In June 1995, the Museum of Modern Art in New York announced that it had acquired a series of 15 paintings by the German artist Gerhard Richter, collectively entitled October 18, 1977. At 11 p.m. on 17 October, the prison officer in charge of the four prisoners on the seventh floor of the high-security wing of Stammheim prison in Stuttgart had noted in his night duty report: ‘23.00 hours. Baader and Raspe given medicaments. Otherwise no incidents.’ The following morning, at 7.41 a.m. – breakfast time – guards discovered Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin dead in their cells. Jan-Carl Raspe was badly wounded. He was rushed to hospital but died soon afterwards. Irmgard Möller, who was also taken to hospital, survived. She had stabbed herself with a knife; Baader and Raspe were shot in the head and Ensslin was found hanged. There are those who believe that the prisoners were murdered, but that is not my view.

The trial of these prisoners on murder charges had begun on 21 May 1975, in a fortified courtroom built for the occasion and further protected by a barbed-wire fence, a detachment of mounted police on constant patrol and canted steel-netting installed above the roof, as a defence against a possible rocket attack. Everyone who entered the courtroom was searched, including the lawyers (though not the judges). Trouser pockets were emptied and their contents placed in plastic bags. The prisoners had been arrested in 1972. Ulrike Meinhof was found hanged from a window grating in her cell on 9 May 1976. After Meinhof’s death the defence lawyers, including one court-appointed lawyer, proposed the following motion, promptly rejected by the judges:

A person wholly deprived of freedom makes use of the most mysterious and deepest human freedom there is, the taking of her own life. That should be grounds for deferring the schedule and sending outside witnesses home, so that this state of affairs can be worked out. Something akin to reverence in criminal procedure should make it impossible for the trial to continue while the mortal remains of such a person have not yet been laid to rest.

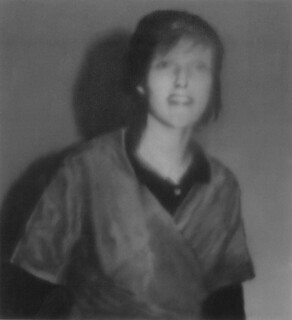

The 15 paintings in Richter’s series are based on images from his extensive collection of photo-clippings, a collection previously organised and exhibited under the title Atlas. The series begins with a painting of Meinhof from a photo taken in 1970, when she was 35, probably for publicity purposes. This is followed by two paintings of the arrest of Holger Meins, Baader and Raspe in 1972, images taken from a news video shot for German TV. Meins died in Stammheim in November 1974, after going on hunger strike. There are three pictures of Ensslin from photos taken shortly after her arrest, apparently on the way to an identification parade (one of them is reproduced on this page). The series also includes an image of Ensslin’s hanged body (shown below); an image of Baader’s cell, dominated by its crowded bookcase; an image of the record-player in which Baader is thought to have secreted the gun which killed him; two images of the dead Baader and three head and shoulders images of Meinhof on the cell floor after her body had been found. These were all official photos from the Stuttgart prosecutors’ office. The final image, taken from news footage, shows three coffins being carried through the crowd at the prisoners’ funeral.

Much of this information is given in October 18, 1997, published by the Museum of Modern Art to accompany its first exhibition of the Richter series. It seems that the Museum chose to commission and publish the book for two principal reasons. First, to underline the importance it gave to the acquisition and, second, to aid and shape public understanding of Richter’s cycle of paintings and so to validate its decision to acquire the work despite its controversial subject-matter. Guernica had been exhibited in the Museum for years, of course, but Picasso’s painting, though plainly political, is plainly anti-Fascist, too. Richter’s painting, on the other hand, is open to the charge of hagiography, of honouring the memory of terrorists, and it was now being exhibited in the city which had undergone the World Trade Center bombing, at a time when Americans were particularly concerned with the danger of terrorism, both international and domestic, in the wake of the Oklahoma City bombing.

