The Second World War paraphernalia in the Imperial War Museum is not just tanks, guns and half-tracks. There is a sailing dinghy – one of the boats which evacuated soldiers from the Dunkirk beaches – as well as posters about careless talk costing lives and, high above you, propeller-driven aeroplanes, as archaic now as tournament armour, their fuselages and wings not quite smooth, as though an apprentice panel-beater had been at work. The effect is less bellicose than melancholy. Eric Ravilious’s work as a war artist has the same quality.

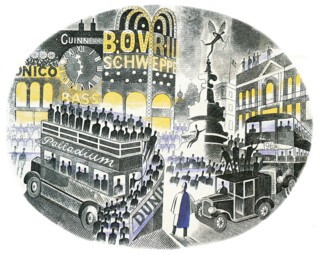

The exhibition of his work at the Museum until 25 January includes Wedgwood mugs, plates and bowls, furniture, a pocket handkerchief, printed ephemera for famous shops, book illustrations and poster designs. These bits and pieces, decorated with scenes and figures which owe their formal qualities to the last twitch of Art Deco and to a combination of 19th-century popular art and 17th-century engravings and tapestry designs, are a proper complement to the watercolours.

When he was sent to war Ravilious turned his attention from empty rooms, small-town streets, ships, old machinery and the Downs to coastal defences, aeroplanes, more ships, a control room, a sick bay and the insides of a submarine. But there is no sense in his pictures that England, or even his subject matter, has changed profoundly. The linoleum will still be cold to the feet; the curves of ancient hills with pictures of horses and men cut into the chalk are not very different from the curves of coastal defences topped by gun emplacements. In all the pictures, the elimination of human beings – or their relegation to the middle or far distance – stresses the isolation of the implied observer.

The paintings in the exhibition are of real places. Ravilious was a poet of the real and the frugal – and ‘frugal’ not just in the kinds of bare room and bare landscape he favoured as subjects. There is also frugality of means: all the pictures are more or less to the same size; the underlying pencil drawing is neat, almost parsimonious. It often looks as though a ruler was used, so delicate and accurate are the straight lines. There is no sloshing about: the paint is applied with a lightly loaded brush and the surfaces, of the sea, of hills and machinery, are described in broken washes and fine hatched lines and rows of dots which leave the texture of the white paper showing through. The lines describing curves are precise – each the result of a whole-arm movement, not a finger-driven squiggle. The width of the lines varies as pressure on the brush increases and decreases. Ravilious was an engraver; it is no wonder his brush takes on the character of a burin, or that he describes volumes with rows of parallel lines as engravers do. The shapes and textures in his pictures represent real things, but they also have an abstract graphic life of their own.

Ravilious is not difficult to place technically and culturally. He admired watercolourists like Francis Towne (there are a couple of his pictures in the exhibition, so you can make comparisons) and John Sell Cotman. He took from them – or so one guesses – ideas about the relation of watercolour wash to the drawn structure underneath, and a way of simplifying landscape into a pattern. In his work for Wedgwood and in his illustrations he offered a refined, ironic commentary on 19th-century popular art; his wood-engraving of top-hatted cricketers was used on the cover of Wisden until a very few years ago. The coolness of his work makes it unsurprising that he made no attempt to use art to engage with politics in the 1930s, or the more brutal facts of war in the 1940s. This was not a sign of ignorance or indifference (although Edward Bawden did make digs about the commission for Coronation mugs) – the biographical parts of Alan Powers’s catalogue essay make that clear.* It was not just that a style developed in the service of Fortnum and Mason wouldn’t work as agitprop. The disengagement which characterised the style Ravilious had developed was both personal and part of the strand in English interwar culture that was wary of rhetoric but had a sentimental attachment to the fairly recent past. Wax flowers under glass domes, rummers, Windsor chairs, country cottages – fabrics rather faded, machinery a bit rusty, the surrounding countryside marked by ancient earthworks as well as agriculture. When the war came, Ravilious, who took pleasure in painting such things, found that the treatment which worked for them worked equally well for military equipment. It could look like a retreat from the reality of war – Ravilious was more than once accused of self-indulgence. A refusal to be shaken out of a degree of disengagement was far from unique; it can be found, for example, in Jocelyn Brooke’s fictional/autobiographical trilogy, for which Ravilious’s watercolours would be appropriate decorations.

What is difficult to track down is the source of the feeling many of the pictures give that these are dream landscapes, places you know to be real, but where you feel something has happened, or will happen, which lies outside ordinary experience. Some of these intuitions can be explained iconographically: the absence of people, emphasised by the wide angle of the views; the cool quality of the light reflected from the wrinkled surface of the sea or falling evenly with soft shadows into rooms in paintings which (unless the sun is actually shown going down) say very little about the time of day.

Beyond that one is left to speculate. Powers sifts psychological and historical evidence in a suggestive but inconclusive search for convincing connections. He can point to a rejected religious upbringing as one reason for Ravilious’s detachment (his father, an antique dealer, spent time in pursuit of meanings in the Old Testament), and more generally to the feeling current in the 1930s that the future of English art lay in an appreciation of the connection between landscape, people and history. Beyond that, the pictures are as deep as you want to make them. Ravilious himself never tipped his hand. When he went missing on a search and rescue mission from Iceland in 1942 he was not yet 40. A talent, peculiarly well-suited to a version of England and English life in which wit and mocking self-depreciation both had a part, was lost a few years before that way of projecting the national character reached its apotheosis in the Festival of Britain. Had he lived he would surely have done things for it; in the years that followed he would have been marginalised. The show gives immense pleasure. The flavour of the pictures, like the brushmarks themselves, is dry enough to combat the sweetness lurking in the view of England they embody.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.