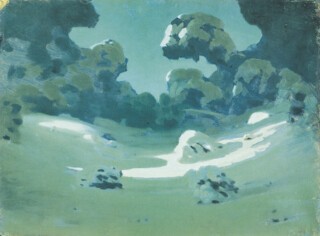

In the early days of colour television you could buy a device which, it was said, would convert your black and white set. It consisted of a transparent plastic sheet, half blue and half green. You stuck it over the screen, in the hope that once in a while the sky and the prairie would divide the picture in the right proportions. Arkhip Kuindzhi’s Landscape: The Steppe of 1890 is the only painting I know which would allow that simple scam to work perfectly. It shows featureless grey sky above almost featureless green steppe, which stretches right out to a distant, dead level horizon. ‘Look,’ it seems to say, ‘this is all we have – an endless plain and high grey skies.’

Painters of flat land, denied rocks, hills, torrents and mountains, turn to trees (in groves, avenues and forests); to the sky and clouds; and to light as it changes from sunrise, to high noon, to sunset, and to moonlight. With these they are able to dramatise plains, prairies, steppes and meadows. In the 17th century the Dutch did it. The 19th-century Russian painters whose work is now being shown at the National Gallery did it too (Russian Landscapes in the Age of Tolstoy is on until 12 September). It is not that other landscape traditions made no use of the brightening and fading of the light, but they had less reason to explore it. Canaletto’s Venice is always seen in clear sunlight, Claude’s castles and coves are always bathed in the same crepuscular glow. Their pictures are staffed with little figures. Palaces border canals or rise on promontories. There is always something new to look at. The endless steppe is, well, endless; it needs to be lit.

So the titles of the Russian pictures tell you to think of time, weather and season rather than location: Morning on the Dniepr, Morning in the Country, The Rooks Have Returned, After the Rain, A Ploughed Field at Evening, Late Autumn, Forest View at Noon. In their time these pictures were radical, as pure landscape was in any country with an established academy which supported the hierarchical pretensions of history painting. Moreover, unpeopled landscape was as difficult for an audience newly exposed to it as abstraction would be later.

When you abandon stories you may still have a message. The aspects of nature that dwarf us can suggest other powers beyond our grasp. In Russia, pictures of plains and forests, snow, sun and thaw, were evocations of the motherland. The emotions they played on were consonant, at least implicitly, with ideas of spirituality and constancy, of emptiness and isolation. The considerable physical size of some pictures is just one way the scale of the Russian landscape is acknowledged. The eye is sometimes carried to the point where the plain drops below the distant horizon. In some cases the viewer becomes like the figure that stands dwarfed in the foreground of Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea, which is reproduced in the catalogue alongside Kleist’s reaction to it: ‘It was like someone having their eyelids cut off.’ Even landscape can be painfully revealing. The German connection is important, but if one lists influences one must also include the French (Théodore Rousseau, Monet even) and the English (Constable).

Literature is more helpful, when you try to understand what these pictures meant to the people who made them and those who first saw them. Turgenev looked after Russian artists. One of them, Vasili Polenov, said many of his themes came directly from Turgenev’s fiction. Chekhov didn’t like it when his friend the painter Isaak Levitan, who had a freer manner, made fun of realism, but Sjeng Scheijen, in a chapter in the catalogue,* suggests that Chekhov was the first writer ‘whose way of looking at the Russian countryside was inspired by landscape paintings’, and quotes a passage from ‘The Steppe’ to illustrate the point: ‘The hills had vanished and wherever you looked a brown, cheerless plain stretched away endlessly . . . Between the cottages and beyond the church a blue river was visible and beyond it the hazy distance . . . The sheer scale of it bewildered Yegorushka and conjured up thoughts of the world of legend . . . Who needed all that space?’ Although the responses and aims of painters and writers were analogous, literature was culturally dominant, as the title of this exhibition indicates. To say that Turgenev and Chekhov’s Russia is more interesting than Shishkin’s or Levitan’s is to acknowledge something the painters’ contemporaries would also have admitted.

In this show, solid versions of pedestrian subjects (skies, fields, rivers, trees, lakes) can be pleasingly provincial. Some are provincial in the negative sense, such as Nesterov’s excursions into myth (Dual Harmony – a couple by a swan lake) and religion (St Sergius of Radonezh). These are boring because they are too far from the spirit of what they try to evoke.

The easiest pictures to enjoy are examples of fresh, direct observation, works which if not actually painted in the open air must draw on studies made from life. (When he was a student, Ilya Repin – whose Barge-haulers on the Volga and Religious Procession in the Province of Kursk are among the small number of Russian 19th-century paintings well known in the West – was told to expunge bits of direct observation and copy something from a Poussin in the Hermitage.) There are show-stoppers, of which the most vulgarly eye-grabbing is Kuindzhi’s Moonlit Night on the Dniepr, which made a great sensation when it was first shown in 1880, hung against a black curtain in artificial light; people were convinced the bright path of the moon on the water was somehow lit from behind. It shows great technical ingenuity. Some of the glistening brilliance of the moonlight seems to derive from the way light is reflected from paint scored with fine parallel lines – as though run over with a stiff, dry brush. Shishkin’s eight-foot wide Mast-Tree Grove would serve very well as one of the panoramic backgrounds natural history museums used to run behind tableaux of stuffed animals, but it is hard to deny its effect. Popov’s Morning in the Countryside, which shows a woman leaning on a bridge, seen from low down, has some of the modest, precise brightness that you find in smaller Danish pictures.

These Russian painters were discovering and rediscovering the look of their country. It isn’t surprising that their work brings to mind that of contemporary American painters who were also finding ways of painting woods and prairies. There are no masterpieces here, but the echo of high aspirations, the demonstration that some of the imagery of art and literature was shared, enlarges your view of the culture to which both contributed.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.