John Berger’s selected essays run to nearly six hundred pages, yet that is just the tip of the iceberg if one looks at the totality of his published work: the essays and reviews about the visual arts – drawing, painting, photography, film – but also short stories, journals, screenplays, travel articles, letters, television scripts, translations, novels, poems, even a requiem in three parts which gives a wrenching account of the untimely deaths of three of Berger’s neighbours. From 1951 to 1961 he wrote reviews for the New Statesman, and subsequently published regularly in New Society, as well as New Left Review, the Observer, the Sunday Times Magazine, Marxism Today, Réalités, the Village Voice, Harpers, Granta, Expressen, El País and 7 Days. It is a daunting task to find some way of coming to terms with such a rich and extensive body of work, all of it marked by Berger’s unflagging seriousness, his insistence on somehow merging personal response, social insight, aesthetic theory and political commentary. Every piece is rigorously thought through but also heartfelt, sometimes almost embarrassingly so.

Berger’s reputation is that of a political radical, a romantic Marxist, a sympathiser with the underdog and the lonely rebel, a social critic and an outspoken castigator of market values – especially art market values – and of a predatory capitalism. Yet he is also obsessed by the past, even by the distant past – at times he is a romantic, at times a classicist. On occasion he has the appearance of a stubborn conservative, disregarding or brusquely dismissing new trends and new fashions. I anticipated positive references to Millet, Courbet, Cézanne and Van Gogh, but I was surprised to find how seriously artists such as Piero della Francesca, Dürer, Grünewald, Hals, Rembrandt, Poussin, Watteau or Goya are presented as templates for great art, today as in the past.

Impressionism, Cubism and Constructivism are celebrated, too, but Berger shows little interest in Surrealism, Art Brut, Abstract Expressionism, Assemblage, Pop Art, Conceptualism or other recent trends, and can be quite contemptuous of all of them. The 20th-century masters he praises most highly are Picasso and Léger – both Communist Party members. Léger, in particular, is a ‘heroic’ artist, who ‘rejected every implication of “Glamour”’. Eventually, however, Berger appears to have become disenchanted with Communism as a form of state power. ‘Early Constructivist’ works, made in the first flush of Revolutionary enthusiasm, expressed ‘the hopes aroused by the new functional possibilities of science and engineering for an industrially backward country in a time of revolution’ – hopes which were soon to be dashed. In a similar vein, Berger wrote a book about the dissident Russian sculptor Ernst Neizvestny, whose work was publicly denounced by Khrushchev and who subsequently emigrated to the West, just as Naum Gabo had emigrated many decades before. In each case, Berger expresses sympathy for both the artist’s work and his plight, yet also feels that his art deteriorated when he had to function within a market economy.

As time went by, Berger clearly began to broaden his understanding of Marxism. By the 1970s he is writing in New Society about Victor Serge and Walter Benjamin, independent Marxists who were opposed to the Party line or idiosyncratic in their interpretation of Marxist theory. Serge was a former anarchist who was soon expelled from the Party and ended up as a ‘left oppositionist’, disenchanted with Stalinism and turning towards Trotskyism. His novel Birth of Our Power, about which Berger writes eloquently, was set in 1917 in Barcelona, where the novel’s protagonists ‘had a quiet little room with four cots, the walls papered with maps, a table loaded with books. There were always a few of us there, poring over the endlessly annotated, commented, summarised texts. There Saint-Just, Robespierre, Jacques Roux, Babeuf, Blanqui, Bakunin were spoken of as if they had just come down to take a stroll under the trees.’ They were also optimists. As an Italian anarchist put it, ‘the hour is not far distant when a new sun will shine on all men alike.’ Cubism, too, was warmed by this new sun.

I suspect that Berger himself had read many of the same books, from the same canon of French revolutionary literature. He respected David as a painter because of his ‘revolutionary classicism’ and, in his book on The Success and Failure of Picasso, he cites Bakunin’s typically anarchist dictum that ‘the urge to destroy is also a creative urge,’ comparing it to Picasso’s observation that ‘a painting is a sum of destructions.’ Picasso’s formative years were spent in Barcelona, a city Berger characterises as lawless, violent and extreme in its politics. He goes on to connect Picasso’s central role in the development of Cubism to his experiences in Catalunya. It was Barcelona that gave him the energy to create ‘a revolution in art’, as Berger characterises Cubism, a revolution which abruptly ‘changed the nature of the relationships between the painted image and reality’. This revolution in art, moreover, was provoked by Picasso’s own ‘insurrection’, as embodied in the Demoiselles d’Avignon, a painting inspired by his memories of Barcelona. The Cubist painters, Berger concludes, ‘did not think in political terms. Yet they were concerned with a revolutionary transformation of the world.’

