In the 1960s we used to sing a music-hall song in the pub whose rousing refrain began, ‘Two lovely black eyes – Oh, what a surprise!’ and went on: ‘Only for tellin’ a man he was wrong – two lovely black eyes!’ It took me a while to realise that the singer was a woman who’d been beaten up by her bloke because the song made me laugh so much, especially when we all whooped in chorus on the ‘Oh’, raising our eyebrows melodramatically. Stories of men given to hitting their women weren’t unheard of in my family, but I associated them with my grandparents’ generation, like chenille tablecloths or mangles or the music hall itself. ‘In the old days’ there were men who liked their drink a bit too much and ‘took it out’ on the wife. Wife-beating, in theory at least, belonged to the dark ages. Hitting children, however, was commonplace; a mother slapping a toddler round the legs was a familiar sight in public, though hitting one across the face wasn’t. Corporal punishment at school was routine (in Penhale Road Infants’ we were rapped across the knuckles with a ruler) and in the course of his growing up my brother got thrashed with a belt, caned and slippered. There were limits, even so. When a sports-master at the grammar hit him so hard with a hockey stick that his back broke out in raw, crescent-shaped welts, my mother went in a fury to the headmaster. She got an apology but the teacher kept his job.

I grew up with a colourful language of aggression, much of it centuries old, like the threats of a ‘whopping’ or a ‘walloping’, a ‘good hiding’ or a ‘tanning’ (or, less frequently, ‘a leathering’, which also harked back to the treatment of animal skins). Mostly it suspended violence over our heads like the sword of Damocles. Everybody menaced children all the time: parents, neighbours, shopkeepers, bus-conductors, you name it. ‘I’ll wring your neck!’, ‘I’ll knock you to kingdom come!’ (or, one of my favourite variations, ‘into next week!’) and ‘I’ll murder you!’ were heard so frequently as to suggest a society of psychopaths. Taken more seriously were the quieter forms of intimidation, as when your mother asked, ‘would you like to see the back of my hand?’ or offered to ‘give you something to cry about’ (or, more ominously, ‘something to remember’). ‘Wait till your father gets home’ was the ultimate deterrent. An afternoon spent in anticipation could feel like a lifetime.

I was rarely smacked and, of course, I knew the difference between a threat and a blow. A smack, when it came, was meant to relieve tension and to draw a line. But anger does not always go through all its stages like a kettle coming slowly to the boil. In my childhood a foul temper was treated with respect, as if it were a force of nature, like a hurricane or volcano, and more fool you if you put yourself in its path (‘you know what his temper’s like’). Adults were always seeing red or blowing their tops; they lashed out or got ‘carried away’. Men who were ‘too fond of their hands’ – this was usually meant as an apology after the fact – ‘didn’t know their own strength’. It hurt to be smacked (and it was never, not once, fair), but I dreaded people getting angry: the shouting, the red faces, the raised fists, the fact that anything might happen in the heat of the moment. In the bullying culture typical of many English childhoods, you are meant to stand up for yourself and to fight back. Being punished and being ‘brave’ also entitles you to a certain amount of esteem. Being afraid, on the other hand, has nothing going for it.

I begin in this way because Virginia Woolf calls Three Guineas, her anti-war book, an ‘enquiry into the nature of fear’. Three Guineas finds a kinship among fear’s victims, a move which many readers thought wrong-headed or downright foolish when the book was published in 1938, and which is still hard to take. Woolf argues that until recently women of her class – ‘the daughters of educated men’ – had been utterly dependent: they had no claim to nationality, no right of citizenship; they could not own property; they were not able to travel or mix without a chaperone; they were excluded from education and they could not earn their own living; nor could they divorce their husband or limit the number of children they had. Theirs may have been a gilded cage, but they were nevertheless imprisoned and silenced by fear – ‘the fear that forbids freedom in the private house’. They were afraid of the male aggression that surfaced in the angry opposition with which the majority of men met every stage of the struggle for equality. Woolf suggests that this fear, though it might seem ‘small and insignificant’, is connected to the fear at large in Hitler and Mussolini’s Europe. She identifies the experience of those being persecuted under Fascism with that of her mother’s generation: ‘You are feeling in your own persons what your mothers felt when they were shut out, when they were shut up, because they were women. Now you are being shut out, you are being shut up, because you are Jews, because you are democrats, because of race, because of religion.’ For Woolf fear is the controlling force, and is as destructive and as violating, to those who live in its grip, as physical aggression.

