The Brighton Museum is open again. Ten million pounds has been well spent: it is tidier, lighter, more extensive and more coherent than it was. The rich, crammed display style, which always suited its heterogeneous holdings, has been brought up to date rather than abandoned for something cooler.

Brighton life joins hands with what the museum shows. People come festively to the seaside. They display their bodies. Those who pierce, decorate and tattoo find an unusually high proportion of others who do the same. They often dress garishly, tribally and inventively. So the Museum’s displays under the heading ‘Body’ (subsections: ‘skin’, ‘hair’ and ‘flesh’; sub-subsections: ‘binding’, ‘cutting’ and ‘enlarging’) and those under ‘Fashion and Style’, which show fashion-driven items from the Prince Regent’s own dressing-gown to shoes by Jimmy Choo and an outfit by Issey Miyake, are all interestingly close to the life of the town.

Similarly, ‘World Art’ – drawn from the fifteen thousand items in the Museum’s ethnographical collection – seems both less exotic and more relevant than it might elsewhere. The dust of the traveller’s trophy room is not entirely absent: among people specifically celebrated are F.W. Lucas (1842-1932), a local collector of objects made from human and animal remains, and Melton Prior (1845-1910), who brought home trophies and weapons from the places he visited as war correspondent for the Illustrated London News. But many of the masks, totems and costumes found their original use in ceremonies and festivals which, one realises looking at them here, are not so very far from pier-end entertainments.

The Museum stands as commentator on, and critic of, a shameless building – the Pavilion, of which it is a part. The Pavilion’s design is more window-dressing than architecture; its furniture is not gentlemanly; its decoration cocks a snook at good taste. The Museum’s collection of furniture, glass and pretty things shows how later smart sets also furnished to tease and decorated to stun. This is not the history of modern design that begins with Pevsner’s pioneers and ends with Ikea. From Art Nouveau sinuosity via Art Deco smartness and Surreal cheek (the Mae West lips sofa) to pieces by Starke and Gehry, there is more of the glitz of 1930s film sets and the comic-book future of science fiction movies than the Good Design of corporate headquarters.

Free associate on ‘stucco’ and you get ‘peeling’. The charm of Brighton cannot be separated from its combination of brilliance and decay. Seaside salt wind is hard on its façades; its weather-beaten face is always in need of another coat of slap. (In Brighton scaffolding is in such demand that it goes on from job to job and never gets back to the yard.) But even the brightest of its terraces are admonished for their flightiness by stern brick churches. The tall box of St Bartholemew (Edmund Scott, 1874), which rises grandly above the poor streets that fill the valley below the station, is one of the best and most original of all Victorian churches. St Michael and All Angels is almost as impressive. It has a complicated building history: Bodley was responsible for the first church of 1858, Burges designed the additions which were completed by 1893. Its high, black and red brick walls frown darkly on the frivolity of the pretty, balconied houses below. People, it turns out, didn’t always come to the seaside for fun. But seriousness has many flavours. Among the collections which have come to the Museum one of the most curious and interesting, the ‘popular pottery’ given by Henry Willett in 1903, is presented as social history. Willett’s intention was to educate the public and with this in view he stipulated that his own categories be kept: ‘Naval Heroes’, ‘Royalty and Loyalty’, ‘Domestic Incidents’ and so on. The late 18th and early 19th-century pieces combine classically simple shapes with crude or quaint painted and transferred images: this combination of the raucous and the elegant is also very Brighton.

Provincial museums, if they are lucky, juxtapose a handful of very good pictures with more ordinary, often local paintings. This has its advantages. You look at the best more carefully and at pictures with local connections with more intelligent curiosity. Quite ordinary pictures of known places give pleasure in a way better ones of unknown places do not. Ruskin Spear’s Sickert-like picture of deckchair, shingle and sea, which is a minor painting, is an excellent stimulant to memory. Among the Victorian paintings are a couple by Alma-Tadema which, as Sickert put it, show what a cultured and learned gentleman who lived in St John’s Wood thought the Romans and Egyptians were like. But although they do say more interesting things about St John’s Wood than about Rome, they are confected from such an absurdly clever repertoire of surface representations – fur, marble, cheeks, chiffon and so on – that you are able to see them as a compliment to the Brighton of little antique shops: a town that loves things. The big Edward Lear landscape may not be as brisk and decisive as his watercolour sketches, but it’s only fair to take his own preferences seriously once in a while. Pictures – certainly the pictures here – were, on the whole, made for middle-class walls. Solid, churchgoing Brighton, too, has its say.

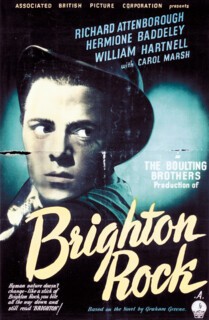

Smart crescents and squares, antique shops, grand hotels, the list of people who have retired here: such things contribute very little to Brighton as it exists in the popular imagination. The first special exhibition in the redeveloped Museum is a very good one about Brighton in the movies (Kiss and Kill, until 1 September). Here different Brightons – vulgar postcard Brighton (Carry on at Your Convenience), louche Brighton (The First Gentleman, The Gay Divorcee), the Brighton of the disaffected young (Quadrophenia) and the Brighton that mixes violence and fairground glitter (Brighton Rock, Oh! What a Lovely War) – are extracted as simple essences from the mix that is the town itself.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.