Cubism, however, ‘was only a beginning, and a beginning cut short’. The ‘post-Cubist art’ which followed no longer ‘reflected the possibility of a transformed world’, as Berger laments, but instead tended to be ‘anxious and highly subjective’. Within the category of post-Cubist art, Berger groups together Dadaism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism and, more precisely, the work of Chirico, Miró, Klee, Dubuffet and even Picasso: the Picasso of the 1920s and early 1930s, before his work was reinvigorated by hostility to the Franco regime and Fascism in general, before he was able to paint Guernica; and, subsequently, the postwar Picasso, whose work became schematic and sentimentalised. Berger was surely right to place the development of Cubism within a political and social context. Unfortunately, his fixation with it as the one valid art movement eventually led him into an impasse. If Cubism had failed, what hope was there of further success?

This question was particularly acute during the late 1940s and early 1950s, when Berger was active in the Artists International Association (AIA), a grouping founded in 1933 by British artists who shared a broadly socialist agenda, eventually focused on the struggle against Fascism – in Spain and then, with the rise of Nazism and the onset of war, throughout most of Europe. After the war the AIA divided, basically between pro and anti-Soviet wings, or, in more general terms, between an increasingly politicised and an increasingly depoliticised wing. Berger, at that time, was actively engaged with the more politicised tendency. It was not long, however, before Soviet condemnation of Modernism in art exacerbated the split still further. In August 1950, Berger exhibited his own work under the aegis of the AIA. His subjects, the Manchester Guardian noted, included ‘fishermen, oxyacetylene welders, builders and – shades of Léger – acrobats’. He was now in his early twenties. Educated at private schools, he had studied at the Central School of Art, after which he was drafted into the Army, where he encountered working-class men for the first time. Demobilised, he taught art for the Workers’ Educational Association, and painted in his spare time.

During this same period, Berger began to review British painting intensively. In his first collection of essays, Permanent Red, he divided artists into those who are ‘defeated by the difficulties’ of being an artist and ‘Artists who struggle’. The first category included Barbara Hepworth (the only female British artist Berger reviewed during this period) alongside John Bratby and a number of prominent foreigners – Gabo, Klee, Pollock, Dubuffet and Germaine Richier among them. The second, more positive category included Henry Moore, Ceri Richards, William Roberts, Josef Herman, David Bomberg, L.S. Lowry, George Fullard and Frank Auerbach, together with the Dutchman Friso ten Holt. Of these, only the enthusiastic review of Lowry is included in the new collection, which is overwhelmingly dominated by French-based artists.

Francis Bacon, whose work Berger reviewed in the New Statesman early in 1952, has also been included, however. Recognised by Berger as a painter of extraordinary skill, he is nonetheless demeaned by an odd comparison with Walt Disney. Berger sees both Bacon and Disney as creating mindless worlds ‘charged with vain violence’, a similarity enhanced by ‘the surprising formal similarities of their work – the way limbs are distorted, the overall shapes of bodies, the relation of figures to the background and to one another, the use of neat tailor’s clothes, the gestures of hands, the range of colours used’. The two artists, Berger decides, reacted in similar ways to a pessimistic vision of the fate of humanity in a world that held out no hope of improvement, an alienated world in which mindlessness has become inevitable.

In 1951, the year of the Festival of Britain, the art world had been marked by considerable controversy, particularly in relation to the Arts Council’s travelling exhibition, 60 Paintings for ‘51, centring on William Gear’s large abstract painting, Autumn Landscape, and Berger, always pugnacious, was quickly drawn into the fray. The editors of the Studio published a commentary on the exhibition, under the title ‘Art without Faith’, lamenting that ‘the world as seen by the so-called “modern” painter and sculptor is a synthetic, cynical world; a world of psychoanalysts and materialists morbidly interested in the odds against wholesale destruction and manoeuvres for material gain.’ It would be wrong to link Berger to this kind of attack but it is nonetheless true that, at that moment in his career, he was disposed to dismiss abstract painting as a blind alley. He was, for example, less than welcoming to Gear, a painter who already enjoyed an international reputation. In 1948, Gear, then based in Paris, had exhibited with Réalités Nouvelles and, along with Stephen Gilbert, had also become one of only two British founding members of the CoBrA group, whose significance has been aptly characterised by Chris van der Heijden: ‘in the midst of the darkness of the Cold War the colours of CoBrA take on a special significance – that of intensity, anger, desire and simplicity.’ In 1949, Gear’s work was exhibited alongside Jackson Pollock’s at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York. In other words, Gear was part of a large international movement.