Three Guineas is Woolf’s angriest book and her most overtly pacifist; its prompt and provocation was the question around which it revolves: what could women like herself do to help prevent war? Pacifists and warriors have long been locked in each other’s arms: the study of anger has been the pacifist’s task. Three Guineas belongs to that flood of pacifist writing in the 1930s which concerned itself with ‘war psychology’ and found the roots of warmongering in education (this was Bertrand Russell’s position in his 1936 pamphlet, Which Way to Peace?) or in the greed and competition integral to capitalism (The Roots of War, published by the Hogarth Press in the same year, took this line). As Hermione Lee pointed out in her biography of Woolf, Three Guineas reiterates much of the debate over peace and war which split the Left in the mid-1930s, but whose complexity, it might be added, has disappeared beneath the weight of that derogatory term, ‘appeasement’. Nor was Woolf’s combination of feminist arguments and a pacifist stance new. Feminists during and after the First World War (many of them in Woolf’s circle) had played a central role nationally and internationally in the establishment of pacifist organisations, arguing against the seductive emotional rhetoric of patriotism, and claiming that women had different insights and experience which made them especially effective in ‘peace-diplomacy’. Three Guineas made a disturbing leap into the dark, however. As well as being Woolf’s denunciation of Fascism it attempts to bring Fascism’s emotional and psychic violence home to the British. The Fascist is one of us – a view which was for many readers simply too much.

Three Guineas looks to the psychological, to what goes on inside – ‘in your own persons’ – for an understanding of the way inner economies, disciplines and controls might generate as well as reinforce the economic and political structures without. It was Woolf’s response to the worsening situation in Europe, her search for meaning beyond the horror and misery she felt at the ‘idiotic, meaningless, brutal, bloody, pandemonium’ of Hitler’s rise to power and the increasing likelihood of another war. Woolf’s republic of fear, where being dictated to feels the same whether it is by the state, by institutions or by individuals, is a boundless space, but it is also a deeply familiar one. Like Wilhelm Reich in The Mass Psychology of Fascism, written in the early 1930s, Woolf turns to the emotional and psychic structures of the patriarchal household and its sexual relations, maintaining that ‘the public and private worlds are inseparably connected; that the tyrannies and servilities of the one are the tyrannies and servilities of the other.’ The Victorian family, devoted to the father-figure, demanding the subordination of women and based on the jealous possessiveness of capitalism, shored up the pugnacity, greed and hypocrisy of public life. Both private and public life fostered the slavish worship of hierarchy and social status. Without the proprietorial mentality of the 19th-century paterfamilias, that confidence in ‘the traditions of mastery’ at home, the British Empire abroad would have been unimaginable, and the debacle of 1914 equally so. But for Woolf, not only is militarism only a stone’s throw away from civilian masculinity, but all forms of masculine authority shade into authoritarianism. The political dictator differs only in degree from the suburban tyrant treating his home as his castle or ruling his family with a rod of iron. The university lecturer imposing himself on docile minds and the civil servant lording it in the corridors of power are both little Hitlers, swept together in Woolf’s rhetoric: ‘The whole iniquity of dictatorship,’ she writes, ‘whether in Oxford or Cambridge, in Whitehall or Downing Street, against Jews or against women, in England or in Germany, in Italy or in Spain is now apparent.’ In Three Guineas the 1850s slide imperceptibly into the 1930s. Woolf’s phrase for the ladies of the mid-19th century, ‘the daughters of educated men’, serves equally to describe those born twenty-five, even fifty years later.

Woolf offers a chapter in the psychosexual history of the English middle classes. Three Guineas wants to understand the warmonger but it is not a discussion of aggression (or of ‘aggressivity’) or of war in general; it wants to see the ‘male habit’ of fighting as a matter of ‘law and practice’ but it has nothing to say about female aggression. It maintains that only dictators make fighting the essence of virility (and concomitantly deem passivity cowardly and womanish), yet the history of feeling, which Woolf evokes, constantly sexualises aggression as a masculine trait (‘your anger, our fear’, as Three Guineas puts it). Naomi Black, the book’s most recent editor, observes that ‘violence against women goes virtually unmentioned’ in Woolf’s account. But behind the fear that men’s upbringing might breed violence lies a deeper fear, approached tentatively but knowingly in the text through the use of ellipsis: the fear that male aggression always has an erotic component, that fathering might be founded on conquest, that the laying down of the law is always violent and is always what makes a man. In Woolf’s account of heterosexuality, desire appears both masculine and predatory: it is ‘dominance craving for submission’, a mere will to power (this is the nightmare which haunts her last work, Between the Acts). In asking what women might do to help prevent war, Three Guineas wonders ‘what possible satisfaction can dominance give to the dominator?’ But it cannot tolerate identification with the aggressor for long.

