Charles Booth’s survey of London poverty was an epic Victorian undertaking. Beginning in the late 1880s with East London, Booth and his army of investigators launched a systematic study which went on to cover nearly all of the metropolis, then the largest in the world with around four million inhabitants. The accounts of their walks around London filled 450 notebooks. They visited homes and workplaces, department stores and sweatshops, street markets, pubs, music halls, gambling dens and clubs, workhouses, and every kind of church or mission. They gathered information on housing conditions, personal circumstances, rent, family budgeting, occupations and earnings, and acquired a mass of supplementary material, from letters, wage books and parish magazines to sketches of technical equipment in factories. The work was finally issued in 1902 and 1903 as the 17 volumes of Life and Labour of the People in London, marshalled under three headings: ‘Poverty’, ‘Industry’ and ‘Religious Influences’. Contemporary estimates hazarded that about a quarter of London’s inhabitants lived in want, a shocking figure that some thought exaggerated. Booth put it at well over a third.

The sheer scale of his enterprise is hard to take in. So is its novelty. Londoners, especially the poorest, were no strangers to scrutiny from charitable and religious reformers or campaigning journalists. But Booth was the first to organise a research team and to look at the whole city from a number of different perspectives, to seek out facts and use the new methods of statistics to assess them. Booth’s first measure of poverty was overcrowding. The population of London was mushrooming. The agricultural depression of the 1870s had driven rural migrants into the capital; they were later joined by Eastern European Jews fleeing persecution. At the same time, the housing stock available to the poor was deteriorating and increasingly liable to demolition as London modernised. Railways and new main roads cut swathes through the capital, and stations, warehouses, offices and public buildings displaced the inhabitants of packed residential areas. They crammed into dilapidated 18th-century housing, or into the courts and tenements jerry-built by speculative contractors on patches of land between existing blocks. Families of ten or eleven bedded down in cellars; they rented a room by the week or the night in lodging or ‘doss’ houses. Others took their chances on the streets.

Booth maintained that he was trying ‘to learn how the poor live’ rather than providing evidence for a doctrine or argument, but the descriptive notebooks on which the survey was based go far beyond fact-finding. He and his foot-soldiers asked standardised questions, but noted everything they deemed relevant. Diet and clothing, potato peelings in the streets, unmade beds glimpsed through uncurtained windows, men lounging on street corners, Saturday-night fights, the number of barefoot children, how many young women drank in the local (the women in Southwark, we learn, ‘live on fried fish and four ale’, a mild beer sold at fourpence a quart). They populated their notebooks with vignettes of dock labourers, organ grinders, costers and hawkers, ‘frowsy’ women and hard-pressed mothers, and a gallery of individuals working and living in near destitution. In Shoreditch, a Mr Harris, with his wife and children, was being ‘eaten alive by bugs’; in another ‘vile room’ in the same tenement, his elderly neighbour Mr Jones painted ‘Christmas sheets’ (presumably wrapping paper) from 9 a.m. every morning, managing forty dozen in two days. The investigators added their own animadversions and even novelistic touches. The Reverend the Honourable R. Henley, vicar of St Mary’s, Putney, was ‘an old man – well over sixty – moustache and beard slightly stained from pipe smoking’. Seeing grubby boys playing cricket in the streets of Deptford using their caps and coats as wickets, one note-taker has written an adventure story: ‘Copper!’, one lad calls out when he spies a policeman. But ‘he hasn’t got a badge on!’ another says – so they all pause ‘to reconsider the enemy’.

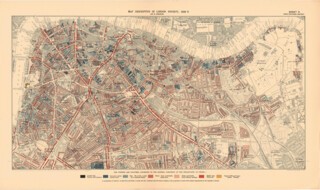

Thousands of details like these were collated and digested. Lists of figures were tabulated and percentages calculated – for population, gender, births inside or outside London – before being correlated with census data and turned into graphs and pie charts. Relying on the notebooks, Booth and his team then innovated further. The initial pilot study of the East End included ‘A Descriptive Map of London Poverty in 1889’, hand-coloured and printed by the Ordnance Survey. On it, six colours were used to signify levels of poverty in different areas.

