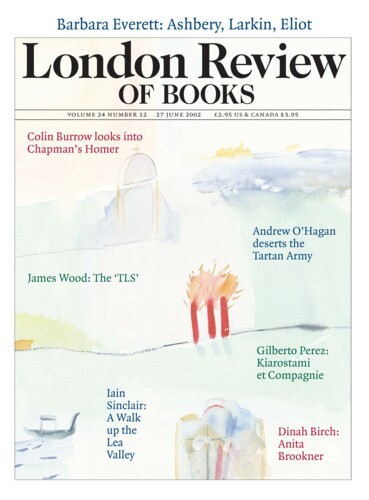

‘Best Value’. Somebody somewhere, well away from the action, decided that this banal phrase, implying its opposite, was sexy. Best Value, with the smack of Councillor Roberts’s corner-shop in Grantham, the abiding myth of Thatcherism, has been dusted down and used in every PR puff of the New Labour era. Best Value. Best buy. Making the best of it. Look on the bright side. Spin doctors, post-literate and self-deceiving, had no use for subtlety. Best Value. They hammered the tag into their inelegant, over-designed freebies. These glossy publications, political correctness in all its strident banality, existed to sell the lie. Best Value.

Government-sponsored brochures are got up to look like supermarket giveaways. Strap headlines in green. Articles flagged in blue. Colour photos. Designed not composed. That’s how the planners (the strategists, the salaried soothsayers) see the Lea Valley: as an open-plan supermarket with a river running through it. The valley is a natural extension of the off-highway retail parks springing up around Waltham Abbey; exploiting the ever-so-slightly poisoned territory yielded by ordnance factories, gunpowder mills, chemical and electrical industries.

The documents put out by the Lee Valley Regional Park Authority dazzle with their high gloss. They confuse weight with importance. Lee Valley Regional Park Plan, Part One: Strategic Policy Framework runs to 180 pages – with charts, illustrations, maps. Statements of intent. Best Value. Whatever turns you on, the Lea Valley has got it. A media-friendly zone (close to Docklands). A recreation zone for Essex Man (easy access to the M25). An eco-zone for butterflies, deer, asylum-seeking birds. The nice thing about no-go, Official-Secrets-Act government establishments is that they are very good for wildlife. Thick woods, screening concrete bunkers and hunchbacked huts from the eyes of the curious, provide an excellent habitat for shy fauna, for monkjacks. During a period when sheep and pigs and cows, all the nursery favourites, were being taken out by snipers and bulldozed into a trench on a Cumbrian airfield, it was gratifying to learn that the threatened musk-beetle is thriving and multiplying in the Lea Valley wetlands. Twenty-one species of dragonfly on a good day. The regional park is a safe haven for grass snake and common toad. The Royal Gunpowder Mills at Waltham Abbey boasts of the largest heronry in Essex and a ‘wildlife watchtower’ with a ‘panoramic view’. The 175-acre site should have opened to the public in spring 2001, but the outbreak of foot and mouth inevitably led to a postponement.

The Lee Valley Regional Park was established in 1967, the year I moved to Hackney. We had slightly different agendas. The Park planners wanted to transform areas of neglect and desolation, the very qualities I was intent on searching out and exploiting. The first argument we had was over the name. I favoured (homage to Izaak Walton) the Lea spelling, where they went for the (William) Burroughs-suggestive Lee. Inspector Lee. Willie Lee. Customised paranoia: double e, narrowed eyes glinting behind heavy-rimmed spectacles. The area alongside the M25, between Enfield Lock and High Beach, Epping Forest, carries another echo of Burroughs: Sewardstone. Seward was his middle name.

The Lea/Lee puzzle is easily solved. The river is the Lea. It rises in a field near Luton, loses its identity to the Lee Navigation, a canal, then reclaims it for the spill into the Thames at Bow Creek. The earlier spelling, in the River Improvement Acts of 1424 and 1430, was ‘Ley’, which is even better. Lea as ley, it always had that feel. A route out. A river track that walked the walker, a wet road. The Lea fed our Hackney dreaming: a water margin. On any morning when the city was squeezing too hard, you could get your hit of rus in urbe. Hackney Marshes giving way to the woodyards of Lea Bridge Road, to Springfield Park; reservoir embankments, scrubby fields with scrubbier horses, pylons, filthy, smoking chimneys.