Faced with the prospect of war, passivity is for Woolf the less tainted position. How might it be redeemed from the history of victimhood? Three Guineas follows much pacifist writing in proposing an esteem based on a different kind of inner discipline, a confrontation of the conflicting desires in the self, and a willing dispossession which comes close to Gandhi’s ideas of passive or non-violent resistance. Those who have been the objects of exclusion and derision are already freer, Woolf suggests, from the ‘unreal loyalties’ that prompt belligerence: ‘nationality, religious pride, college pride, school pride, family pride, sex pride’. Given the moral bankruptcy of capitalism and its ‘adulterated culture’ in which everything is mixed with the ‘money motive’, it is preferable to live modestly. To compete is to imitate: women should cultivate an attitude of ‘indifference’, ideally refusing to display any tokens of prestige or rank, flinging back any offer of public honours (Woolf turned down an invitation to give the Clark Lectures at Cambridge in 1932, refused the Companion of Honour in 1935 and honorary degrees from Manchester and Liverpool); they should abstain from any rituals which promote the ‘desire to impose “our” civilisation or “our” dominion upon other people’. ‘To be passive is to be active; those also serve who remain outside.’ The most exhilarating impulses in Three Guineas incite an imaginary violence – ‘Set fire to the old hypocrisies’ – such as the demand for ‘Rags. Petrol. Matches’ to burn down any woman’s college if its values are no better than men’s. (‘Let it blaze! Let it blaze! For we have done with this education!’) Woolf knows that women must ‘face realities’ – take jobs, pass exams, earn salaries – but she is far more excited by renunciation and by the struggles of Florence Nightingale or Sophia Jex-Blake than by the achievements of her own generation. With its fear that ‘the victims of the patriarchal system’ might become the new ‘champions of the capitalist system’, Three Guineas tries to envisage a psychic and emotional space in which those who have been infantilised, those who see themselves as weak and helpless, might move beyond a sense of inferiority without assuming mastery in return (Three Guineas deserves a place alongside Frantz Fanon’s analysis of the dependency culture of the colonised).

Three Guineas is Woolf’s most utopian book; it is also her grimmest, most anti-social. Despite its brief millenarian glimpses of future peace, her pacifism refuses any faith in the brotherhood of man (it differs markedly here from Forster’s ‘What I Believe’, published in the same year), since personal relations offer no sanctuary from power. Group gatherings or associations threaten to submerge individuals, she argues. They encourage ‘the herd mentality’, as 1930s psychology dubbed it, and that transcendentalism with which Fascism was mystifying ‘the masses’. As the life around her becomes more intensely politicised, Woolf dreams of a Society of Outsiders, working without ‘leagues or conferences or campaigns’, without procedures, and above all, without leaders. Her Society of Outsiders is to remain disembodied. There are to be no meetings to further co-operative projects, nothing mutual except at arm’s length. Only a few lonely individuals will manage this psychic economy, holding onto just enough to keep them going. Behind Three Guineas lies the terror of the concentration camp and the penal colony; Woolf’s political heroine is Antigone, whose civil disobedience led to her immolation, walled up in her tomb. For the less brave there may only be room to retreat: to live, if necessary, without hope; to work, if need be, without love.

Three Guineas was fuelled by rage. It began life in 1931 as a sequel to A Room of One’s Own. Woolf started to collect material to illustrate her views on women’s exclusion from the professions and on patriarchal bullying, pasting clippings into scrapbooks and transcribing passages from her reading (this edition offers a full account of Woolf’s research, much of which went into more than a hundred endnotes to the final text). By 1932 she’d already got ‘enough powder to blow up St Paul’s’ but went on stoking the fires, adding to her ‘cauldron’ of ideas, as she worked on other projects. It drew heat from her ‘essay-novel’, ‘The Pargiters’, borrowing from its polemical ‘interchapters’ (Woolf eventually dropped them and the fictional remainder finally became The Years). Just thinking about the work filled her with a terrifying excitement – ‘like being harnessed to a shark’. Everything was grist to her mill: the petitions for her signature she received daily in the post, political conferences, articles in the press, pamphlets and manifestos, exchanges and arguments with friends and family (especially with Julian Bell, her nephew, who was determined to join the Republicans in Spain; his death there in 1937 made the book seem more necessary). The drafting, when it began in 1936, raced and galloped violently. It was an explosive experience: ‘It has pressed & spurted out of me,’ she wrote, ‘like a physical volcano.’