Streets coloured black or blue marked the haunts of the ‘very poor’: Class A, deemed ‘vicious or semi-criminal’ in Booth’s terminology, and Class B (‘casual’ workers and those living in chronic want). Pale blue signified ‘the poor’: classes C (those in irregular work, struggling to make ends meet) and D (those in full-time work but on very low wages). Above Booth’s poverty line were classes E and F, who earned regular decent or good wages, and G and H – the middle classes and the well-to-do (and the rich). Relative comfort was signalled by pink; while the most affluent streets in the leafy suburbs, as well as the wide crescents and avenues in town, were coloured red or gold. Since many streets had a mix of classes, there was much crosshatching and playing with colour. Some streets were black at one end and pink at the other; blue and pink – ‘poverty and comfort mixed’ – were fused to produce a purply brown; a blue street outlined in black signalled that its very poor inhabitants, though generally law-abiding, also included those classed as ‘semi-criminal’ or ‘degraded’.

Booth’s survey was a lengthy process of collaboration and revision. Over the years the maps were updated by Booth’s assistants as they extended their coverage of the city, walking the streets and noting changes to the districts and their demographics. Inner London was getting poorer; those who could afford it moved to the new suburbs. Booth published his reports piecemeal – the second volume of the series, for instance, which came out in 1891, covered an area from Kensington in the west to Poplar in the east, and from Kentish Town in the north to Stockwell in the south. When they were published at the beginning of the new century, the finished 17 volumes of Life and Labour, written up and organised by Booth, came with 12 maps. These maps are the ‘hero’, as Mary Morgan puts it, of a new, beautifully designed gazetteer of Booth’s work. They represented in their day ‘an entirely original attempt at a visualisation of social class’.

At a glance, the blackest streets are, unsurprisingly, found in the most insalubrious places, huddled around London’s few industrial areas: the gasworks and docks, wastelands and dumps, riverside and railways. But the maps also show how much of London poverty was cheek by jowl with riches. The one-room shacks of Notting Dale, for instance, where residents took in washing and fed pigs on refuse from the West End, boiling down their fat for industrial uses, were a stone’s throw from the wealthiest parts of Kensington. Unlike columns of statistics or wordy analysis, the information on the maps could be quickly absorbed. But the colour-coding, whose logic must have seemed unexceptional at the time, was far from innocent. At one extreme the glamour and heraldic grandeur of gold for, say, Grosvenor Square or Hyde Park; at the other, black for Whitechapel or Spitalfields, conjuring a ‘dark continent’ whose ignorant, savage tribes, like those elsewhere in the British Empire, needed the clarifying light of Christian missionaries or exposure to scientific reason.

The maps were imaginative artefacts as much as scientific documents. In the new folio they have been ‘re-curated’, as the cover blurb puts it, with just a hint of the coffee-table book. The maps are already very popular with family historians, available in cheap paperback versions, and often made use of in television programmes, most recently in the BBC’s genealogical Who Do You Think You Are? and the Open University’s The Secret History of Our Streets. By themselves – without information, say, from the decennial census on the families that lived in each street – they would be inert. This volume brings them to life with a marvellous compendium of materials, including a staggering number of illustrations, photographs and ‘infographics’, six essays for the general reader – on housing, immigration, religion, trade, morality and leisure – plus facsimile pages and excerpts from the notebooks kept by Booth’s collaborators. A dozen ‘In Focus’ pages illuminate some of London’s districts, with thumbnail photos and soundbites from the survey conjuring daily life, local personalities, sights and sounds. Where the maps freeze-frame the terrain, the notebooks and photographs convey the traffic of goods and people; they give us the city as a place in the process of change, whose inhabitants were often on the move. Patterns of decline or gentrification are fleshed out and the class vocabulary made more nuanced: the Earl’s Court Road, for example, marked red in 1902, is where ‘doctors and dentists congregate’, while Peckham, its retired shopkeepers hanging on to respectability, is ‘shabby genteel’. The notebooks reveal how readily investigators slid from economic assessment to moral evaluation: ‘The houses have sometimes a furtive secret look, but the evil character of the black streets is rather to be seen in the faces of the people – men, women and children are all stamped with it.’

Booth was an amateur, a successful businessman with a talent for mathematics who funded himself and some members of his team from his private income. The son of the owner of a shipping line, he gradually moved away from the strict Unitarianism of his family in Liverpool, turning to Comte and positivism, a faith in humanity rather than in God. After standing unsuccessfully as a Liberal for the inner city constituency of the Toxteths, he became obsessed with the plight of the poor. His marriage to Mary Macaulay made him part of London’s intellectual aristocracy and the well-connected world of upper-middle-class philanthropists. (Mary’s cousin Beatrice Potter, later Webb, Fabian socialist and co-founder of the London School of Economics – whose academics are responsible for this new edition – was a member of Booth’s team.) Booth was driven by that peculiarly Victorian combination of intellectual curiosity, compassion, a profound sense of moral duty and a ferocious work ethic: he went on running the shipping line during the 17 years of the survey. He was convinced that the new science of statistics would give answers to the question of poverty from which meaningful social policies, rather than palliative measures, might follow.