Berger remained suspicious of this whole trend, which he felt was symptomatic of what he considered ‘a period of cultural disintegration’. In this context, it is interesting to read his reviews of Pollock, written for the New Statesman in 1951 and 1958. He notes that Pollock was influenced by the Mexicans – especially by Siqueiros, a dyed-in-the-wool Stalinist who led a murderous attack on Trotsky – and by Picasso, who was simply a well-meaning Party member. He also observes that Pollock was highly talented, indeed ‘a most fastidious, sensitive and “charming” craftsman, with more affinities with an artist like Beardsley than with a raging iconoclast’. The daring comparison with Beardsley surprised me, although I suppose it’s no more mind-boggling than his comparison of Bacon’s distortions with Disney’s. I should add that Berger also described Pollock as ‘a little like James Dean’, at least in his penchant for acting dumb. Insofar as he was able to praise Pollock at all, Berger saw his work as a response to ‘the decadence of the culture to which he belongs’, asserting that ‘his talent will only reveal negatively but unusually vividly the nature and extent of that decadence.’

The question which immediately suggests itself is: ‘What then would be a positive response to that decadence?’ It’s not quite clear how Berger might have answered. He seems to have favoured qualities such as discipline, control and organisation, expressing a nostalgia for Mondrian as the last positive and successful abstract artist. On the whole, however, he turns towards realism: not ‘Socialist Realism’ as such but a sober realism which expresses a sense of vigour and hope and a refusal to submit to the changing tastes of the art world. Soon after his critical articles on Pollock, Dubuffet and Tachisme, Berger was busy praising Friso ten Holt, whose work he hoped might lead to a belated restoration of the faltering Cubist regime:

the path he has chosen is one of the most difficult an artist can choose today . . . It is the path which leads from a complete understanding of the laboratory experiments of 20th-century art forwards towards their application to life. It avoids romanticism. Its aim is objectivity, but not naturalism. Its spirit is rational. Its faith is in art itself and yet it is entirely opposed to art for art’s sake.

This is as close as Berger ever comes to expressing an emphatic personal credo. Soon afterwards, he decided to leave England for good and moved to France. Not surprisingly, this abrupt change led to a dramatic shift in his thinking about art. He was no longer confined within the small world of British taste, a world still dominated by Bloomsbury, on the one hand, and Herbert Read, on the other. He had become a migrant, a role he cherished. Even more important, he now chose to live in the remote countryside. Emphasis begins to shift away from the worker, in the classical Marxist sense, to the peasant, and with this change comes a reassessment. The art of the past begins to seem more significant than that of the present. In 1970, he wrote an essay for New Society called ‘The Past Seen from a Possible Future’, which seems to sum up his change of attitude and approach. In it, he noted that the great tradition of painting – a steady forward movement from Renaissance to Baroque to Mannerist to Neoclassical, a movement which began with Van Eyck and ended with Ingres – began to disintegrate with the onset of the epoch we now think of as ‘modernity’.

Within that lost tradition there were paintings which, as Berger explained, ‘transcend the tradition to which they belong’, though the tradition had also been quite artificial, governed by rigid rules of perspective and composition. Delacroix, he notes, was ‘the first painter to suspect some of what the tradition of the easel picture entailed. Later, other artists questioned the tradition and opposed it more violently. Cézanne quietly destroyed it from within.’ After Cézanne, of course, came Cubism and the great breakthrough. Easel painting survived but, as it began to falter, Berger first rallied to its defence and then abandoned it, not for a new advance in painting, but by turning instead towards photography. Here his reading of Benjamin played a crucial role, but so did his growing recognition that photography presented a new challenge to the tradition of painting. Not only was it intrinsically realist: it had largely escaped the reach of the art market. Photographs could be commodified – and were – but, for the most part, they circulated outside the market. They were kept in a drawer or an album rather than displayed. Once again his focus changed.