Without the Lea Valley, East London would be unendurable. Victoria Park, the Lea, the Thames: tame country, old brown gods. They preserve our sanity. The Lea is nicely arranged – walk as far as you like then travel back to Liverpool Street from any one of the rural halts that mark your journey. Railway shadowing river, a fantasy conjunction; together they define an Edwardian sense of excursion, pleasure, time out. Best Value. We, East Londoners, support the Lea, as it supports us, marking our border, shadowing the meridian line. It is enjoyed and endured by fishermen, walkers, cyclists who learn to put up with the barriers, the awkward setts beneath bridges. We pay our tithe.

Sir Patrick Abercrombie’s 1944 Greater London Plan was a visionary document: ‘every piece of land welded into a great regional reservation’. The Lee Valley Recreational Park. A perimeter fence around a Sioux reservation. Compulsory leisure. The Lea would lose its subversive, grubby culture of contraband, villainy, iffy businesses carried out beyond the fold in the map. Way back in 1961, Lou Sherman, Mayor of Hackney, got together with representatives of 17 other local authorities, and with the letterhead support of the Duke of Edinburgh, to realise Abercrombie’s vision. A levy was introduced for councils in Essex, Hertfordshire and London. Grander plans, with the passage of time, required more complex financial structures, ‘partnerships’. Local authorities, national government, Europe: more executive producers than a Dino de Laurentiis epic. The Lea Valley was a future spectacle. Water was the new oil. Housing developments required computer-enhanced riverscapes as a subliminal backdrop.

There would be funds for decontamination, a ‘precept on council tax’, unnoticed, except by readers of the small print. Representatives of 30 boroughs had their places on the council of the Lee Valley Regional Park Authority. Regeneration was the theme, the green lung. A ten-year strategic business plan: ‘It firmly embraces the principles of Best Value in pursuit of enhancements of service delivery.’ Management-speak for the open-air supermarket. Best Value. Never knowingly undersold. Eco-bondage. ‘A unique mosaic of farmland, nature reserves, green open spaces and waterways.’

The Lea, given time and investment, would stand physics on its head. It would become a sylvan alternative to the M25. With the motor-car as its handmaiden. ‘Consideration must be given to the needs of the motorist.’ A green halo. An aureole around smoking tarmac. ‘Leave the M25 at Junction 25. Follow the signs for City. At first set of traffic-lights turn left signposted to Freezywater.’ This is the Lee Valley Leisure Complex. ‘We will make our commitment to our duty of Best Value; ensuring clarity of objectives and customer and performance focus at the heart of our cultural and organisational change . . . Major Capital Development will seek to achieve Best Value.’

On 27 March 1998, I set out to walk up the Lea, from the Millennium Dome on Greenwich peninsula to the M25 in Waltham Abbey, where I would begin an act of counter-magic, a pedestrian circuit of London’s orbital motorway. I was joined by the photographer Marc Atkins and the writer Bill Drummond. Did we qualify as Leisure Park customers? Unlikely. Elective leisure was the condition of our lives, endured through a puritanical work ethic. Drummond scribbling away, anonymously, in the cafeteria of a provincial department store. Atkins hunched in his darkroom. We were spurners of Best Value. Drummond burned money and gave away self-published booklets. Atkins printed more photographs than he could sell in ten lifetimes. I wrote the same book, the same life, over and over again. We wanted Worst Value. We refused cashback. We solicited bad deals, rip-offs, tat. If you explained something to us, we wouldn’t touch it. We knew what Best Value meant: soap bubbles, scented bullshit. That’s why our walk began at the most tainted spot on the map of London. Exorcism, the only game worth the candle.

Gradually, landscape induces confidences. The cycle gates become less of an irritant. Road bridges energise us; traffic noise plays against pastoral tedium. Ferry Lane, Forest Road. On my first walks up the Lea, I used to think that an old fisherman’s pub, here on the fringe of Walthamstow, was truly rustic. Izaak Walton in the back bar stuffing a pike. There must have been a ferry somewhere near this clapboard ghost. A haunt of narrowboat skippers and their dogs. There isn’t much definition in the sky. Pylons and earthworks, water you can’t see. The occasional horse hoping for a handout. I thought of Jock McFadyen’s painting, Horse Lamenting the Invention of the Motor-Car (1985). A blue pantomime beast with a bandaged foreleg on a carpet of wasted turf, surrounded by a stream of toy cars.

