot as she sits, head twisted, in a red chair. A cat snarls out at you, its ears flattened, in the final picture, where the bankrupted husband is supported in a pietà-like pose by his wife, who is sitting in the same red chair that she sat in as a girl in the first picture. There are not many simple readings here, and in that Rego is unlike Daumier and Hogarth, but like the Goya of the Caprichos. Even when they accompany specific texts, as many of the etchings and lithographs do, the result is a commentary on, rather than a pictorial realisation of Peter Pan, Mother Goose or Jane Eyre. The prints are not part of the exhibition but are illustrated in Paula Rego: The Complete Graphic Work.*

In Rego’s work collaboration has an unusually broad meaning, and includes printers and galleries (invitations to do work for specific exhibitions were the occasion of the wall paintings in the National Gallery restaurant), as well as living and dead writers. Her most important collaboration has been with models, and one model in particular, Lila Nuñez, who has appeared in – and, it seems, created characters for – many of the later pictures. These can seem like painted happenings, records of scenes acted out and of tableaux made in the studio. The same model takes many parts, the same props reappear. The most recent work in the Tate display is a triptych, The Pillowman. It grew from Martin McDonagh’s play about a writer of macabre tales who is being interrogated about the murders of children which seem to match murders in his stories. Rego’s mother and her granddaughter are given parts in the story of the pillowman – a black, stuffed monster who leads people to suicide. The seashore in one of the paintings is a memory of her Portuguese childhood. A photograph of Rego’s studio shows the props as well as the pictures.

The drawing in pictures like these ones (pastel makes them as much drawings as paintings) is good enough for its purpose – which is to say that it is very good indeed – but it is not engrossed in the pursuit of its own felicities. Rego has made drawing from life a tool which rises to the needs of stories. Because the models, the furniture, the clothes are all real, the images have something of the solid fleshliness that Courbet, say, achieved. This combination of the real and the imagined, of observed human presence and dramatic invention, is, so far as I know, unparalleled.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.