By now he had become acclimatised not only to France but also to the peasant culture of the Alpine village where he had lived since 1974. More and more, the peasantry became his central focus. The continuity of their history and traditions was unbroken, to a degree closed off from the urban culture which increasingly dominated the world, with its project of perpetual change and renewal. England had long ago discarded the last traces of peasant culture: there were farmers, but farming had itself become an industry, fully mechanised and intimately linked to massive food companies. In his 1979 novel, Pig Earth, he took on the role of one of those traditional village storytellers who, in his own words, were an ‘organic part of the life of the village’. The villagers enjoy the tales they are told by ‘the man who has stayed at home, making an honest living, and who knows the local tales and traditions’.

Not surprisingly, the artists who now occupied his attention included Millet and Van Gogh, painters about whom he had first written in 1956, when he took care to distance himself from Millet’s religiosity while observing that he

was a moralist in the only way that a great artist can be: by the power of identification with his subjects. He chose to paint peasants because he was one, and because . . . he instinctively hated the false elegance of the beau monde. His genius was the result of the fact that, choosing to paint physical labour, he had the passionate, highly sensuous and sexual temperament that could lead him to intense physical identification

– a description which immediately suggests that Berger saw in Millet a version of himself, the Berger who wrote so intensely about sex in his stories and novels. On the other hand, as he pointed out in 1976, ‘among Millet’s paintings are the following experiences: scything, sheep shearing, splitting wood, potato lifting, digging, shepherding, manuring, pruning. Most of the jobs are seasonal, and so their experience includes the experience of a particular kind of weather.’

The key concept here, I think, is the idea of a subject’s own ‘experience’ as the core value of a painting, or of a lifetime of painting. The particular experience in Millet’s case, that of the peasant, had not been painted before. The peasantry’s life was primarily one of penury as, freed from feudal servitude, they were thrown onto the free market and, consequently, ravaged by capitalism. Berger also notes, pointedly, that however conservative Millet’s perspective may have been, he nonetheless foresaw that ‘the market created by industrialisation, to which the peasantry was being sacrificed, might one day entail the loss of all sense of history. This is why for Millet the peasant came to stand for man, and why he saw his paintings as having a historic function.’ The phrase ‘having a historic function’ assigns painting a practical rather than an aesthetic value. It suggests that paintings can set us thinking about the changing context of our own lives, about our subordination to the contemporaneity of breaking news and our forgetfulness of the past, forgetfulness even of our own life experience.

Reading Berger on Millet, I began to think about Dubuffet. At first sight few painters could be more different. Millet was revered by Berger, Dubuffet was dismissed as a scrawler, an artist who ‘communicates nothing’, a man who ‘apes the inarticulate and disoriented victims of his own society – those who are driven by loneliness and frustration to draw primitively their private obsessions on public walls’. Perhaps the Berger of today might be kinder and gentler towards Dubuffet, less brutally dismissive both of him and of ‘primitivism’ in general. As an admirer of Dubuffet, I thought about the things he had said about his own work: his wish that people would look at it ‘as an enterprise for the rehabilitation of scorned values’ and about his experience of working on his rural series, Cows, Grass, Foliage. In July 1954, Dubuffet’s wife had moved to the country, for health reasons, and Dubuffet followed her, setting up a small studio in the village. There, he recalls, ‘I became preoccupied with country subjects: fields, trees, grassy pastures, cattle, carts and the work of the fields.’ Three years later, he embarked on a series of paintings of the soil itself: The Voice of the Soil and Person Attached to the Soil – works in which texture was more important than form or colour, verging on the ‘primitive’ but without any kind of condescension.

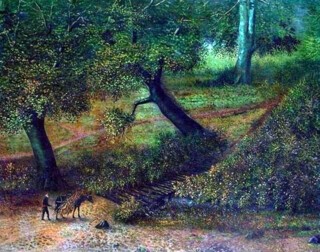

The grotesque aspects of Dubuffet’s work are much less alarming to me than the flirtation with Heidegger on which Berger now embarked. Strangely, the review which marked his turn towards Heidegger was of a work painted in the late 19th century by a Turkish artist, Seker Ahmet Pasa. Seker Ahmet had lived in Paris where, according to Berger, ‘he was strongly influenced by Courbet and the Barbizon School.’ The painting which so impressed Berger was called Woodcutter in the Forest, but despite its fascination for him, he was troubled by an apparent inconsistency in its treatment of space. The position of the woodcutter, Berger noted, could be interpreted in two contradictory ways, perhaps because the painter had been caught between two conflicting schools of landscape painting, Turkish and French. Berger was still wondering about this strange painting, with its disjuncture between different artistic traditions, when he came across Heidegger’s ‘Conversation on a Country Path about Thinking’ and began to meditate on the Heideggerian concept of the ‘coming-into-the-nearness of distance’. Heidegger, he felt, would have been tempted to write about this painting, even though he had clearly been committed to classicism in the arts.

