Unmounted and unframed, all the Rembrandt prints in the exhibition at the British Museum and all the drawings from Goya’s private albums at the Hayward Gallery – a few hundred sheets of paper, most no bigger than the page of a novel – would hardly fill a modest portfolio. On the gallery walls they draw you forward into exhilarating and troubling encounters. Were images really alive – as one can feel these are – some of the mighty crated works which struggle to get through gallery doors would have to bow down before them.

One slips into anthropomorphism because drawing (in this context it includes etching) is the art which can best show how people react to one another. Before the camera was invented, it was drawing that caught the way a body bends, a head turns, a baby is cradled, a punch is thrown, a figure crumples. Strangers pass in the street impassively: people only become animated when they see a friend, get in a row, are ogled or smiled at. This body language is not primarily a matter of facial expression; and because it has to do with interaction, more than one figure must be there if it is to be understood. When a drawing brings it to your attention you can feel your own limbs begin to try out poses and gestures. Goya and Rembrandt were both masters at recording such moments.

Rembrandt leads people he saw (some come from the street, some from the work of others, some from his own imagination) into scenes from the Bible. Although he made many wonderful prints of landscapes and of single portraits and figures, he was unequalled when it came to showing a crowd. He is democratic. In the Death of the Virgin all eyes, all lines of the composition, point to the pale figure on the bed; the drawing, however, is not more engaged with her lassitude than with the inquisitive faces peering around corners and the eloquent back of the figure who sits reading. In the case of Christ Healing the Sick,(also known as the Hundred Guilder Print) drawings exist which show Rembrandt thinking about the gestures of the invalids who surround Christ: they were not so much studies which arrived at a conclusion that could be copied, as explorations of masses of interacting figures which, on the plate, would be drawn, differently and for the first time.

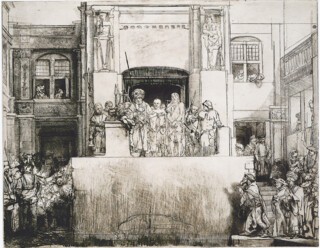

In his very greatest prints Rembrandt produced something no other medium allows. Impressions from different states of a single plate are both new works and part of something larger, which includes what went before. The sheets of paper are the result of a process that has no determined end. In the two most famous examples – Christ Presented to the People and the Three Crosses – the central figure of Christ is the still point around which things are burnished out, and hatching and redrawing take place. The Three Crosses was done entirely in drypoint: that is to say, the image was scratched straight on the copper, not through varnish and then etched. The burr of the drypoint line is quickly flattened in the printing process. The catalogue note suggests that the last version – in which fading lines were strengthened by engraving – was, among other things, a way of getting an economic run out of an inherently fragile plate.* It resulted in an image more mysterious and ominous than the earlier versions, where the surrounding figures – the kneeling centurion, distracted mourners, some of whom seem merely official or curious, can be clearly seen – and is a more direct illustration of the quotation from Luke: ‘Now it was about midday and a darkness fell over the whole land.’

In Christ Presented to the People the change is equally dramatic. A wonderfully lively frieze of ten or so figures gathered below the dais on which Christ and Pilate stand was expunged between one state and the next and replaced by arches which suggest a spring-fed cistern. When you look at the states in sequence it seems as if an official has moved on a distracting crowd which had improperly won your attention.

In this print and many others there is a great difference in the treatment of different groups of figures. Some will be no more than sketched outlines, others fully shaded and detailed. It appears that collectors liked to be challenged; although one contemporary lamented that Rembrandt ‘left many things half done’, in the case of the prints it reinforces the sense they give of art as process.

Obscurity in Rembrandt is physical. In some impressions it is as though he has turned off the light. In one version of the Entombment the surface of the plate as well as the etched lines printed black; only round the figure of Christ and the group beside him has the plate been wiped to allow lines to be read. It is an experiment in how little you need to see to know what is going on, and asks if seeing less might not be to experience more.

Goya’s ‘private albums’ – there were eight of them – were not sketchbooks: they did not contain notes or studies but drawings which could have been (some were perhaps intended to be) engraved in the style of the Caprichos or Disasters of War. With many of the drawings gathered together one can appreciate that each album must have had its own character, must in fact have been an integrated work. Many of the earlier drawings were done with a brush – the lines are straight and swift and without the swing a pen line can give – and economical. Goya observes the sway forward and head-jerk back of a drunk; the determined grip on the ground of the feet of a pair of wrestlers and the way the hands of one claw at the clothes of the other; the bent head of a man trying to get the attention of a baby; the helpless twisting of the bound and gagged woman, a victim of the Inquisition, accused of ‘knowing how to make mice’. His vision is quite unlike Rembrandt’s: emotionally, not physically dark.

The exhibitions complement each other. Neither artist saw us as a pretty species. The sagging flesh and scrawny shoulders of Rembrandt’s nudes make no concessions to the classical ideal. His Christ is neither muscular nor strikingly good looking. He was not the only artist who made engravings of men and women shitting and pissing, but his curiosity about that, and his touching print of a man and woman making love, don’t fit with any view of the human condition which suggests we can avert our eyes from our animal nature. Goya, whose narrow-waisted young women are more stylish than anything Rembrandt did, showed cruelty, deformity, and the pains of disturbed minds more terrifyingly: taking him seriously shakes any confidence you might have in the perfectibility of the species. Rembrandt leaves you with hope, but Goya had a better sense of the terrors we inflict on ourselves and others.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.