The Museum was right, I am sure, to defend Richter against the charge of hagiography and, although the charge of exploitation might be stronger, I am not convinced by that either. On the other hand, Richter has taken great care not to express any detailed opinion of his own about the events which culminated in Stammheim in October 1977 or about the way in which the work might best be interpreted in the context of its subject-matter, preferring to leave his own intentions opaque and so, in a certain way, encouraging speculation while disarming direct criticism. I am happy to speculate. First, it is important to look at the form of Richter’s work as well as its content. For many years he has painted from photographs, as have many other artists, whether by silk-screening them directly onto canvas, like Rauschenberg or Warhol, underpainting or overpainting them, or by projecting them onto the canvas with a slide projector, or by collaging them, or simply by using them as source material, as with work by Francis Bacon or Richard Hamilton. Photography has long been used by artists as a substitute for drawing or as an iconic intermediary between reality and representation.

Richter makes use of photographs in a way which is both extremely personal, even idiosyncratic, and extremely pointed, even polemical. Since the early 1960s he has been painting photographs in such a way as to obscure the original image – an image drawn directly from the real world – and to overlay it with a painterly veil or screen which can only be described as verging on the abstract, like Bacon’s work in some respects, but much more extreme in its trajectory towards abstraction. Moreover, in his use of paint, Richter has long favoured monochrome, although there are a few exceptions. In the case of the paintings that make up October 18, 1977, his palette is confined to the grey scale and the original subjects – or rather the photographic images of the subjects – are viewed through an obscuring fog of grey, modulating at times into black. There are no clear outlines. Everything looks as if it has been smudged or shaken. As critics have pointed out, Richter creates an effect quite counter to the advice that any good photographer would naturally give: his images are blurred as if the focus was wrong, the camera had shuddered or the subject had slipped away into an evanescent haze. These effects are created deliberately, with paint.

Richter was born and brought up in Dresden. He studied painting at the Dresden Fine Art Academy but, in 1961, went to the West, where he became a student again, this time at Dusseldorf’s Academy of Fine Arts, the base of Joseph Beuys. The following year, he produced a painting in oil based on a photograph he had found in the style magazine Domus. Entitled Tisch (‘Table’), it is painted entirely on the grey scale, with no hue but with some variations in brightness. It is not an easy painting to read, even when you know its title and its origin, and seems to fall somewhere between allusion and abstraction. For Richter, photography suggested a way forward for painting which would enable it to incorporate the lessons of abstraction, minimalism and the informel, while working with photographic sources rather than directly from life. As Richard Hamilton has observed, at that time ‘somehow it didn’t seem necessary to hold onto the older tradition of contact with the world. Magazines, or any visual intermediary could as well provide a stimulus.’

At the end of the 1960s Richter began using photographs which he himself had taken and, in 1969, he began to paint landscapes, featuring waves and clouds and other phenomena which, even in nature, have no clear outlines. Then, in the 1970s, he moved on to painting abstract works, entirely within the grey scale. At first they were just called Grey but, in due course, he gave them titles such as Tourist (Grey) and Tourist (with 2 Lions) or, more minimally, Tourist (with 1 Lion). In a letter written in 1975 Richter observed that, at first, he had produced grey paintings out of misery at his own state of uncertainty, but that subsequently he was able to surmount his personal misery as he came to understand that grey was essentially impersonal, ‘the epitome of non-statement’. He became attracted, even committed, to grey because it was ‘suitable for illustrating “nothing”’; because it was ‘the welcome and only possible equivalent for indifference’; because grey, ‘just like shapelessness etc, can only notionally be real’; because each picture ‘is then a mixture of grey as fiction and grey as a visible, proportioned colour surface’. In other words, grey is simultaneously both real and unreal, committed and uncommitted. In the grey photo-based work the real is given a ‘transcendental side’, each object has its own particular mysteriousness, becoming a metaphor as it melts away into an ‘incomprehensible reality’.

The relevance of Richter’s understanding of grey to the grey overpainting which we see in the October 18, 1977 series – which was begun in March 1988 and first exhibited in February 1989 – is correspondingly both clear and unclear. These images are not abstract. They represent realities, people and objects which really existed, events which really took place. At the same time, they are given a veil of mysteriousness or even incomprehensibility – a conceptual blurring. We feel, simultaneously, both the reality of the grim events of October 1977 and their unreality, the difficulty we have in comprehending or evaluating them. Partly this is because the actual course of the events is still far from clear. We know unambiguously who or what these images of people or objects or scenes represent – we can recognise them and relate them to events which we know occurred in the real world – but at the same time they have a ‘transcendental side’, they melt away into uncertainty and unreality. In one sense, this corresponds to the historical uncertainty which surrounds the events themselves, to our lingering uncertainty as to whether these deaths were suicides or, in some sense, murders.

