The leopard, the giraffe and the macaw follow no fashion – they are born elegant and appropriately insulated. They cannot, season by season, startle with new patterns of fur or feathers. People can.

We may, snake-like, shed worn-out clothes; we may become bored, disgusted or embarrassed by the way we look. Or, better, we may decide to be inventive, emulative and playful. But whether new clothes are a response to frayed cloth or booty from a shopping spree, once they are on your back they are not neutral decoration any more than the spots on a pelt which mimic dappled shade are neutral, or the bright, incommoding tails evolved by birds to attract mates. They signal moods, intentions and desires; they identify and camouflage. Fading into the crowd or standing out from it, saying ‘this is who I am,’ ‘come on’ or ‘back off’: these things are managed or implied by fashion choices. Not to choose and not to care is to conform by default – which is the most insidious choice of all, and self-defeating.

The look of a giraffe or macaw is evidence of breeding success in the generations of ancestors through which the species wandered to achieve drabness or splendour. Although our fashions evolve year by year, rather than over millennia – and are an aspect of social, not physical change – their effect, too, depends, very often, on basic appetites. We can advertise differences by modulating the way those appetites are addressed. ‘Good taste’ is the most divisive, or at least most curious, modulation of all. Almost by definition, it is invisible to (or beyond the means of) those who have not got it. What animal skin is designed to have a meaning for only a few members of the species?

‘She’s certainly very simply got up,’ Proust’s Albertine says of Madame Elstir, ‘but she dresses ravishingly, and to arrive at what you find simple she spends like no one’s business.’ High fashion was, and is, also a high craft, exorbitant in its use of labour. At the beginning of the 20th century, it was supported by women who wore expensive clothes, but at the beginning of the 21st the clothes are loss-leaders: they publicise the off-the-peg lines, accessories and scent, which balance the books of the fashion houses. So while the exclusive price tag of high fashion is no problem if it is to function as an advertisement – a Formula One Ferrari can still be used to boost anything from a little Fiat to motor oil – aesthetic exclusivity is a problem. Good taste, of Madame Elstir’s kind, is at a disadvantage when what is required of a frock are magazine pages and television news clips in which the origin of a garment is beyond doubt. Versace is not the only fashion house to come out with collections headed by outfits that look as though they were intended for a fancy dress ball.

At the Barbican there are currently two exhibitions about fashion and its presentation. Rapture: Art’s Seduction by Fashion since 1970 and David LaChapelle’s photographs both run until 23 December. An exhibition at the V&A of Gianni Versace’s clothes runs until 12 January.* All three tangle with the paradoxes of taste and exclusivity. LaChapelle embraces Truman Capote’s ‘Good taste is the death of art.’ In his engaging introduction to the catalogue he explains that his work is just a continuation of what his mother used to do – dress the family up, make sets and take snaps. His strongest complaints are reserved for the publicists who stand between the celebrities he photographs and the antics he would like them to get up to. Not that he does badly in getting them to strip down or paint up in wild, pornographic, strange or silly ways. The colour range in his photographs runs from boiled-sweet pinks and reds to plastic-duck yellow and swimming-pool blue. A video shows him with a camera on which is mounted the kind of ring-flash medical illustrators use. The results are bright and shadow-free. His pictures appear in style and fashion magazines, but in Playboy and advertising too – the show is sponsored by Lavazza, the coffee company he has shot ads for.

The strongest signals clothes can give are sexual. If, as seems to be the case, there are cycles of visual permissiveness – measured crudely by the likelihood of a woman’s dress allowing a naked breast and nipple to appear – we are now creeping back towards what was allowed in Restoration portraiture. LaChapelle’s shot of the actress Drew Barrymore in a pink and white waitress’s uniform and carefully laddered stockings, surrounded by half grapefruits, each with a cherry on top, echoing the nipple of her exposed breast, is iconographically not too far from some of Lely’s portraits.

Versace does not go quite so far and suggests more than he shows. That black dress Elizabeth Hurley wore to a film premiere – slit and safety-pinned up the side and open almost to the waist in front – has its place in a history which includes the dress with its black calyx-like bodice out of which white shoulders flower in John Singer Sargent’s portrait Madame X: a dress as famous as the Versace, and more scandalous. The anxiety/hope that a woman may fall out of her frock goes back further still. In Aurora Leigh, ‘that bilious Grimwald’ (a critic) observes the villainous Lady Waldemar:

Those alabaster shoulders and bare breasts,

On which the pearls drowned out of sight in milk

Were lost excepting for the ruby clasp!

They split the amaranth velvet-bodice down

To the waist or nearly.

Grimwald gives a ‘a low carnivorous laugh’, and says:

A flower, of course!

She neither sews nor spins, – and takes no thought

Of her garments . . . falling off.

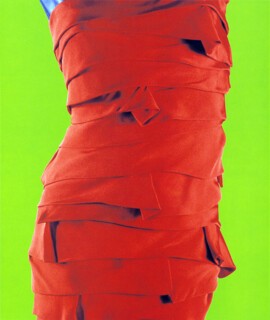

Such sexual teasing, which guarantees a feeding frenzy among Oscar-night photographers, may seem crude; by itself, though, a tease is not nearly enough – the Versace show is worth a visit to see from close-to how these clothes combine taste-free inventiveness with an appetite for craft and for wilful oddities of cut and construction (these technical skills are demonstrated in the dress shown above). Many of them would look as odd on the street as a girl waggling ahead of you with a catwalk strut, but set them on the right stage – at those events, like film premieres, which are part party, part masque, part advertising campaign, the modern equivalent of the ballets where royals played the gods – and their extravagance becomes merely (and appropriately) theatrical.

Rapture, in so far as it follows the subtitle of the exhibition, shows art not just seduced, but left destitute, by fashion. Chris Townsend’s catalogue introduction begins by describing the way clothes shops have driven artists and their galleries out of the SoHo lofts and streets where the School of New York once flourished. The exhibits include some very pretty asides on clothes: Maureen Connor’s 1981 Birth of the Bustle, for example, in woven reed and organdy is as beautifully made and as pretty as anything in Versace. But most of the other attempts to outflank fashion end up as commentaries which have much less power than the commercially honed objects from which they attempt to distance themselves.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.