Robert Hughes has a great enthusiasm for Goya’s art, which he communicates in this biography, together with much useful information, forcefully expressed, about the rival factions at the Bourbon court, the Napoleonic invasion, the evolution of bull-fighting, what a maja was, what guerrillas were. This is mixed with some less useful observations – there were in those days priests who ‘groped boys’ and were ‘quite as bad’ as their modern counterparts – and some errors, as when Hughes claims that the curls of pubic hair in the Naked Maja are certainly the earliest in Western art. He concedes that little is known about Goya, yet takes us out shooting with him. Goya ‘liked the macho life . . . You didn’t need to be the duke of this or that to hit a partridge, or to blaspheme victoriously when a puff of dust flew from its ass and it came pinwheeling down, feathers awry, out of the hard hot blue air.’ The vivid image was perhaps suggested by the Caprichos etchings, in which falling winged creatures and even anal puffs feature, but it also removes Goya from the deferential and hierarchical society in which he lived.

Hughes follows most modern writers on Goya in rejecting the idea, so often found in the old literature, that his portrait of Carlos IV and his family (today in the Prado) was satirical, and he even proposes that the artist was, despite anticlerical tendencies, a true believer. All the same, like many who have written about Goya (notable examples are Francis Klingender in Goya in the Democratic Tradition and Fred Licht in Goya: The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art), Hughes argues that Goya is in some ways our contemporary; or that he was, at least, the first modern artist. Not unexpectedly, it is Goya as a painter of horror and atrocity who attracts most attention. Hughes contrasts the Meadow of San Isidro, painted in 1788 when the artist was 42, with the Pilgrimage of San Isidro, also in the Prado, of 1821-23. The former shows a pleasant picnicking scene while the latter, one of the very damaged murals removed from the artist’s house, depicts a ‘sluggish snake of thoroughly miserable-looking humanity crawling towards the viewer across an earth as barren as a slag heap’. It is of course the Pilgrimage which is taken as a philosophical statement: ‘Goya’s vision of humanity in the mass, in the raw, almost on the point of explosion.’ Hughes is impressed by the coarse violence of the handling as well as the subject matter, but if it were ever possible to reconstruct what these murals originally looked like we might be less inclined to think of Ensor, de Kooning and Bacon.

Early in his career Goya had been helped by Anton Raphael Mengs, the favourite painter of King Carlos III and the most admired artist in Europe, who was also an exceptionally eloquent and original writer on art (Hughes regards him as a ‘frigidly correct pedant’ and ‘one of the supreme bores of European civilisation’). Mengs’s greatest contribution to Goya’s success, however, was his decision to return to Italy in 1777, leaving no major portraitist in Spain to rival Goya. Paradoxically, Goya’s success in this genre owed something to his lack of thorough academic training, a shortcoming which makes Mengs’s support surprising. Goya’s vivid portraits, in complete contrast to those by Mengs, which skilfully graft the melting graces of Correggio onto court sitters, look as if they were painted with little premeditation. Hughes describes Goya as ‘one of the greatest draughtsmen in European history’, but this claim is made with reference to the sketches intended for or used in his prints. There are hardly any surviving drawings for his portraits, and many passages in them are, in the conventional sense, ill drawn.

Goya’s first success was as a painter of pastoral and modern comedy. His royal tapestry cartoons were large but were preceded by sketches (the Meadow of San Isidro is one) which collectors valued for their spontaneity and brio. Indeed, some knowledge of the oil sketch as a genre is essential if we are to appreciate Goya’s achievement as a painter. His teacher, Francisco Bayeu (who became his brother-in-law and protector), excelled in making such sketches in the style of Corrado Giaquinto, Mengs’s predecessor at the Spanish court. The popularity of the genre is evident: genuine preliminary studies were copied and ‘ricordi’ (which provided lively summaries of larger compositions) proliferated. By the last decade of the 18th century Goya had started to make independent cabinet pictures of the same size as his oil sketches and with some of the same freedom of execution; in the National Gallery, oil sketches by Giaquinto and Bayeu hang next to Goya’s oil sketch for a tapestry cartoon and his little cabinet picture of witches, and we can see that the latter, although a ‘finished’ picture, retains the qualities of the sketches. Transposing the vitality of the oil sketch into works of larger format was more difficult to achieve and it is hard to resist the idea that some full-length portraits of women and of children painted in the 1780s would look better if they were much smaller.

Goya first excelled with a pale palette. The Meadow of San Isidro is a perfect example: the chain of reclining figures in the foreground with its light blues and greys and dabs and dashes of creamy white, enlivened by touches of pink and vermilion, is rhymed with the pale buildings of the distant city, rather as the buff pink of the soil repeats the colour of the sky. In his great portraits of the 1790s Goya contrasts such delicate harmonies with a black background, making his sitters seem strangely spectral: as evanescent and vulnerable as moths flashlit against the night sky. The exquisite portrait in the National Gallery of Andres del Peral, painted, unusually, on wood in 1798, perfectly exemplifies this effect. It is reinforced by the slight hint of a flinch or wince, perhaps in this case the vestige of palsy, which several of his most sympathetic sitters exhibit.

