In 1968, when I was five, my parents moved to Jersey as tax exiles and bought a house in the west of the island. During the German Occupation it had been the site of a slave worker camp. Next door’s garden pond had formerly been the camp’s well, while just over the fence at the bottom of our garden there were grey concrete bunkers covered in brambles and bracken. As children we picked blackberries off them and speculated about what they might contain, but never found a way in. Like our parents, and like many native Channel Islanders, we didn’t give the recent past a second thought: the bunkers, gun emplacements and massive sea walls seemed to have always been there, like the beaches and granite cliffs they overlooked.

Drawing on ‘a wealth of newly released archival material’ and ‘nearly a hundred interviews with islanders and labour camp survivors’, Madeleine Bunting’s book aims to examine the Occupation as ‘a “laboratory” of Anglo-German relations’ and so show how the mainland British might have behaved under Nazism. What makes her account so engaging is the way she lodges it in the present. Noting the diffidence, evasiveness, even fury, she encountered among her informants, she is ‘very conscious that this history trespasses into some of the most painful, hidden parts of their lives’. Having attempted ‘an archaeological investigation into collective memory’, she concludes by challenging the islanders’ ‘failure to remember and acknowledge those who were sacrificed to the islands’ welfare’: that is, slave labourers, Jews and those who resisted or otherwise fell foul of the Germans.

In a pointed prelude to the testimonies of slave labourers, Bunting describes what these ‘nameless and faceless’ thousands left behind; and there, ‘now overgrown with brambles’ or ‘dotted with the brightly coloured towels of holidaymakers’, are my bunkers again. Apparently we had always believed that thousands of slave labourers had died as a result of German brutality, that countless bodies had been tipped into the liquid cement of the islands’ fortifications. Bunting’s 14 witnesses press home the harrowing details. Before long, I was wondering how many skeletons lay concealed in the bunkers at the bottom of my mother’s garden.

Intent at last on excavation, I went to Jersey. I discovered that from January 1942 Lager Udet, the Organisation Todt camp on the site of my childhood home, had housed Spaniards, and from August 1942, Russians and Poles, until the bulk of the OT were withdrawn from the island in the autumn of 1943. The Spaniards, who numbered about two thousand, were Republicans who had fled to France after Franco’s victory in 1939. Later, the Vichy Government had handed them over to the Germans. As conscripted labourers they received the same rates of pay as the volunteers recruited by the OT. They were free in the evenings and on Sundays to come and go as they pleased, to mingle with the local population and visit shops, cafés and public entertainments. Beatings were not part of the routine and they had access to medical treatment – the OT established hospitals, with ambulance services, in all three islands.

As Slavs, the Poles and ‘Russians’ (most of whom in fact came from the Ukraine) were deemed Untermenschen. They were slave workers: unpaid, badly fed and clothed and subject to beatings by OT overseers (there were no SS in Jersey or Guernsey). In all, about fifteen hundred Russians came to Jersey, where the initial death toll was so high that a Red Cross inspection was called for and their treatment improved. Aerial reconnaissance photographs taken in April 1943 show Lager Udet as consisting of 16 large barrack huts with a wired-off inner compound, which presumably contained the Russians – the latter were confined to their camps as a result of thefts of food and clothing from the local population. My bunkers were separate, built as air-raid shelters for the German troop billeted at Hotel La Moye across the road.

The corpses in the bunkers turned out to be imaginary: it would have been impossible to squeeze them through the three-dimensional mesh of steel reinforcing rods spaced at 15 cm intervals in the concrete. Similarly, stories of large numbers of bodies being flung into the sea or into mass graves are belied by the evidence. There are no reports of unidentified bodies being washed ashore. A Commission of Inquiry into alleged mass graves immediately after the war unearthed only drainage systems. And in all the building and landscaping that has gone on over the last thirty years the only skeleton to come to light belonged to a 17th-century donkey. And, in Jersey at least, a wealth of documentation and eyewitness reports testify to the fact that standard procedures were followed in collecting the bodies of OT workers, issuing death certificates and burying them at the Strangers’ Cemetery at Westmount.

This is not to belittle the sufferings of Nazism’s victims in Jersey. It is beyond doubt that individual acts of brutality, even murder, by OT overseers occurred; that working conditions could be perilous; and that the bodies of at least three workers were not retrieved from underneath the rockfalls in which they perished. It is also beyond doubt that in Alderney the inhumane conditions of the slave workers were of a different order from those in Jersey and Guernsey, and that war crimes were committed by officials of the OT as well as the SS, who arrived there in March 1943 with SS Baubrigade 1, a thousand-strong unit attached to the Neuengamme concentration camp.