The poverty surveys displayed, as Morgan remarks, astonishing ‘fieldwork’, but this was not a study shaped by its subjects and, of course, they weren’t consulted about its conclusions. Much of the information obtained was second or third hand. It had to be. Where could Booth’s novice and largely well-heeled team begin except with census material, workhouse registers and interviews with those who knew the poorest families best? They needed guides to take them around the districts. The first survey drew on the notes kept by School Board visitors who chased up children absent from the new ‘barrack’ state schools, and sometimes had the parents prosecuted (those unable to afford the few pennies for attendance were marked as paupers); later reports relied on information from policemen, local clergymen and employers. These experts were hardly neutral and they weren’t always trusted or believed by the team. As the excerpts in this volume show, the guides frequently had to explain the customs of the locals and sometimes to interpret the lingo. Why did every family buy meat to feed their cats when they could barely afford to feed themselves? Affection and the desire to keep down vermin was the surprising answer. Much better, a policeman explained to a note-maker, that a child fetches her father home from the pub for his dinner than her mother, who might stop to down a pint. In a street of housebreakers around Bethnal Green another bobby explained what a ‘fence’ for stolen goods was; Booth, clearly unfamiliar with Cockney rhyming slang, was puzzled by the term ‘tea leaf’.

The nerve of those who braved often hostile terrain is striking, but so is their sense of entitlement. In Clerkenwell, one observer writes, ‘the Italian women are as virtuous as the men are loose’; ‘the general tone of the Isle of Dogs is purple,’ another announces confidently. Individual investigators blamed the poor for their condition and, like most charity agencies and clergy, deprecated handouts or ‘doles’, especially to the able-bodied, believing that they produced shirkers and scroungers. Radically, Booth employed a number of young women as helpers, but their views could be just as astringent. Mary C. Tabor, writing about elementary education in one of the specialist essays Booth commissioned, took a firm stance: ‘The sweet shop is the child’s public house … [It] serves as an excellent training in those habits of heedless self-indulgence which are the root of half the misery of the slums.’

The essays in this new volume have different views on Booth and his survey. Morgan and Anne Power, both of the LSE, salute him as the founding father of social science, the progenitor of socioeconomic modelling of poverty, and of the methods we use to show how modern cities work. Booth’s eight groupings, despite their moralistic overtones, complicated the more absolute and conventional division between the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor. The groupings were arbitrary to some extent and Booth thought there would always be movement between them. Crucially, Morgan and Power argue, Booth saw poverty as overdetermined and not solely the result of individual failings. He identified unemployment, under-employment and low wages as its chief causes and took circumstances – family size, illness, accidents, deaths – into account, as well as the impact of trade cycles. The deleterious effects of alcohol, the subject of feverish moral dispute at the time, ranked low on his list. Booth’s findings led the way for liberals and progressives to argue for more state intervention in public housing, health and welfare.

Other contributors stress Booth’s highly moralised accounts of the economic successes and failures of the working classes (judgments, as Sarah Wise reminds us in her essay on morality, which applied only to the lower orders). Writing on immigration, Katie Garner notes the racialisation of Booth’s categories: his approval of ‘respectable, reliable and industrious’ German butchers, his dismissal of the ‘physically inferior’ lascars and the indolent and troublesome Irish. Hard-working individuals were sometimes singled out for praise, she concedes, but the group they belonged to was demonised. For Wise the survey offers unprecedented access to bourgeois anxieties and values, notably the championing of thrift, privacy and hard work. Those without ambition were beyond the pale. Booth’s bête noire was ‘the loafer’ or ‘the loafing class’, who ‘cannot stand the regularity and dullness of civilised existence and find the excitement they need in the life of the streets’, as he wrote briskly, and perhaps enviously.