I must confess my own deep antipathy to Heidegger, an antipathy I feel not only because of his pro-Nazi past but also because of the political implications of his later philosophical writings. Berger, to my surprise, turns out to be uncritically enthusiastic about Heidegger, to whom he had been introduced by George Steiner’s book in the Fontana Modern Masters series. Berger recalls how Heidegger, whose father was a carpenter, continually used the forest as a symbol of reality, explaining that ‘the task of philosophy is to find the Weg, the woodcutter’s path, through the forest. The path may lead to the Lichtung, the clearing whose very space, open to the light and vision, is the most surprising thing about existence, and is the very condition of Being.’ In this context, he interprets Seker Ahmet’s painting as being about the ‘coming-into-the-nearness of distance’. Berger notes that he could think of no other painting of which this was so clearly true, adding, for good measure, that ‘implicitly the work of Cézanne is very close to Heidegger’s vision, which is perhaps why Merleau-Ponty, a follower of Heidegger, understood him so deeply.’

Berger’s uncritical acceptance of Heidegger is disconcerting, especially in the context of his intense interest in peasant life, but I very much welcome his enthusiasm for Seker Ahmet’s painting, a work which clearly fell outside the European canon. Some years earlier, in 1955, Berger had also praised the work of the Indonesian painter, Affandi, whose ‘romantic but outward-facing expressionism’ might be ‘the natural style of art for previously exploited nations fighting for independence’, whereas a modern industrial society would be more likely to favour some form of classicism. He also wrote in the New Statesman about artists from Latin America, India, Africa, Sri Lanka and China, as well as expressing his hope that Picasso’s interest in African art might inspire a new generation of African artists to value their own artistic traditions. His internationalism prompted him to give away half of the Booker Prize money awarded to him for his novel G, handing it over to a group of Black Panthers who, he hoped, might use it to put an end to the exploitation of Guyana by Booker McConnell, the award’s sponsors.

Nonetheless, Berger’s main concern remained with European artists – not only with his own contemporaries, but also the Old Masters. Already, in the 1950s, he was writing copiously about a wide range of artists from Chardin to Rembrandt (by far the most frequently), Rubens, Signorelli, Stubbs, Titian, Turner, Van Eyck, Velázquez, Veronese, Vouet and Watteau. Often they were discussed in direct comparison with a contemporary artist whose work interested him. Thus Picasso was compared to Goya, in respect to their drawings, or Kokoschka to Rubens, in respect to their temperaments. Eventually, in 1972, Berger attacked conventional art history head on in Ways of Seeing, a series made for BBC2 in collaboration with Mike Dibb and others, and intended as a riposte to Kenneth Clarke’s Civilisation.

In many ways the BBC series was directly inspired by Benjamin’s essay, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, particularly in its emphasis on photography as the upstart young rival of painting, the product of an industrial, technological and commercial age. Berger made a number of important points in the course of the series. That seeing is dependent on looking, which is itself an act of choice. That the objects of our looking are not simply things but the relationships that exist between things, and between things and ourselves. That every look establishes a particular relationship between ourselves and the world we inhabit, and that it is at the same time highly personal, reflecting the concerns of the viewer, the bearer of the look. There is an implicit affinity between Berger’s interpretation of the look and Sartre’s in Being and Nothingness, a look that is dialectical, going with the assumption that we, too, are looked at, that we, too, become objects of the gaze of others. In Franz Hals’s portrait of the Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse in Haarlem, the Regents, as Berger notes, look back at the painter, whom they see as a social inferior, even a pauper. He, on the other hand, must strive to see them as objectively as he can, to avoid the temptation of seeing them as a poor man might naturally see them, eyes fixed on his rich clients with envy, contempt or flattery.