Atkins is beginning to limp. This walk is a relatively gentle one, but for some reason – perhaps the monotony of the track, the uneven pebbles – it hurts the unwary. Drummond can’t decide if our expedition is asking the right questions. The land is too anonymous, no major blight, a steady stream of ‘I-Spy’ water fowl. Fish corpses (nothing more exciting than white-bellied carp). I think we can assume that we have penetrated the Lea Valley’s recreational zone. Boats. Wet suits. Easy access to the North Circular Road, the broken link of an earlier orbital fantasy. This border is marked by a permanent pall of thick black smoke. Urban walkers perk up; we’re back in the shit. The noise. The action.

The situation, at the junction of the North Circular and the Lee Valley Trading Estate, is readable. It’s what we are used to, what we advocate; faux Americana, waste disposal, spray from 12-wheeled rigs. Powerhouse, Currys. Mercedes franchise. Signs and signatures. Zany neon calligraphy. Warehouses parasitic on the road, on the notion of movement, easy parking. Old riverside enterprises that basked in obscurity have been forced to come to terms with brutalist tin, container units with ideas above their station. The aesthetic of the North Circular retail park favours colours that play, ironically, with notions of the pastoral: lime green (pond weed), yellow (oil seed rape), blood red. Road names aren’t literary, they’re chemical. Argon Road is a memory trace of Edmonton’s contribution to the manufacture of fluorescent lamps. Light is troubled, unnatural. The scarlet scream of the furniture warehouse fights with the graded slate greys of the road, the river and the sky.

I love it. I like frontiers. Zones that float, unobserved, over other zones. Road-users have no sense of the Lee Navigation, they’re goal-orientated. Going somewhere. Noticing Atkins, foot on barrier, perched in the central reservation, snapping away, drivers in their high cabs see a nuisance, an obstacle. A potential snoop. They’d be happy to run him down. Atkins sees a speedy blur, abstraction, the chimney of London Waste Ltd blasting steam. Visible evil. Pollution from a low-level castle, remaindered gothic. Better and better. The London Waste facility is battleship grey, a colour that is supposed to make it invisible in the prevailing climate: rain, exhaust fumes, collapsed skies. The expectation is that, on an average Edmonton morning, diesel fug and precipitation will disguise the 100-foot tower of the biggest incinerator in Britain. The Waste Zone, that’s one they left out of the brochure. You arrive at the edge of the city, out of sight of Canary Wharf, and you take a dump. Surgical waste, pus, poison, plague. Corruption. All the muck we spew out. It has to go somewhere. Edmonton seems a reasonable choice.

In October 2000, a group of Greenpeace protesters occupied the summit of the burning tower. Gridlock on the M25 is a modest fantasy compared to a blockage in the procedure for the destruction of clinical waste. The Edmonton furnaces dispose of 1800 tonnes of putrid stuff – contaminated bandages, body tissue, dirty nappies, used hypodermic needles – every day. At the time of the protest, waste material was piling up in seven boroughs (Camden, Enfield, Barnet, Hackney, Haringey, Islington, Waltham Forest). Hackney had its own long-running dispute, black bags burst on the streets, as a consequence of the council’s bankruptcy and cutbacks. Generations of braggadocio incompetence, a system built on institutionalised malpractice.

Waste that couldn’t be shipped to Edmonton was transported to landfill sites in Essex and Huntingdon. Convoys took advantage of the M25, which increasingly functioned as an asteroid belt for London’s rubble, the unwanted mess of the building boom, the destruction of tower blocks, the frenzied creation of loft-living units along every waterway.

We’re intrigued by London Waste Ltd and its Edge of Darkness estate. What was once grey belt, the grime circuit inside the green belt, is now called on to explain itself. Before the Lee Valley Regional Park Authority, Euro slush funds and council tax tithes, it didn’t matter. Reclamation was never mentioned. Fish and fowl were there to be hunted. Dirty and dangerous industries provided employment, built cottages for the workers. Now we have Best Value.

The incineration industry, and the London Waste Ltd plant in particular, was investigated by the television journalist Richard Watson for Newsnight. A predictable story of fudging, economy with the truth, buck-passing and ministerial denial. Until August 2000, London Waste was guilty of mixing relatively safe bottom ash with the contaminated fly ash that the process was introduced to burn off and neutralise. The end product was then used in road building, and in the manufacture of the breeze blocks out of which dormitory estates are assembled. Waltham Abbey and its satellites as Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The defoliant Agent Orange, fifty million litres of which were dropped by the Americans on Vietnam, registers around nine hundred nanogrammes of dioxin to one kilogramme of soil. Mixed ash from the incinerators, used on chicken runs in Newcastle, registers 9500 nanogrammes. Eggs concentrated the effect. Combined with the dust, inhaled when householders carry out repairs, hang paintings, drill holes in breeze blocks, they are guaranteed to keep surgeries and hospices busy in the future.

