Vuillard’s early work figures in standard histories of modern painting. What he did between the wars is largely ignored – people felt it was kinder to forget about it. It would be nice to say that the exhibition at the Royal Academy until 18 April confutes received wisdom. It doesn’t. All you can say is that the early rooms offer pleasures which the late ones cannot expunge. The challenge the curators of the exhibition offer to this judgment is bold and unconvincing.

In 1888 Paul Sérusier brought back to Paris a landscape he had done in Brittany under the guidance of Paul Gauguin. A painter, Gauguin had told him, should translate what he saw into unmixed colours: if a tree looks green, make it the strongest green you have, if a shadow is a bit blue, make it truly, deeply blue. ‘Thus,’ Maurice Denis wrote, ‘for the first time . . . was presented the rich concept of the flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order. And so we realised that every work of art was a transposition, a caricature, the impassioned equivalent of a sensation experienced.’ Sérusier’s Talisman was the seed from which much of what was new and remarkable in the painting of the Nabis (nabi = ‘prophet’ in Hebrew and Arabic) arose. Not everything, for the work of the group was varied in size and subject-matter: from fans and book illustrations to stage scenery and wall decorations, from mythology to nursemaids in the park. And there are other relationships to point to – the graphic inventions of Lautrec’s and Degas’s prints; the patterned surfaces and flattened space of Japanese woodcuts.

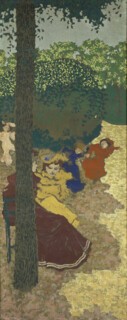

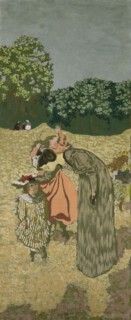

But it was the new way of handling colour which made it possible for some of the Nabis – most tenaciously Bonnard, but at first Vuillard and others as well – to take painting as a record of how things look beyond Impressionism. The Impressionists had already made the surface of the picture something to be conscious of, rather than something to look through. They heightened colour and moved the normal tonal range up an octave or so. But they still stuck quite closely to observed fact. They did not seek Denis’s ‘impassioned equivalent’. The pictures in the Vuillard exhibition which get closest to that goal are the little ones, mainly interiors, single figures or pairs of figures, painted between 1890 and 1900. Women wearing and handling patterned fabrics – his mother, with whom he lived until the end of her life, was a dressmaker – fade into patterned wallpaper, as hard to spot as leopards in dappled shade. The colour is ravishing, the claustrophobic rooms bring to mind childhood visits to grandparents’ houses in which things are dim and crowded, and smell strange. There is enough of the realist/Impressionist impulse left to make light – in particular lamplight and light from windows against which figures are silhouetted – part of the subject-matter. To get a sense from Japanese prints of what it would be like to be in a 19th-century Japanese room requires imaginative steps which Vuillard takes for you in his Paris interiors. His figures – the dressmakers, the children in the park in the big decorative panels he painted for Alexandre Natanson in 1894 – have, like Bonnard’s black-smocked infants on the way to school, a Japanese accuracy and economy: so few marks, so true about gestures, movements and clothes.

In most of these early pictures people go about their business – few of them face you. This is at the root of another satisfaction the pictures give: you are not being challenged, it is not just that no eye commands you from the canvas, no eye commands anyone within the picture either. You are watching life going on.

Then, between the wars, a change took place: he began to make his living by recording grander interiors and richer people – most lived on the border where fashion and money meet art. The difference between Countess Marie-Blanche de Polignac (the daughter of Jeanne Lanvin, the dress designer) in her bedroom, say, or the motor manufacturer Lucien Rosengart in his office, and the domestic interiors of the 1890s, in which figure and ground make equal claims, is of kind, not degree. Vuillard said he was not a portrait painter but a painter of people in their rooms. In a portrait the face is the subject: the countess’s morning-glory chintz, even the sofa which dominates one of the portraits of Yvonne Printemps, do not distract you for long. When you want to show both an individual face and the space the figure inhabits, the angle of view widens and the perspective steepens. Shallow space – the frieze with figures of the earlier pictures – gives way to spaces in which figures can be separated from their surroundings. What seem to be small rooms – a dining-room, Vuillard’s mother’s workshop – are replaced by the countess’s big bedroom and fashionable drawing-rooms. When he paints his mother again, making her part of the décor – crouched down lighting the stove in one corner of the picture – the buff, paperless walls, the ascendancy of appearance over imagination bring to mind early 19th-century oil sketches rather than 20th-century discoveries and adventures. In the process the pictures become conventional; many are unpleasant to look at.

One way to explain and excuse this is to say that they are meant to be satirical. The catalogue note on the early (1914) portrait of Marcelle Aron suggests that ‘the painter’s ironic lucidity manages to push the harmonic restraint of Ingres’s Madame de Senonnes into total and gaudy disarray’ – as if ‘gaudy disarray’ was in itself desirable.* ‘This version,’ the catalogue goes on, ‘has all the marks of a game of displacement based clearly on an appreciation of kitsch. It may well be that the work, more than simply a portrait, is actually a brilliant inquiry into taste.’ Looking at the picture doesn’t make this more convincing and, as far as I can make out, Vuillard’s journal entries do nothing to bear it out. The entries cited in the catalogue deal with problems and irritations common to all portrait painters. Yet Guy Cogeval’s catalogue introduction gives readings of many of the late portraits which go beyond even the notion that he was an amused critic. Vuillard, he says, was ‘indulging in a cruel puppet show’. Elvire Popesco, the actress, has the ‘sullen pose of a brothel madam’; Misia Sert with her niece is ‘one of the most ferocious examples of Vuillard settling accounts with the past. The sphinx who had tormented the shy, lovesick painter in his youth sits enthroned in a flashy drawing-room, a self-satisfied, puffy-looking old trout, holding her horrid little dog in her arms.’ This sort of picture, he writes, is ‘“bad painting” before its time’. But the bad paintings are not bad enough for that. There is no sign that Vuillard’s tongue is in his cheek. What Cogeval says about the sitters can, with a few twists, be said about the paintings.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.