For a number of reasons, I am convinced the deaths were suicides, although the prison regime played its role. First, because the prisoners had already gone on hunger strike, and because, after that, the resort to hunger strike as a means of protest had become a basic option for them. One such strike had led to the death of Holger Meins. Baader had always insisted that protests should be group-based rather than individual actions, so it makes sense that the group’s concluding act should be a deliberately collective one, even though the means of death varied from prisoner to prisoner – which would in itself have been unlikely in the case of a killing by outsiders, particularly since one of the group survived. Nonetheless, no explanatory notes or statements were left behind and the three deaths remain in many ways mysterious. (The deaths of the Baader-Ensslin-Raspe generation of the Red Army Faction, far from spelling the end of the Faction’s activities, cleared the path for a ‘Second Generation’, as the group now became known, and eventually for a ‘Third Generation’, which continued to be active into the 1990s.)

Perhaps the closest we can come to understanding the group’s reasoning is by trying to think through the implications of their fascination with Moby-Dick, the story of a suicidal mission directed against a leviathan. In 1972 Meinhof was already recommending the novel to her children and Gudrun Ensslin, always practical-minded, used it to provide cover names for the Stammheim prisoners in their clandestine communications – Baader was Ahab, Meins was Starbuck, the group’s lawyer, Horst Mahler, was Bildad and Ensslin was the ship’s cook, Fleece in Melville but Smutje in their private code. In the book the whale is finally killed, but so too, of course, are all the crew, from captain to cook, with the single exception of Ishmael, to whom the closest surviving equivalent is perhaps Astrid Proll, the author and editor of Baader-Meinhof: Pictures on the Run, 67-77, a historical compilation of around a hundred images which includes most of those used by Richter, simply reproducing the photographs rather than transfiguring them into paintings.* Proll began to assemble the images in 1985, when Stefan Aust commissioned her to find photographs as illustrations for The Baader-Meinhof Group: The Inside Story of a Phenomenon, but her own volume provides much fuller visual documentation, including, for example, the extraordinary press photograph of one of Rudi Dutschke’s shoes, left in the street in front of the Students for a Democratic Society centre in Berlin, after he was shot by a right-wing extremist.

Dutschke’s shoe is right in the foreground of the photograph. Its status as the sign of an event is extremely clear, even though – or rather precisely because – it has been detached from the missing body of its owner. The October 18, 1977 cycle, in contrast, is deliberately opaque. As Gertrud Koch puts it in her essay, ‘The Open Secret’, published in Paris in 1995, ‘what characterises these paintings is their reference to the temporality of our imaginations, the haziness of our memory, its vagueness, the sinking into amnesia, the disappearance and blurring’. Koch stresses the clouding which overtakes any historical event as it loses definition in our memories. Of course, for a German like Koch, such clouded images must seem all the more ‘death-bearing’, because through their very cloudiness the viewer experiences her own ageing, the growing gap between the event and the memory of it.

In another context, the murkiness reflects our doubts about the long-term meaning of the Baader-Meinhof group’s actions, how their fateful trajectory should best be interpreted today, thirty years later. Does the passage of time make interpretation more difficult, as Richter seems to suggest and as Koch claims quite explicitly, when she talks of ‘the haziness of memory’ and of our ‘sinking into amnesia’? Without Richter, I doubt that I would now be thinking much about the Red Army Faction and the fate which befell its protagonists in Stammheim. Looking at his cycle of paintings, however, forces us to travel back in time and try to bring our thoughts about the group back into focus.