The Environment Agency fed the relevant minister, Michael Meacher, the usual soft soap. The firms responsible for working mixed ash into conglomerates used to surface new roads declined to reveal the locations of their handiwork, the 12,000 tonnes of aggregate dropped on the landscape. Their spokesman, sweating lightly, sported a Buffalo Bill beard: the frontiersman peddling a treaty to the Redskins. One major recipient of this dubious cargo was uncovered by Watson’s researches: the carpark of the Ford plant at Dagenham. The A13, yet again, had something to make it glow at night: a top-dressing of contaminated Edmonton ash. ‘No more dangerous than Guy Fawkes night,’ declared Meacher to the House.

Walking north towards Picketts Lock, we turn our backs on the incinerators, the smoke. Frame it out, it’s not there. Go with the Dufy doodle on the side of London Waste’s rectangular box, the company’s upbeat logo: limpid blue sky, lush grass, a pearl grey building like a Norfolk church. Edmonton is the Inferno and Picketts Lock the garden, the paradise park. In the past, on hot summer walks with my family, we used to come off the Navigation path for a swim at the Picketts Lock Leisure Complex. (How complex can leisure be?) This modest development, on the edge of a hacker’s golf course, was an oasis. It didn’t take itself too seriously and it filled the gap between London Waste’s burning chimney and the Enfield Sewage Works.

The polyfilla theory of Leisure Complex placement, the old treaty between developers, land bandits and improve-the-quality-of-life councillors, worked pretty well. A chlorine-enhanced waterhole on ground nobody could think of any other way to exploit. But that wouldn’t wash in millennial times. The name Picketts Lock began to appear in the broadsheets – and acquired a bright new apostrophe. Pickett’s Lock would be reinvented as a major sports stadium (convenient access to the M25), the venue for the 2005 World Athletics Championships, thereby conferring enormous benefits on the Lea Valley. Tourists, media, retail spin-offs. Computer-generated graphics omitted the chimney at the end of the park, the smoke pall. Nobody was discourteous enough to mention the fact that London Waste had put in an application to extend their site. As we walked north in March 1998, the application still awaited final approval from the Trade and Industry Secretary, Stephen Byers. (Poor man. It was going to get worse, much worse. Byers epitomised the New Labour attitude of glinting defiance; fiercely tonsured and spectacled, tight-lipped, scorched by flashbulbs in the passenger seat of a ministerial limo, assaulted by furry microphones at the garden gate. He would be sideswiped from Trade and Industry to Transport. Picketts Lock to Purgatory. Official pooper-scooper. Ordered to clean up after all those years of misinformation, neglect and underinvestment. Undone by his own spinners and fixers, he came with every new appearance before the media inquisitors to look more and more like a panicked automaton, a top-of-the-range cryogenic model of the Public Servant. Every fulsome non-apology, every linguistic squirm took its toll. Byers enjoyed more premature obituaries than Frank Sinatra; so that his demise, when it came, was barely noticed. Stephen who? Was he the Dome conceptualist who jumped ship? Or the official embodiment of bad news? Status revoked, limo withdrawn, the wretched man was exposed to the ultimate humiliation: a train ride back to his constituents in the North-East. A future as bleak as Middlesbrough.)

When this matter was raised, the site’s owners (Lee Valley Regional Park Authority), became quite huffy, insisting that additional incinerators would ‘pose no risk’ to the health of athletes or spectators. ‘Better by far than Los Angeles in the past and Athens in the future as a venue for the Olympics,’ stated Peter Warren, Lee Valley’s head of corporate marketing.

Lee Valley’s Strategic Business Plan (2000-10) is preparing the ground for change and innovation. ‘The Leisure Centre is an ageing building over 25 years old and the whole complex is subject to emerging, modern competition.’ Horror: ‘25 years old’! Tear it down. The swimming-pool and poolside café might look clean and friendly to the untrained eye, but they are older than Michael Owen. The cinema/video arcade part of the enterprise will remain.