Among Berger’s reflections, perhaps the most influential was his analysis of the nude, the naked woman as a recurrent subject for painting, and his conclusion that it reflected the imbalance of power between the male, master of the gaze, and the female, object of the gaze, an imbalance accentuated by the probability that the future owner of the painting would also be male (and clothed). He goes on to argue that, because an oil painting is typically a commodity, it transforms ‘the look of the thing it represents’ into a commodity. Hence there is an analogy between ‘possessing’ and ‘the way of seeing which is incorporated in oil paintings’. He cites Lévi-Strauss as observing that ‘it is this avid and ambitious desire to take possession of the object for the benefit of the owner or even of the spectator which seems to me to constitute one of the outstandingly original features of the art of Western civilisation.’ Berger himself suggests that the norms of oil painting – ‘its own way of seeing’ – were not established until the 16th century, remaining unchallenged until they were undermined by Impressionism and then, at the beginning of the next century, overthrown by Cubism. If this were true, however, Cubism should have changed not only the concept of painting but also the relationship of art to property and possession. It would be more accurate, perhaps, to say that Cubism changed an entrenched way of seeing and thus created a new way of looking, as a complex and multifaceted image was conceptually integrated by the viewer.

Berger’s writing about art is full of extraordinary and unexpected insights, but it has its blind spots. He sees art in conventionally optical terms – looking, seeing, representing, envisaging. But what about Helio Oiticica or Cildo Meireles in Brazil and Argentina? Mary Kelly and Hans Haacke in London and New York? The Sots Art of Komar and Melamid or the installations of Ilya Kabakov from the former Soviet Union? There is no mention of Gerhard Richter and Konrad Lueg’s Demonstration for Capitalist Realism or Josef Beuys’s Fluxus-based installations. I understand why Berger might be unhappy with, say, Warhol’s celebration of the commodity, but it seems that much of the art of the 20th century has passed him by. His enthusiasm turned towards photography, a medium which is inherently realistic, although it also reflects a technology-based way of seeing. On the other hand, one of Berger’s most exciting works is his recent collaborative book, I Send You This Cadmium Red . . . It consists of an exchange of letters between Berger and his friend John Christie, together with swatches of pure colour and fascinating discussions of true red, burnt umber, the bluest blue and the ultimate yellow.

It is also a book which reveals how subjective Berger can be in his approach to art – how he can see splotches of colour and respond that ‘from afar this is hare’s blood’, or say of a list of materials used by Beuys that

they are malleable substances, all of them, the opposite of harsh. And this is why they all seem to have something to do (even when they don’t) with a living body. And the vulnerable living body was (as I see it) Beuys’s constant subject. All his work is a searching and questioning about how the human body can find a way of being in the brutal synthetic modern world. It’s about the secret survival of the body, no?

There is a continuity here, between our ‘way of seeing’ and our ‘way of being’, specifically in relation to the body, but there is also an interest in the materials of art, rather than the appearances. There is a long meditation on Yves Klein’s self-created blue, the blue of the Madonna’s robe, the blue of lapis lazuli from the mines of Afghanistan, describing blue both as the colour of the sky – ‘space, emptiness, infinity’ – and also the colour of adornment, and a reminder of Charlie Parker, blueberries, even ‘blue’ films. Yellow, in contrast, is always the sun but also a stain, and the yellowest thing is saffron, ‘both a stain and a taste’.

I keep having to remind myself that Berger, despite his concentrated seriousness, is quite capable of breaking out of the box, seeing things in unexpected new ways, becoming excited by the unusual and the perverse and the eccentric, bringing a pungent subjectivity to the most delicate of judgments. For me he is the man who has written movingly about Seker Ahmet and the Douanier Rousseau and the Facteur Cheval, artists from outside the mainstream, who created their own strange worlds, in which the perspective was disjointed, ‘deeply and subtly strange’, or in which ‘clumsiness was the precondition of eloquence’ or which were filled with ‘strange sculptures of all kinds of animals and caricatures’. Or Grandville’s engraving of a bear dejectedly pulling a pram. Or the amateur artists of Hiroshima. Or the carvings of white wooden birds, with wings and fan tails, about six inches long, made from well-soaked pine-wood and hung in the kitchen of a peasant home, in Czechoslovakia, in the Baltic lands, or in Berger’s own Haute-Savoie. This is the Berger I admire most, a man who is at home anywhere, curious, intense, always on the side of the underdog and the eccentric, always thrilled by creativity.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.