‘Disorderly’ is a key term of opprobrium in the survey’s moral lexicon, as it was for the clergy, police and charity workers who helped Booth and his team. Mapping, like the state census, was part of the impulse to order and to make visible and accountable an often transient population. The ‘terra incognita’ of the slums was of course thoroughly familiar to its residents (‘the native takes the back streets,’ one investigator observed, where a gentleman could not follow). The migrants who flooded into London, from other parts of the United Kingdom as well as from abroad, found family or people from home, or workmates or co-religionists, and shared their accommodation. Seasonal workers, who moved in and out of the city, sought out regular local contacts; so did the discharged sailors or soldiers who looked for labouring work at the docks. Jacob Field’s essay on trade, which charts the huge diversity of London’s economy, notes that a hundred-odd markets still existed in the Victorian city, the heart of a social and commercial way of life conducted on the streets. The working classes depended on a face to face economy, on friendly stallholders flogging goods at knock-down prices or willing to sell minuscule amounts by the penny; on knowing where they could pawn their boots or coats every week to pay the rent, or where the best pitches for begging or sleeping outdoors could be found.

The vitality and gaiety of this way of life is captured in the photographs that accompany the essays: sepia portraits of hawkers selling everything from baked potatoes to office stools, a double-page spread featuring pub frontages, shops, cafés and businesses, busy market scenes, several kinds of butcher (this was the great age of meat). The Victorian passion for taxonomy seems to have seized the compilers: varieties of music hall poster are exhibited, mugshots of prostitutes (though these are from Birmingham) and an almost comical spread devoted to 72 cameos of clergymen opposite 84 photographs of London churches, each the size of a postage stamp. Confusingly, the photographs span forty years and are left to speak for themselves. William Strudwick’s ‘Old London’ shots taken in the 1860s show much that had disappeared by Booth’s time: medieval coaching inns and the Lambeth riverside that was destroyed by the Albert Embankment, for instance. In the 1870s John Thomson’s portraits of street people in his monthly magazine, Street Life in London, also recorded worlds and social customs that were fast disappearing. Working alongside the socialist journalist Adolphe Smith, Thomson humanises and even heroicises his subjects, countering the caricatures of Gillray or those Punch cartoons where the poor have simian faces or porcine snouts. Street photography could be used to stir nostalgia or urge the comfortable classes to stump up cash. The pictures were often posed (Dr Barnardo arranged his ‘street arabs’ in before and after ‘reclamation’ portraits). They might also give the armchair slummer a voyeuristic thrill.

Did Booth and his team take vicarious pleasure in the dangerous attraction of low haunts? Unfortunately, the most frequently attributed notebooks in the new atlas are those of George Duckworth. Duckworth is now chiefly remembered as the half-brother who regularly molested Virginia Woolf and was pilloried in her memoirs as a ‘man of pure convention’. From 1892 to 1902 he was Charles Booth’s unpaid private secretary and in his early twenties was a whirlwind of energy. He walked every police beat in the metropolitan area, filling twenty notebooks, equivalent to around two thousand pages, interviewed publicans and picked up local knowledge about crime, police collusion and raids, from local hard men and the constabulary. In the line of duty, he spent a riotous evening at the Eastern Empire, a music hall in Bow, where he noted that the ‘patriotic acts’, aimed at working up jingoism, left the audience cold but the burlesque and comic knockabout had them roaring. He furthered his researches, Inderbir Bhullar tells us in his essay on leisure, at the Battenburg, a gambling club on Goswell Road, but found it sadly dull. ‘A lady at the piano strummed waltzes’ while ‘women of the unfortunate class’ engaged in some ‘mild dancing’.

Duckworth also attended church services. Although Booth’s final seven volumes were headed ‘Religious Influences’, they included evidence about working men’s clubs, music halls and pubs, as well as other sources of social influence. They were also, Aileen Reid argues, his most impressionistic volumes. Her essay subtly evokes a lost world of church attendance and ministry. Despite his agnosticism, Booth held what he called a ‘reverent unbelief’ and felt religion was the only way to change the character of individuals for the better. Though he remained suspicious of ritual, he was in favour of any clergyman who was active or ‘strong’, whose flock was orderly, and who shared a simple expression of faith, whether Roman Catholic, Anglican or Nonconformist. Nonetheless, the survey looked specifically at Christianity. Rabbis were interviewed, but for Booth’s team Jews were largely a social ‘problem’. Judaism, like Islam and Buddhism, was ignored.