Which is a relief. It is a rather wonderful building, with a long straight approach, a tiled, mosaic walkway. The Alhambra of Enfield. A Moorish paradise of plashing water features, ordered abstraction, glass that reflects the passing clouds. Everything leads the eye to the cinema palace; there is lettering that looks like the announcement of a coming attraction: WELCOME TO LEE VALLEY. The Pickett’s Lock multiplex is one of the wonders of our walk; we begin to understand how a commercial development can be integrated into the constantly shifting, constantly revised aspect of the Lea Valley. With its strategic use of dark glass and white panels, the generous space allowed between constituent elements in the overall design, Pickett’s Lock presents itself as a retreat, a respite from the journey. Buffered by the golf course, it remains hidden from the Navigation path. But, should you take the trouble to search it out, here is green water (swimming-pool, ponds and basins); here is refreshment (motorway standard nosh, machine-dispensed coffee froth); here are public areas in which to sit and rest and study maps.

Pickett’s Lock works best, as a concept, if you don’t step inside, if you avoid the full Americana of burger reek (foot-and-mouth barbecues with optional ketchup), popcorn buckets, arcade games in which you can attack the M25 as a virtual reality circuit. UP TO TWO PLAYERS MAY RACE AT ONCE. INSERT COINS. In fact, this sideshow at Pickett’s Lock represents the Best Value future for the motorway: grass it over and let would-be helldrivers take out their aggression on the machines.

This pleasing sense of being removed from the action, the imposed-from-above imperatives, that we must enjoy ourselves, take healthy (circular) walks, observe bittern and butterfly, nod sagely over the ghosts of our industrial heritage, is fleeting. The builders, earth-movers, JCBs, will soon be rolling in: hacking up meadows to make way for another stadium, another crowd-puller; more promised, postponed pleasure. Postponed indefinitely. New Labour couldn’t face another Dome. Another money pit. They waited for Bad News Day, 11 September 2001. Then slipped the announcement into the small print. The Pickett’s Lock athletic stadium was aborted. No mention of London Waste. Economic considerations only. The apostrophe was withdrawn like Princess Di’s royal status. Picketts Lock, now surrounded by an ever-expanding retail park with suspiciously bright roads, could go back to being a community centre for a community of transients.

Why, I wondered, as we hit the stretch from Ponders End to Enfield Lock, were there no other walkers? As a Best Value attempt at drumming up clients for their recreational facilities, the Lee Valley marketing men were not having a good day. Most people who live for any length of time in East London, even Notting Hill journalists with friends in Clapton or connections in Hoxton, claim to walk the Lea. Filter beds, Springfield Park Marina, Waltham Abbey – they boast of an intimate knowledge. Any free moment, there they are, out in the fresh air, hammering north. But the towpath stays empty. A few dog-walkers, the odd short-haul cyclist. Where are the professionals, the psychogeographers, note-takers who produce guides to ‘The London Loop’ or ‘The Green Way’? Local historians uncovering our industrial heritage: do they work at night?

We’re on our own, exposed; under a cradle of sagging wires in a pylon avenue, on a red path. Marc’s foot is swollen and he’s beginning to lag behind. Drummond is still buzzing; logging blackthorn blossom and airing his obsession with the Unabomber. We noticed rusted sculptures that should have been milestones. They’d been sponsored and delivered, but they didn’t belong. ‘Art,’ I muttered. ‘Watch out.’ Objects that draw attention to themselves signal trouble. We were walking into an area that wanted to disguise its true identity, deflect attention from its hot core.

The Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock is an island colony, once enclosed, independent, now up for grabs. It’s surrounded by water, so it has to be desirable real estate. The Italianate water tower, or clock tower, will be preserved, and the low barracks transformed into first-time flats, housing stock. The nature of government land, out on the perimeter, changes. Originally, work was life, work was freedom (the cobbled causeway running towards what looks like a guard tower triggers an authentic concentration camp frisson); now work is secondary, it takes place elsewhere. Sleeping quarters have become the principal industry. Compulsory leisure again. The factory revealed as a hive of non-functional balconies, satellite dishes monitoring dead water.

Enfield Lock is imperialist. It has signed the Official Secrets Act – in blood. A scaled-down version of Netley, the Royal Victoria Military Hospital on Southampton Water. Hospitals, ordnance, living quarters: the same pitch, the same hollow grandiloquence. If you come east from the town of Enfield, from the station at Turkey Street, you march down Ordnance Road. This was the route John Clare took, travelling in the other direction, when he walked away from the High Beach madhouse in Epping Forest. Powder-burns on privet. Suburban avenues, lacking pedestrians, with front gardens just big enough to take a parked car. Vandalised vehicles, cannibalised for spare parts, stay out on the street. There’s not much rubbish, no graffiti. Military rule is still in place.