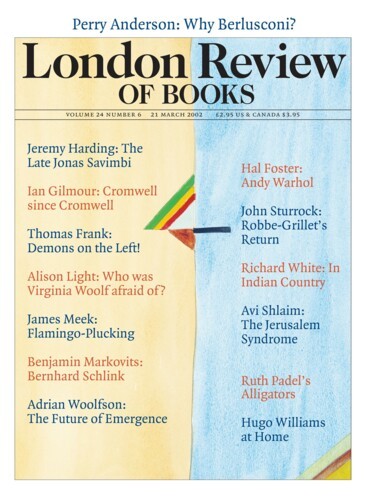

Naomi Black calls the gestation of Three Guineas a ‘period of postponement’ but the years of allowing her ‘sizzling’ brain to cool, as Woolf put it, enabled the transmutation of anger into what she wanted for the book: ‘beautiful clear reasonable ironical prose’. Three Guineas is deliberately diffuse and yet elaborately structured. It is framed by a series of undated, unlocated first-person replies from an anonymous, rather arch lady to those asking for funds and support. Like a Chinese box, each letter contains within itself versions of other letters the writer has received and drafts of the replies which she may send. ‘The fiction of the letters’, in Naomi Black’s phrase, acts as camouflage. Woolf’s indictments, her ventilation of the airless world of masculine self-importance, her pillorying of the smug cliquishness of interwar Britain, and her history of professional misogyny, are handled lightly and satirically; the endnotes frequently borrow novelistic techniques and, as Keynes rightly complained, ‘made a mockery of our history’: Woolf ridicules the wearing of ‘pieces of metal, or ribbon, coloured hoods or gowns’ to express ‘worth of any kind’. Three Guineas includes photographs of a general, a herald, a university procession, a judge and an archbishop looking suitably absurd in full fig (they were mysteriously cut in the 1968 and 1977 reprints of the Uniform Edition). But every incendiary impulse, however much relished, ultimately hangs fire. Woolf worried while writing that she was being too conciliatory: ‘I so slaver & silver my tongue that its sharpness takes some time to be felt.’ Leisureliness and flippancy were antidotes to the ‘braying’ loudspeaker tone, which she so disliked, its association with the ego-politics of Fascism, and her fear that all political argument was likely to harden into orthodoxy and the taking of sides. Three Guineas refuses to dictate. Its irony protects the reader from the violence of its polemic.

Black’s introduction makes plentiful use of quotations from Woolf’s diaries but consistently omits or truncates those comments which suggest her ambivalence about the work or about politics in general (she is troubled, for example, by ‘the vulgarity of the notes’, by ‘a certain insistence’). Black cites the diary entry dealing with Woolf’s attendance at the crucial Labour Party Conference of 1935 where George Lansbury resigned as leader after a dramatic attack on his pacifism by Ernest Bevin – this was a turning point in the evolution of Three Guineas, the moment when the connection between feminism and Anti-Fascism seemed to fall into place. She passes over Woolf’s shrugging dismissal of the political situation as a whole, written as if her exclusion from politics in the past left her utterly blameless in the present: ‘Happily, uneducated & voteless, I am not responsible for the state of society.’ Woolf’s desire to be ‘immune’, and her belief that her art depended on an energy which came from being detached and uncommitted, often looks like a refusal of those ideals of agency on which so much feminism has prided itself. Black reassures her reader that Woolf was not as ‘frivolous’ about feminism in person as her writing sometimes is: Three Guineas is ‘explicitly feminist’, she insists, ‘in spite of some coy denials’, thus glossing that inconvenient passage which hankers to consign the word ‘feminist’ to the flames – ‘an old word, a vicious and corrupt word that has done much harm in its day and is now obsolete’.

This edition, however, gives us an American Woolf, long known to be a different species from the native variety. Despite the English canonical ring of Blackwell and its imprint ‘The Shakespeare Head Press’, this series of Woolf texts relies on a team of Canadian and American scholars (with the exception of Andrew McNeillie), is aimed mostly at American students (Black annotates ‘coalscuttles’, ‘margarine’ and ‘ironmongers’, for example), and sometimes takes the marked-up American proofs as copy-texts, thereby publishing editions which Woolf’s British public never read. North American critics did much in the 1970s and 1980s to combat the view of Woolf as an effete stylist, the Invalid Lady of Bloomsbury, and their painstaking textual scholarship frequently went hand in hand with a recovery of her feminism. Black thinks it ‘odd’ that the British, including the editors of the Penguin and Oxford World’s Classics editions of Three Guineas, take issue with Woolf and highlight her ambivalences. But it’s equally odd that a scholarly teaching edition should see its role as celebratory, preaching only to the converted.