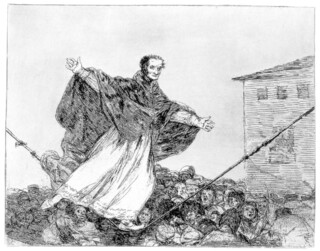

It was in the 1790s that Goya’s most original work was produced. And not only as a painter: Los Caprichos, his astonishing series of etchings with aquatint, were made in 1797 and 1798. (No doubt such work in black and white increased his fascination with the idea of using black in his paintings.) When he published these prints Goya claimed for the visual artist a moral purpose which had long been acknowledged in satirical poetry and comic drama. The depiction of marriage as a form of prostitution and the scenes of seduction and deceit may have originated in his indignation at contemporary social evils, although they look more like especially sardonic versions of stock comic episodes; but the scenes of witchcraft cannot be explained in these terms.

If Goya actually believed that women rode broomsticks, he was at one with the most reactionary elements in the Catholic Church, forces he appears to have detested. Hughes wonders whether these witchcraft prints were a disguised attack on the Church, and notes the parallel between the rites of the witches and those of the priesthood. What is certainly true is that placing scenes of grotesque deceit, erotic initiation and ritual cruelty on the part of witches next to analogous practices sanctioned or indulged by respectable society helps to point up the irrational basis of the latter. Altogether the most remarkable quality of Los Caprichos is the way a cynical, demotic commentary accompanies an ostensibly Enlightenment project – the exploration of cruel social conventions and popular superstition – making it hard to reconcile with the optimistic agenda of reforming intellectuals such as Gaspar de Jovellanos, although Goya may have felt close to him, and painted him with evident sympathy.

Hughes simply asserts that the Caprichos were ‘meant to be popular art’, and notes that Goya ‘wasn’t "above” the pleasures of a hot tabloid news story’. But the uneducated mass of the people did not buy etchings, and the little paintings of rape, murder, violent robbery, incarcerated maniacs and animals being tortured that Goya made around 1800 were commissioned or acquired by noble collectors. ‘What may have seemed vulgar’ to connoisseurs ‘now looks prophetic’, Hughes tells us. But he then admits there is no evidence that Goya was considered vulgar. What is most ‘prophetic’ for Hughes about Goya seems to be the way that his second great series of prints, the Desastres de la Guerra, executed in the second decade of the century but not published until 1863, prefigures the great wars of the 20th century as well as illustrating the consequences of Napoleon’s invasion of Spain.

Hughes is not unusual in regarding these prints as a passionate humanitarian protest, as an assertion that ‘torture, rape, despoliation and massacres’ were ‘intolerable’. Certainly Goya’s imagination was ignited by atrocity. How much this had to do with moral outrage is difficult to determine. Some vestige of morbid fascination seems to me to mingle with the disgust and it is easier to accept that he was haunted by these horrors than to suppose that they were composed as an ‘anti-war manifesto’. For Hughes the image of the man with outspread arms shot by a firing squad in Goya’s Third of May is equivalent to the ‘few photo images that leaked out of Vietnam’. This painting, together with its companion picture, The Second of May, was intended by Goya to demonstrate his patriotic credentials to the restored Bourbon monarchy by commemorating the insurrection against the occupying French and the cruel reprisal of the following day.

Nothing in Hughes’s book is more peculiar than his indignation over the fact that these two paintings were not ‘installed with pomp and honour on some suitable public wall, where the pueblo who were the collective hero of Goya’s commemoration could see and reflect on them’. The paintings are not recorded for certain until twenty years after they were completed and were then ‘not even on display’. Indeed, the paintings are not known to have been on public view before 1872. ‘One wonders why, since Goya could hardly have placed himself more fully or passionately on the side of the Spanish people.’ One of the two chief representatives of the people in the Second of May is hacking in frenzy at an officer who is already dead and the other is stabbing a handsome white stallion. It would have been very easy to represent them more heroically. I think it most unlikely that the pueblo would have much cared for these paintings. And how is this supposed enthusiasm for the masses to be squared with Goya’s own image of the crowd? Are we to imagine that ‘snake’ of religious fanatics in the Pilgrimage arriving in the Prado, to be improved and gratified by Goya’s patriotic canvases? A popular audience in Spain would have been conditioned by Catholic devotional art to expect to see the face of a martyr transfigured, and not displaying the strange, demented, animal stare which the victim with outstretched arms shares with the frenzied stabbing assassin in the pendant picture.