The Royal Small Arms Factory was a Victorian establishment, post-Napoleonic Wars. Private traders couldn’t produce the quantity of guns required to maintain a global empire. The cottages of Enfield Lock were built to house workers from the machine rooms and grinding mills. The River Lea was the energy source, driving two cast-iron water-wheels. The small country town on the Essex/Middlesex border gave its name to the magazine rifle familiar to generations of cadet forces, training and reserve battalions: the Lee Enfield (‘Lee’ is just a coincidence – James Paris Lee was the rifle’s designer). This multiple-round, bolt-action rifle, accurate to 600 metres, was the most famous product of the Enfield Lock factory, the brand leader. In the First World War it was known as the ‘soldier’s friend’. The factory survived until 1987, to be replaced by what promotional material describes as ‘a stylish residential village’.

The developers, Fairview, take a relaxed view of the past. ‘New’ is a very flexible term. ENFIELD ISLAND VILLAGE, AN EXCITING NEW VILLAGE COMMUNITY. A captured fort. A workers’ colony for commuters who no longer have to live on site. The village isn’t new, the community isn’t new, the island isn’t new. What’s new is the tariff, the mortgage, the terms of the social contract. What’s new is that industrial debris is suddenly ‘stylish’. The Fairview panoramic drawing, removed from its hoarding, could illustrate a treatise on prison reform: a central tower and a never-ending length of yellow brick with mean window slits. If you knew nothing about the Small Arms Factory, and were wandering innocently along the towpath, you’d pick up the message: keep going. Government Road. Private Road. Barrier Ahead. The pub, Rifles, must be doing well; it has a carpark the size of the Ford Motor Plant at Dagenham. Rifles isn’t somewhere you’d drop into on a whim. The black plastic awning features weaponry in white silhouette, guns crossed like pirate bones. TRAVELLER NOT WELCOME. ‘Which traveller?’ I wondered. Has word of our excursion filtered down the Lea? OVER 21s. SMART DRESS ONLY. Is it the migratory aspect that these Enfield islanders object to? Or the clothes? What were they expecting – red kerchiefs, broad leather belts, moleskin waistcoats?

Whatever it is they don’t like, we’ve got it. No Public Right of Way. Footpaths, breaking towards the forest, have been closed off. You are obliged to stick to the Lee Navigation, the contaminated ash conglomerate. Enfield has been laid out in grids: long straight roads, railways, fortified blocks. Do they know something we don’t? Are they expecting an invasion from the forest? Enfield Lock has an embargo on courtesy. In a canalside pub, they deny all knowledge of the old track. Who walks? ‘There used to be a road,’ they admit. It’s been swallowed up in this new development, Enfield Island Village. ‘Village’ is the giveaway. Village is the sweetener that converts a toxic dump into a slumber colony. You can live within half an hour of Liverpool Street Station and be in a village. With CCTV, secure parking and uniformed guards.

The hard-hat mercenaries of Fairview New Homes plc are suspicious of our cameras. Hands cover faces. Earth-movers rumble straight at us. A call for instruction muttered into their lapels: ‘Strangers. Travellers.’ The FIND YOUR WAY AROUND ENFIELD ISLAND VILLAGE map doesn’t help. Interesting features are labelled ‘Future Phase’. You’d have to be a time-traveller to make sense of it. A progression of waterways like an aerial view of Venice. YOU ARE HERE. If you’re reading this notice, you’re fucked. That’s the message.

‘Building on toxic timebomb estate must be halted,’ the Evening Standard said (12 January 2000). ‘A report published today calls for an immediate halt to a flagship 1300-home housing development on heavily polluted land at the former Royal Small Arms Factory, Enfield Lock.’ The drift of the piece is that the Enfield Lock scheme is the model for the decontamination of a series of other brownfield sites, worked-out sheds, shacks and bunkers that once operated alongside London’s rivers and canals. A cosmetic scrape at the topsoil, a capping of the lower levels, wouldn’t do.