It is astonishing that Woolf continued to stake so much on feeling disenfranchised – how much it still rankled, that old grievance of being ‘uneducated’. So much, it seems, that she saw no incongruity in telling the men and women of the Brighton Workers’ Educational Association whom she lectured in January 1940 that she was one of them: she didn’t look at things, she said, from ‘the leaning tower’, those heights from which public school and university men surveyed the world. Not everybody believed her. Her claim that the ‘daughters of educated men’ were ‘the weakest class’ (since they could not even withdraw their labour) could seem deluded or at least myopic. Queenie Leavis’s infuriated review for Scrutiny, ‘Caterpillars of the Commonwealth, Unite!’, was particularly scathing, not least about Woolf’s inability to register any university other than Oxford or Cambridge, as though the London colleges and the redbrick universities, which had long awarded degrees to women, did not exist. For Woolf, ‘the daughters of educated men’ were not bourgeois because they lacked capital and owned little. Three Guineas does not recognise how much women of her sort had themselves generated and sustained the emotional and psychological territory of class, its cultural capital, investing in ideas of respectability and sensibility, and in their sense of being different from, and superior to, working women. Woolf did not include the power wielded by mistresses over servants in the tyrannies and servilities of the private sphere; tinpot dictators could only be male.

Naomi Black wants to believe that Three Guineas ‘consoled’ Woolf as war approached, even though Woolf was sometimes dubious, writing to one fan: ‘Whether it made any impression I don’t know. I doubt if ideas ever do.’ (Black calls her ‘disingenuous’ when she writes that ‘the book is a mere outline.’) Woolf’s diary suggests she was indeed pleased to have had her say but partly because she now felt entitled to return to ‘the real world’, the world of fiction which, like Sleeping Beauty, had been ‘barred with brambles’. Woolf’s isolation as war approached, the product partly of circumstance, partly of choice, may well have been freeing, but it may also have been a mistake. Who knows? Perhaps it was both. All we can say is that her refusal to repudiate passivity in her own creative life seems to become more self-conscious in the late 1930s. After thirty odd years as a writer, the desire to ‘own no authority’, as she put it, that negative capability which for her, as for other Modernists, came so close to the depressive position, felt like a precondition for her writing.

Why accentuate the positive? Perhaps it’s easier to legitimise an aggressive reaction to fear than the feelings of helplessness and self-hatred Woolf so often endured. But without accepting their paralysing force, it’s hard to appreciate the scale of what she achieved. And hard also to understand why she was a writer, that most passive of activities. In April 1939 Woolf began drafting her memoirs and recalled how the long indistinguishable ‘cottonwool’ days of childhood would unexpectedly be broken into when ‘something happened so violently that I have remembered it all my life.’ She gave an instance of one such ‘sudden violent shock’:

I was fighting with Thoby on the lawn. We were pommelling each other with our fists. Just as I raised my fist to hit him, I felt: why hurt another person? I dropped my hand instantly, and stood there, and let him beat me. I remember the feeling. It was a feeling of hopeless sadness. It was as if I became aware of something terrible; and of my own powerlessness. I slunk off alone, feeling horribly depressed.

Against this memory of despair, Woolf immediately set another exceptional moment, a memory of satisfaction:

I was looking at the flowerbed by the front door; ‘That is the whole,’ I said. I was looking at a plant with a spread of leaves; and it seemed suddenly plain that the flower itself was a part of the earth; that a ring enclosed what was the flower; and that was the real flower; part earth; part flower. It was a thought I put away as being likely to be very useful to me later.

Woolf hazarded that in her case the ‘peculiar horror’ of passively registering those blows was always followed by the desire to explain, the delight in consciousness and reason, in putting ‘the severed parts together’ and putting the shock into words. This ‘wholeness’ removed the blow’s power to hurt: ‘I go on to suppose that the shock-receiving capacity is what makes me a writer.’ It’s as if by the time she reached her late fifties she came to believe that not defending herself had allowed her to become an artist.

For all its fighting talk, Three Guineas is not a manifesto. It pulls its punches. It does not simply unleash Virginia Woolf’s fury at the blows which the daughters of educated men felt they had suffered; such an expenditure of emotion (like the three guineas finally donated to help prevent war) would not, in the end, go very far. But neither does it censor. In a series of feints and passes, Woolf’s writing resists and deflects the aggressive reaction, defuses the volatile emotion, making something else of it. For Woolf, as for Freud, sublimation, not retaliation, is the art of civilisation. Writing, in other words, is at best a way of becoming more mindful of one’s anger.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.