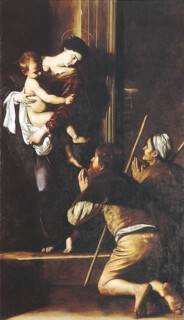

Coming upon the Madonna di Loreto away from its proper home, the Church of Sant’ Agostino, is like finding an old neighbour wandering the streets in bedroom slippers. I saw her in Rome a few months ago. Meeting her in the Royal Academy, where she is one of the greatest of the 15 works by Caravaggio in The Genius of Rome, 1592-1623 (the exhibition runs until 20 April), I felt I should take her by the elbow and see her safely back to the church she was made for. Yet one may never see her so clearly again. Mary, handsome, strong, leaning against the door frame, her great baby, more a child really, balanced on her hip, and the elderly, barefoot pilgrims she looks down at – all well lit, not seen as they are in the church, in the gloom or illuminated by a coin-operated light. And one may never again see the picture in such distinguished company. But if you only see it this way you will have to guess at the presence it has at home.

Loan exhibitions justify such displacements by revealing things not seen or recognised before. In The Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings and the Rise of the Art Exhibition, Francis Haskell, who was chairman of the advisory committee for this show, describes how Old Master ex-hibitions began as more or less random displays of available pictures and only later became more scholarly. Their origins were varied: auction sales in London of pictures that left France after the Revolution; Napoleon’s loot, shown in the Louvre as his campaigns continued; the efforts of clubs of connoisseurs (e.g. the Burlington Fine Arts Club), whose exhibitions were eventually taken over by the Royal Academy; the ambitions of local businessmen, who were the instigators, for example, of the great 1857 Art Treasures exhibition in Manchester; and so on.

Citing the example of Proust rising from his sick bed, for almost the last time, to go and see Vermeer’s View of Delft in the Dutch exhibition held in the Jeu de Paume in 1921 – an experience he worked into the description of the death of the novelist Bergotte – Haskell asks: ‘Does the illumination granted to Bergotte and, perhaps, in different forms, to countless other visitors to countless other exhibitions in various parts of the world, justify the ceaseless growth of a fashion about which we should have serious doubts?’ Those doubts are not just about the physical safety of works of art being made to travel great distances. The big exhibition can draw attention and resources away from the cataloguing and display of permanent collections, as well as making it harder to get scholarly monographs published. Seeing a particular picture in a permanent collection can’t perhaps match the excitement of a loan exhibition, but those few collections – like the Wallace – which stick by the donors’ conditions and refuse to lend, give paintings (many of which were never intended for a specific wall or corner) an assurance of knowing where they belong.

Despite the impressive number of important works by great painters, The Genius of Rome does not enlarge one’s ideas about individual artists. On the other hand, by bringing so many competing pictures together, it gives a powerful sense, hard to get from scattered examples, of the rivalrous excess which, in Rome at the turn of the 16th century, drove the stream of invention into furious eddies. Beverly Louise Brown, who edited the catalogue – seven of the 11 contributors are women: it seems proper that the critical eye cast on what is on the whole male peacocking should be female – cites a description of the atmosphere in Rome around 1604 from Karel van Mander’s Het Schilder-boeck: ‘Mander reports that Pope Clement VIII and various princes had been encouraging the arts through important commissions with the result that artists had begun “to make every effort to reach perfection. A competition begins to see who will run fastest; a new ardour is kindled; lean Envy secretly begins to flap her black wings and everyone strives to do his best to win the coveted prize.”’

Striving is first cousin to showing off. Here you are forced to admire things you may not like: the way the bloom of fruit and the gleam on the belly of a lute are rendered in Caravaggio’s still-life-plus-boy (or boy band) pictures; the way the foreshortened limbs of figures packed tight into a given space fill it with potential energy; the way strong light is used to cast shadows which expunge everything extraneous to the drama – the turning face, the bending back, the foot, the thigh, the hand. The downside to competitive painting is that the pictorial means can distract you from the pictorial end. In the contest painters are tempted to overreach themselves. Caravaggio was the least forgiving – he is like a duellist who draws opponents into confrontations using weapons which he invented and of which he alone is absolute master.

There are other kinds of picture, quite unlike those by Caravaggio and his followers, which figure largely in the exhibition. First there are those with a classical tendency – the Carracci strand – which try to prove that the path Raphael took has not run out. But the high reputation of Annibale Carracci is not explicable on the basis of what you see here: unless you take into account mural decorations, like those he painted for the Galleria Farnese, it is difficult to believe that there really was competition between the school of painters who showed everything and idealised it and the painters who used shadows to wipe out what didn’t matter.

And finally there are small pictures – landscapes with figures – the best by Elsheimer, a sad man from Germany who found painting a struggle, produced little and, still in Rome, died young. These eminently portable works – many on pieces of copper not much more than a couple of hand’s-breadths wide – are decorations for small rooms. Adam Elsheimer tended to choose his subjects from the more obscure parts of ancient mythology and to set them at times of day when sunlight, lamplight and firelight can compete on equal terms. His pictures are full of invention and were admired by Rembrandt and Rubens, among others. Artemisia Gentileschi is inventive in a different way. Her Judith and Holofernes, in which Judith’s maid holds the victim down and Judith dispatches him with the arm’s-length efficiency of a farmer’s wife getting a distasteful barnyard chore out of the way – killing the pig perhaps – is not just realistic about how things look, but about how people look doing things. In this case Caravaggio (whose picture of the subject is also here) is clearly the loser – his Judith looks more puzzled than determined.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.