Booth’s descriptive passages were as integral to the survey as his statistics. His concern was with the quality of life of those who lived in poverty, and the moral mapping was inseparable from the moral urgency of the project. The poor were never solely a spectacle. Sometimes bourgeois assumptions were challenged. Investigators often noted that dirty and barefoot children seemed happier and healthier than those kept indoors; appalled by the damp, cold, filthy, cramped accommodation they saw, they understood the appeal of the pub. Dissident voices emerge, like that of Inspector Miller in Bethnal Green, who preferred ‘the poor rough’ to the ‘poor quiet’ – they had ‘greater force of character’. The preacher at the Strict Baptists of Streatham was prone to charitable giving without even keeping an account of it: ‘Love for the poor and needy prevails,’ he maintained. Reverend Denison of St Michael’s in North Kensington was not alone in refusing to comply with the survey: ‘I’m not much in sympathy with the tabulating and pigeonholing of our people.’ The tables could be turned altogether. ‘I made my observations at a disadvantage,’ one hapless team member reported: he had cycled through Smithfield meat market in a pair of ‘light woollen trousers’, only to be discombobulated by the porters’ cries of ‘Blimey! Lawn Tennis!’

Booth began his survey during a period of strikes and unrest, not long after unemployed workers had demonstrated in the city on ‘Bloody Sunday’ in November 1887. He believed landlords and employers should act responsibly, but a more radical analysis of a capitalist economy was unthinkable to him. He sent questionnaires to employers, interviewed workers and union representatives, noted wage rates and fluctuations in employment in various trades, but as a supporter of laissez-faire and competitive economic individualism he took a dim view of unions. A few comments surface about corrupt or lazy vestries – the church authorities – ignoring complaints about landlords or being slow in chasing up housing repairs (the Church of England owned a considerable portfolio of slum properties). Some private landlords were also criticised. Infant mortality in Shoreditch, one investigator recorded, was 22 per 1000, much higher than the London average. Quoting an anonymous interviewee, he drew attention to the ‘disgraceful meanness’ of Lord Allington, who owned the whole parish and ‘drew £20,000 from the neighbourhood’.

After the Jack the Ripper murders of the autumn of 1888 the East End, and Whitechapel in particular, became synonymous with extreme violence. Here, surely, was evidence that the denizens of the worst slums were beyond redemption. They were ‘a species of human sewage’, according to the Reverend Lord Sydney Godolphin Osborne in the Times, living in ‘godless brutality’. The murders aroused a terror of the animality that seemed to lurk beneath the veneer of civilisation, and of ‘the dangerous classes’ poised to destroy their betters. Booth disagreed. He had found not ‘hordes of barbarians’ but ‘a handful’, he wrote in his final volume, ‘a disgrace but not a danger’. The incorrigibles of Class A should, he said, be ‘harried out of existence’, but the ‘“casuals” of A and B’ were more of a threat, liable to drag down those immediately above them, sapping the nation’s workforce. His proposals had a eugenicist tinge. He suggested that families could perhaps be fed, housed and put to work in compulsory labour colonies with the sexes segregated to prevent breeding. Right-wingers found this idea outrageous. Any state intervention in the lives of the very poorest was a waste of time and money. And it smacked of socialism.

Booth’s London was far smaller than today’s city and this edition is not entirely user-friendly: the pages don’t follow on like an A to Z (it is far easier – and free – to pore over the digitised versions online in the LSE archive). By 1902-3, the date of the maps in the book, much slum clearance had already happened. In 1900 the Boundary Estate, still too recent to have acquired a colour, had replaced in Shoreditch the notorious Nichol district, sensationalised in Arthur Morrison’s novels as the crime and vice-ridden ‘Jago’. As the new London County Council’s first experiment in social housing, the Boundary Estate was imaginatively conceived, with handsome striped-brick blocks radiating out from a central bandstand and gardens. But few of the original inhabitants could afford its two-bedroom flats, while the absence of sheds or stables, or even useful backyards, excluded the majority who depended on storing goods or keeping animals to make a living. Of the six thousand Nichol residents only 11 moved into the new estate. There were other drawbacks: not everyone fancied being model tenants in these model dwellings with their new rules of respectability – no laundry outside, no ball games, no gossiping, no pets.

On his walk around Holborn, Duckworth observed the ‘general worsement’ near the area being demolished to make way for the new thoroughfare of Kingsway (close to where the LSE now stands). The locals bantered with him. ‘See, he’s taking our pictures, look your best Liza!’ they joked. ‘Don’t pull down our houses Guv’nor before building us up others to go into.’ They knew that rehousing meant unhousing and that what was being cleared was a way of life.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.