The atrocity picture has a long history. Those which were made at the time of the Wars of Religion and of the imperialist ventures in the early 17th century had official sponsors. William Sanderson in his Graphice of 1658 notes how such imagery can ‘insinuate into our most inward affections’ and, as an example of this, cites the effectiveness of the decision ‘to enforce a more horrid reception of the Dutch cruelty upon our English at Amboyna in the East Indies’ by having it

described . . . into a picture [that is, a plate] to incense the Passions, by sight thereof; which truly (I remember well) appeared to me so monstrous, as I then wished it to be burnt. And so belike it seemed prudentiall to those in power, who soon defac’d it; lest, had it come forth in common [that is, been published], might have incited us then, to a nationall quarrel and revenge.

In the case of Fernando VII and his advisers, it is easy to understand why they would have considered it ‘prudentiall’ to suppress – or at least fail to exhibit – a picture of a popular uprising against mounted soldiers.

John Ruskin burned an album of Los Caprichos. Hughes observes that, ‘if nothing else could make you sense that Ruskin was cuckoo’, this ‘peculiar deed’ would. But it is easy to understand the horrified response of someone with profoundly humanitarian feelings who was also mentally unbalanced. It is unlikely, too, that Ruskin would have seen the Disasters of War and the bullfighting etchings as belonging to entirely different categories, as Hughes seems to. Hughes has no aversion to the torture and massacre of animals, as is obvious from the relish with which he (and Goya) blast partridges out of the sky. He enjoys torturing the wimps among his readers by pointing out the dangling intestines and the blood pouring from the anus of the gored horse which confronts the ‘superbly profiled’ bull in the painting the Getty Museum bought at Sotheby’s a decade ago. But is the profile superb? The intervals are less eloquent, the encounter far less dramatic than we would expect from Goya’s etchings of this subject, and the composition is weaker than in the earlier works from which it is derived. The handling is rich and thick but turgid, and unlike any painting known for certain to be by Goya. We really should be told that the authenticity of this painting has been disputed.

Hughes mentions that curators at the Prado have expressed doubts in private about some of the ‘Goyas’ there, but he seems to be unaware that Goya had many imitators in the 19th century, and even supposes that the artist’s son, Xavier, was not active as a painter. He does not mention the debate which has led to a question-mark being placed over both the most famous painting by Goya in London (the portrait of Doña Isabel de Porcel in the National Gallery) and the most famous one in New York (the Majas on a Balcony in the Metropolitan Museum).

Doña Isabel was acquired for the National Gallery in 1896. Goya’s popularity in the 1890s can be seen from the tableaux enacted by New York’s leading society beauties in Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth (published in 1905, but set about a decade earlier), in which Carry Fisher, ‘with her short dark-skinned face, the exaggerated glow of her eyes, the provocation of her frankly painted smile’, presumably assisted by a good deal of black lace, impersonates a Goya which must have been as recognisable to her public as the pictures by Titian, Van Dyck, Veronese, Watteau and Reynolds that her rivals mimicked. It may have been the London picture that Wharton had in mind. In any case, it now seems likely that this picture was, like Carry Fisher’s performance, a brilliant imitation. It is too frankly ingratiating, the glow of the eyes is too exaggerated, the face rather too precisely drawn and smooth, despite the dashing impasto of the clothes.

In his excellent survey of Goya’s reputation (Goya and His Critics, published in 1977) Nigel Glendinning reproduces a photograph of a tableau performed in Madrid in 1900 in which two society beauties, a German and an American, escorted by two Spanish noblemen, re-created the Majas on a Balcony, a painting which Berthe Morisot persuaded Mrs Havemeyer to buy four years later. Mrs Havemeyer later left the painting to the Metropolitan Museum, where visitors will now find this foundation stone of modern art labelled as ‘attributed to Goya’. This formula, beloved of curators, perplexes most members of the public but if they read on, they will discover that it is ‘perhaps’ a pastiche by Goya’s son. The label concludes that it ‘remains possible’ that the painting is a ‘damaged original’. In 1995 the Met had the courage to exhibit the superior and indisputably autograph version of this composition in a private collection side by side with their painting. A superb analysis of the difference between the two by Juliet Wilson-Bareau was published in the Burlington Magazine for February 1996; she was also the first scholar to cast doubt on the London portrait.

These attributional problems are not marginal: it is now clear that Goya was widely imitated, even before he became highly influential, and also that when he did become influential the false pictures were especially so. In them the handling tends to be exaggerated, often with a thick impasto slashed and smeared with a palette knife. Indeed, they look especially modern. In assessing Goya’s originality we need to exclude these works. More generally, it would be helpful to concentrate on his own period rather than on what seems prophetic of today or yesterday. At the same time we should reflect on the fact that Goya was most exciting for adventurous collectors like Havemeyer and for artists such as George Bellows around 1900, when there was very much more confusion as to what was really by him. Exactly the same was true of Velásquez half a century before. Scholarship seals the doors through which the great artists of the past rushed – or seemed to rush – eagerly addressing us in our own language.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.