The Red Army Faction has, for another reason, been in the news recently. In January, the papers covered the arrest of the German Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer’s former friend Hans-Joachim Klein and his trial on charges related to the terrorist attack on an Opec meeting in Vienna in 1975, in which three people were killed. According to the New York Times, the sudden resurrection of Fischer’s past was largely due to the ‘unrelenting vendetta’ against him ‘carried out by the daughter of Ulrike Meinhof, the Red Army Faction terrorist who committed suicide – or was killed – in prison in 1976’ and ‘the discovery by Ms Meinhof’s daughter, a 38-year-old journalist, of the photographs of Mr Fischer hitting Mr Marx’ – a policeman – ‘from behind and then kicking him on the ground’. There was also the fury of a retired policeman, Horst Breunig, in regard to Fischer’s actions in another demonstration, provoked by the death of Ulrike Meinhof in Stammheim prison. And so the fading images begin to come back more clearly into focus, as old scores are settled.

I was particularly intrigued by the role played in the Joschka Fischer story by Klein, and by Klein’s connection with Sartre. In February 1973, Sartre told Der Spiegel that he was ‘very much interested in the Baader-Meinhof group. I believe it is a real revolutionary group, but I have the feeling it has started a little too soon.’ The following year, Les Temps modernes published an article on the ‘torture by sensory deprivation’ inflicted on Baader-Meinhof prisoners, and in October 1974, Ulrike Meinhof wrote a letter to Sartre inviting him to come and interview Baader in prison, warning him that the police ‘intend to murder Andreas’. She explained: ‘It’s not a necessary condition of the interview for you to agree with us on all points; what we’re asking is that you’ll give us the protection of your name and your gifts as a Marxist, philosopher, journalist and moralist in the interview.’ In November, Holger Meins died in Stammheim. A few weeks later, Sartre finally agreed to visit Baader in order to show solidarity with him as a prisoner, though he disapproved of the group’s use of violence. It was Hans-Joachim Klein who drove the car which took Sartre to Stammheim.

Nothing ever came of Sartre’s intervention. There was never any chance that the prisoners’ conditions would be changed, as Sartre himself realised. In any case, the regime imposed in Stammheim could be surprisingly lax. As Aust notes, the record-player which features in one of Richter’s photo-paintings was used to play records from a collection of seventy-odd LPs which Baader had accumulated in his cell, together with speakers, an amplifier, a typewriter, a mouth-organ, two fur coats, two pairs of sunglasses and, of course, guns. The guns, it is reasonable to assume, were smuggled in by the defence lawyers. Baader, according to Aust, had for some time had a 7.65 FEG pistol hidden in his cell wall, which he transferred to a hiding place in his record-player sometime after 11 p.m. on the 17th, when the prison officers made their last visit.

Raspe also had a gun, hidden behind a skirting-board. During the night, the prisoners were able to communicate by means of the electricity circuits which connected their cells, having adapted elements of their stereo equipment to create an intercom system. They had previously succeeded in setting up an internal radio system, known as ‘Stammheim III’, which had been detected and dismantled, yet somehow the intercom escaped detection until after the suicides had taken place, when it was uncovered by a visiting Federal Mails engineer. The prison electrician acknowledged that he had been quite unaware that the power supply could be used to convey messages. Aust concludes that, after a suicide pact had been agreed over the intercom, the two guns were removed from their hiding places by Baader and Raspe, while Ensslin cut a stretch of loudspeaker cable with her scissors and tied it to the window grating. Disconnected from any kind of normal contact with the outside world, a condition exaggerated still further by a regime of isolation, strict surveillance and sensory deprivation, it is hardly surprising that the group members sought a way to end everything. Suicide was consistent both with their sense of despair and their sense of purpose. It was also a goal that they could achieve.

The prisoners had threatened to kill themselves on a number of occasions. On 8 October, for example, Baader had told Alfred Klaus, head of the Special Commission on Terrorism, that they would soon reach an ‘irreversible decision’ if prison conditions were not improved. The following day Ensslin also asked to see Klaus. She told him that, unless improvements were made, the group would ‘take the decision out’ of Chancellor Schmidt’s ‘hands by deciding for ourselves, in the way still open to us’. Klaus interpreted this statement, too, as a suicide threat, recalling that in a letter intercepted three years before, Ensslin had suggested that the prisoners should consider committing suicide as a group, one at a time over a period of weeks. On 27 September, Raspe had also explained that a failure to change their situation would inevitably lead to ‘dead prisoners’, which would be a ‘political catastrophe’, presumably for the Government. On 9 October, Raspe was asked directly by Klaus whether he was planning suicide and replied that it was possible. ‘A living dog is better than a dead lion,’ Klaus observed. ‘That’s from Ecclesiastes.’

