There is armour, an insect-like carapace; and there is drapery, a second, looser skin. Any garment can be placed somewhere along the gradient between the two. The carapace is stiff; it may have curves, but they will not be caused by the fabric’s resting passively on the body’s surface. A modern leader-of-the-nation’s lounge suit, Queen Elizabeth I’s pearl-embroidered dresses, the padded jackets and breeches of her courtiers – all these have more carapace-like, shape-imposing qualities than shape-taking ones. At the other extreme are flowing, liquid garments. Think of Nike adjusting her sandal or the Victory of Samothrace, of shifts and nightgowns, of bits of back, breast or shoulder seen through transparent fabrics which follow the body as it moves.

Body-accepting clothes are no easier to make than body-denying ones. The highest skills of the pattern-cutter and dressmaker are required, one is told, to make flowing garments secure and decent and to discipline what may look like careless folds into flattering rhythms. Ossie Clark was very good indeed at the physical business of dressmaking. What must have been a fine native talent was refined at the Royal College of Art when that institution was at its height as a forcing-ground for young designers. Many (although by no means all) of the garments he made, often in fabrics designed by his wife, Celia Birtwell, were of the flowing kind. He is honoured until next May by a special display in the costume court at the V&A in which the body-friendliness which so delighted his glamorous clients is still engrossing and delectable.

The book, Ossie Clark 1965-74 by Judith Watt,* and the display cover less than a decade: the short period during which the clothes Clark designed made him as well known as the rock stars whose wives were among his most loyal clients. In Watt’s book, Clark’s financial failure and physical and moral decline are addressed mainly in terms of questions about the organisation of the French and English fashion industries and his inability to find the support he needed – or to make good use of the support he got. She suggests that he needs to be rescued from the view he gave of himself in his diaries. From what Jenny Diski wrote about them in these pages† it seems clear that if the frocks are to justify the life they had better be good.

The carapace/shift balance in English fashion tipped at the beginning of his glory years. The time for dresses with very short skirts, straight seams and geometric patterns (one dress at least borrowed literally from Mondrian) was coming to an end. In these clothes rectilinear shapes were imposed on the body; they had no more flow than the tabards of the playing-card courtiers in Tenniel’s Alice illustrations. When I look back on the miniskirt years, during which I was a careless, ill-informed observer, always more interested in the person than the frock, I find it difficult to recall just how many women showed their thighs and shopped in the King’s Road. Enough certainly to make the curved and plump feel they were not well served. Clark was after something very different: clothes long enough to flow; clothes which when they were fitted close were tight in a way which acknowledged the shape of a woman’s body.

He wasn’t the fat lady’s friend either. Jenny Dearden, who worked in Quorum, Ossie Clark’s shop in the King’s Road, says of the charmed circle of people who came and went: ‘You had to look right. You had to be skinny and you had to be pretty. A lot of people there weren’t fantastic-looking, but if they dressed in the right way . . .’ And you couldn’t dress right, even in diaphanous prints, if you made the thing look like a tent. But if they were right for you, Clark’s clothes made women feel great. This was how you wanted to look, how you wanted your body presented.

Women are less limited than men by the shape nature has given them. Men can be padded and corsetted to a degree, but the soft flesh of women’s breasts and a thicker layer of subcutaneous fat encourage a greater degree of sculpting. When a new silhouette becomes desirable more women are able to display it than an analysis of the spread of body types would suggest possible. Pictures of Adam, generation by generation, show, roughly speaking, the kind of well-muscled male body you will find in any gang of scaffolders. This is the norm whatever the style. Eve, on the other hand, may have a Cranach-like pear shape or Rubens curves. Tintoretto gives his female nudes a solid sleekness, more muscular than current taste allows, while Tiepolo’s would fit Clark’s clothes very well.

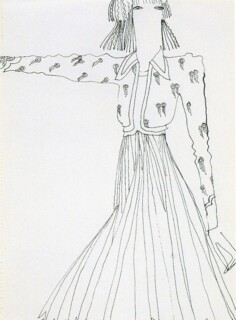

As a boy Clark buried himself in copies of Vogue from the 1930s and 1940s. In them there were fashion illustrations which made it easier than photographs do to see what clothes might look like in the real world. They showed women wearing them on trains, on boats, in drawing-rooms. Photographers and models, having to give glamour to lens-rendered reality, need more extreme poses and more striking contrasts to bring home a point. While illustrators made garments look good by explaining the meaning of a seam, the swing of a skirt or the drop of a hat brim with a line which had something of the individuality of handwriting about it, photographers have to make the point by doing something balletic with the body. Fashion drawing is different from fashion illustration of that classic kind. When Clark and Birtwell drew and drew, filling sketchbooks and developing ideas, they were not making fashion illustrations: they were playing with ideas for making clothes in the way architects play with ideas for plans and elevations. Fashion illustrations are to fashion drawings what architects’ sketches are to presentation drawings of buildings in perspective.

Fashion drawing has its own very odd conventions. For example, figures are drawn with exaggeratedly long legs, narrow waists and small heads – which perhaps explains the grotesque proportions of the Barbie doll. When I visited the exhibition at the V&A there was a class of fashion students making drawings, as Clark did in his Royal College years. Looking over shoulders I saw many Barbie silhouettes. Even girls who are not trying for fashion as a career, but don’t care much for drawing anything else, will cover pages with pictures of girls – themselves – dressed in imagined finery. Birtwell was one of these, and from childhood drew the same figure: a stylised face rather like her own and, below it, garments in bright floral or geometric designs – pretty, gaudy and light-hearted. More Claris Cliffe than Dufy, but sharing with Dufy a sense of pattern and of what happens to pattern when it is applied to a surface which folds and drapes. Clark’s drawings make clear in a few lines how a garment was to work: how the short jacket was to flare over the hips, how Mick Jagger’s white jumpsuit was to gape sexily, how the seams and buttons on the front of a jacket would articulate the surface. Accounts of his way of working – Birtwell’s, for example – suggest why the clothes were so desirable and so good to wear: ‘He’d get the toile, draw what he wanted from the mannequin, lay it flat and cut it. I don’t think anyone knows how to do that any more, and that’s what made them fit the body and made you feel nice because it was built round a 3-D form.’ The vivacity of Birtwell’s prints, as much as the suavity of Clark’s cut, prevents the dust which dulls yesterday’s fashions from settling here.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.