An attitude of mind that found its apotheosis in the Millennium Dome was evident throughout New Labour’s remapping of the outer belts, the ex-suburbs. Nobody can afford to live at the heart of the city unless they are part of the money market (or its parasitic forms). The City of London is therefore the first Island Village; sealed off, protected, with its own security. Middle-grade workers and service industry Transit van operatives will be pushed out towards the motorway fringes. The hollow centre will then be divided up: solid industrial stock, warehouses and lofts, will go to high-income players (City, media); Georgian properties (formerly multiply occupied) will recover their original status (and double as film sets for costume dramas); jerry-built estates will go to the disenfranchised underclass, junkies and asylum seekers.

Unsafe as Houses: Urban Renaissance or Toxic Timebomb? Exposing the methods and means of building Britain’s homes on contaminated land, a report commissioned by Friends of the Earth and the Enfield Lock Action Group Association, revealed that planning permission had been granted before questions about contamination had been resolved. Planning permission was in fact granted on the basis of information supplied by the developers. Enfield Council’s chief planning officer, Martin Jarvis, stepped down from that role. He soon found a new position: as a director of Fairview Homes. He was among familiar faces. His son also worked for Fairview, as did the daughter of Richard Course, chairman of the council’s environment committee.

Now our goal is in sight, beyond Rammey Marsh, traffic floating above water. Site clearance (leisure, commerce, heritage) pushes the horizon back. ‘A new country park is to be developed on the site of the former Royal Ordnance works,’ the Lee Valley Regional Park Authority’s Strategic Business Plan announces. ‘The site is immediately to the south of the M25, adjacent to major housing developments and strategically ideal for the Authority to pursue its remit to safeguard and expand the “Green Wedge” into London.’

This sounds like an uncomfortable procedure. Not just ‘soil amelioration’ and ‘imaginative and sensitive landscape design’, but the effort of will to rebrand a balding and sullen interzone, the motorway’s sandtrap, as a wildlife habitat, ‘a vibrant waterside park’. For years, Waltham Abbey has functioned like a putting course, a splash of shaved meadow surrounded by bunkers. It was a course that had to be played with blindfold firmly in place. Much of the territory was unlisted. Government Research Establishment to the east of the Navigation, Sewage Works (Sludge Disposal) to the west.

In this red desert, soundwaves move from margin to margin: caterpillar-wheeled vehicles, mud gobblers, chainsaws, pneumatic drills. The delirious swooshing of the M25. The bridge support, the thin line that carries all this traffic, is pale blue. The space beneath the bridge expands into a concrete cathedral, doors thrown open to light and landscape. Water transport gives way to road; the old loading bays are empty, a few pleasure boats and converted narrow boats are tied up against the east bank. Reflected light shivers on pale walls. Overhead, there is the constant thupp-thupp-thupp of the motorway. After heavy rain, the ground is puddled and boggy. Travellers haven’t settled here. The evidence is all of migration: extinguished fires, industrial-strength lager cans, aerosol messages.

Bill Drummond leads the rush up the embankment. The M25, after miles of walking the ditch, is a symbol of freedom. The Amazon. A slithery, ice-silver road in the sky. After a sharp climb, a fence hop, slipping on gravel and thin wet grass, Drummond reaches the roadside. He vaults the low barrier and performs a Calvinist version of the Papal kiss. He puts his lips to tarmac, tastes the vibration of the orbiting traffic.

Sitting on the crash barrier, feet dangling on the sand-coloured hard shoulder, we are buffeted by backdraught: the road is a blur. Clockwise: Waltham Abbey and the forest. Anticlockwise: Paradise. A chocolate brown notice: PARADISE WILDLIFE PARK. A Lascaux sketch of stag’s horns, an arrow. A shamanic invitation to the country of parks and gardens and paradises. Cars are streaming into the sunset, brake-lights bloody. Drummond wants to walk straight off down the road, west. A truck swerves and honks. I have to grab him, persuade him that I don’t intend to stay, dodging lorries in the half-dark, on the metal skin of the M25. That would be blasphemous. I’m going to stick to the countryside, as near as I can to the loop, straining to catch the hymn of traffic, hot diesel winds.

The road at night is a joy. You want to imagine it from space, a jewelled belt. As a thing of spirit, it works. As a vision, it inspires. There is only one flaw: you can’t use it. Shift from observer to client and the conceit falls apart. Follow the signs for LONDON ORBITAL and consciousness takes a dive. The M25 has been conceived as an endurance test, a reason for staying at home. Aversion therapy. Attempt the full circuit and you’ll never drive again.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.