The Stammheim suicides were the most effective action taken by the Baader-Meinhof group. In fact, it is difficult to pick out anything else very positive that the group achieved. They proved adept at robbing banks, stealing cars (especially BMWs but once an Alfa Romeo), shooting cops, setting fire to a department store, exploding bombs, corrupting lawyers, baiting judges, hiding from the police, throwing Molotov cocktails, negotiating ransoms, killing soldiers, considering sending their children to Palestinian orphanages, quarrelling with each other, taking uppers and downers, imposing on other people’s hospitality, organising hijackings, taking hostages, forging passports and putting on disguises, but none of these activities had the same impact as their suicides. A sad record, when one considers the beliefs and hopes – for socialism, a non-consumerist society, nuclear disarmament and an end to psychiatry – that first drove them into their campaign of violence. Armoured against doubt, driven by fear of what might happen if their certainties were abandoned, desperately struggling to maintain their sense of self, afraid of each other’s contempt, they staggered from idealism to self-destruction.

There was an enormous cultural response to the suicides. The following year, the film Germany in Autumn was made, with contributions from, among others, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Alexander Kluge, Edgar Reitz and Volker Schlondorff, working together with Heinrich Böll. The Schlondorff-Böll episode showed a panel of TV programmers rejecting a production of Sophocles’ Antigone because it showed Antigone’s suicide after Creon refused to allow her to bury her brother, a rebel against the state. The film begins with the public funeral and official mourning of Hanns-Martin Schleyer, president of both the German Employers’ Association and the Federation of German Industry, who was held hostage and then executed by the Red Army Faction in response to the deaths of the prisoners in Stammheim. It ends with the public funeral and unofficial mourning of the prisoners. It is a Trauerarbeit, both a demonstration and an enactment of grief. It reminds us that the suicides, at least, attracted sympathy to the Red Army Faction and conveys a sense that something had been lost, that something was amiss.

Fassbinder’s section of the film shows both his panic when a homeless stranger comes to his apartment and, even more intensely, his fear that the police are at the door. In an interview, he described the suicides as the result of a ‘witch-hunt’, the aim of which was ‘to destroy individual utopias’, a witch-hunt he felt to be personally threatening. In Yvonne Rainer’s film Journeys from Berlin/ 1971, made in 1980, two off-screen characters discuss the Stammheim deaths. One compares the Red Army Faction to the ‘Russian Amazons’ who ‘went to the people’. ‘My point,’ she says, ‘is that the Baader-Meinhof people preferred robbing banks and kidnapping to going to work in factories.’ She goes on to accept that Meinhof’s writing ‘sounds like hysterical rhetoric’ but says that ‘she must have suffered horribly in prison,’ contrasting the isolated, sound-proofed cell in Stammheim with Rosa Luxemburg’s access, while imprisoned, to a garden where she could grow flowers and listen to the birds. In Fassbinder’s 1979 film, The Third Generation, the terrorists are portrayed merely as providing a pretext for the generous funding of the security and surveillance industries. As Anton Kaes notes in From ‘Hitler’ to ‘Heimat’, ‘Utopia no longer appears as even a vague possibility.’

For Richter, I think, the uncertainty has never quite gone away. ‘I’m not sure whether the pictures “ask” anything,’ he wrote in his notebook: ‘they provoke contradiction through their hopelessness and desolation, their lack of partisanship.’ His original motivation, he said, was ‘“purely human” (dismay, pity, grief)’, without any ideological content – and yet ‘the pictures are also a leave-taking in several respects. Factually: these specific persons are dead; as a general statement, death is leave-taking. And then ideologically: a leave-taking from a specific doctrine of salvation and, beyond that, from the illusion that unacceptable circumstances of life can be changed by this conventional expedient of violent struggle.’ What, if anything, is to replace it? To my mind, Richter feels that it can only be grief. Ideas, he writes, have ‘a terrifying power’ which was demonstrated in Stammheim, but which should be regarded not in terms of the horror we feel when we see the photographs, but in terms of the grief (or ‘something more like grief’) which we feel when we see the paintings, a grief we feel in response to the loss both of the individuals and of their illusions.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.