Alderney was more of a penal colony than an occupied island: the locals had virtually all been evacuated, and it is Alderney that dominates Bunting’s discussion of foreign workers. The title of her chapter on them, ‘Les Rochers Maudits’, extends this French prisoners’ name for Alderney to the Channel Islands as a whole, but the bulk of the chapter – and 12 out of the 14 testimonies – deals with slave labourers’ experiences on Alderney or on their journeys to and from that island. It’s the same when she turns to the post-war investigations of cruelty against the slave labourers. Once again, only labourers in Alderney appear, but Bunting lumps Jersey and Guernsey labourers together with them and misconstrues their rates of death, guessing that between two and three thousand ‘slave labourers’ died in the Channel Islands as a whole. What she has done is to reduce the situation of all OT workers in Jersey and Guernsey to that of the slave labourers in Alderney and represent them as ‘slave labourers’, even though she knows these were a minority among the volunteers, conscripts and POWs in the OT workforce.

Such distortions matter not least because they contribute to the book’s defamatory undercurrent. Bunting insinuates that during and since the Occupation Channel Islanders have been guilty of denying the plight of Nazi victims, for which they therefore bear some sort of responsibility. This is nowhere more apparent than in the one page Bunting devotes to the fate of Jersey’s Jews – or rather the 12 people she claims were registered as such by the Chief Aliens Officer. (Strangely, she ignores the Jews who remained off the record, including the well-known Surrealist photographer, Claude Cahun, alias Lucy Schwob, and her girlfriend Suzanne Malherbe.) Naming Hedwig Bercu and Ruby Ellen Still (née Marks), and apparently unable to discover anything more about them, or indeed the other ten, Bunting resorts to rumour and speculation: ‘It is not known what happened to her [Bercu], although some islanders believe she was captured and sent to a European concentration camp.’ She reports the ‘vague’ words of the then Bailiff, Alexander Coutanche, on the subject: ‘The Jews were, I think, called upon to declare themselves. Some did, some didn’t ... Those who didn’t weren’t discovered. I’ve never heard they suffered in any way.’ A ‘Jersey clerk’, Bob Le Sueur, ‘remembers more’: namely, that Still never returned after being deported and that a Jewish man from Jersey was sent to a prison for the criminally insane where he was atrociously treated. Finally, there are financial details of how businesses belonging to evacuated or otherwise absent Jews were ‘auctioned off’. Thus Bunting leaves us to assume that Islanders quietly laundered their profits and consciences as their Jewish neighbours disappeared into the European Holocaust.

In fact, all the evidence points to the accuracy of the Bailiff’s account. The Jewish businesses Bunting refers to were ‘purchased’, on paper only, by members of staff; they were returned to their rightful owners after the war. Since the book’s publication, Jersey’s local paper has printed refutations of the allegations about Bercu and Still by their relatives and friends, as well as by the Immigration Department, which holds extensive records. Both survived the Occupation. Bercu is a grandmother living in Germany. She ‘disappeared’ in November 1943, not because she was Jewish but because she had been stealing German petrol vouchers. Hidden by islanders until the end of the Occupation, she left Jersey for England in 1947. Still was among the 2200 non-native Channel Islanders deported to internment camps in Biberach and Laufen in Germany. She was reunited with her family in Jersey after the war, where she died in the Seventies aged 84. When I spoke to Bob Le Sueur, Bunting’s main oral source, he was angry at having been misrepresented, and at her failure to check his stories with a better-informed source, whose address and telephone number he even looked up for her.

As my enquiries in Jersey progressed, I encountered an astonishing readiness to talk about the Occupation, a readiness manifested collectively in the extraordinary success of a recent series of lunchtime lectures at Jersey’s museum. Over the last three decades there have been memorials commemorating the Soviet, Spanish Republican, French conscript and Polish dead, and all those who died in concentration and internment camps. Then there is the work of the Channel Islands Occupation Society, whose members have excavated, restored and opened bunkers to the public as well as organising educational meetings and publishing some meticulous research.

Such forms of remembering may be amateur, haphazard, even verging on the idiosyncratic. What makes them so impressive is that they depend entirely on individuals. To expect grand municipal gestures of commemoration or large inclusive histories from such communities is to overlook the Channel Islands’ isolation from the cosmopolitan culture and institutions which feed such expectations: Jersey has no higher education; very many of its graduates fail to return, and since the Occupation its traditional rural population has been increasingly dominated by English incomers attracted by its tax status and burgeoning finance industry. The experience of occupation is a humiliating and degrading one; for people on the Channel Islands it lasted five years and prevented them from joining Churchill’s heroic struggle or basking in its post-war glorification. Such ‘shame’, as Primo Levi calls the malaise felt by survivors of imprisonment, does not parade itself.

There are political reasons, too, why the resistance hasn’t been chronicled more thoroughly – Bunting’s account is itself far from complete or accurate – and why there has been inadequate official recognition of those involved in resistance activities, such as helping foreign workers or running underground news services (in June 1942, the Islands became the only occupied territory where radios were permanently banned). The most successful wartime leaflet operations in Jersey were left-wing and critical of the local administration. They were produced on the former Communist Party duplicator, which was regularly used to print leaflets for the outlawed Transport and General Workers’ Union, the Jersey Communist Party (re-formed in 1942) and the incipient Jersey Democratic Movement (JDM). Towards the end of the Occupation, the duplicator was also used to produce leaflets in German inciting the troops to mutiny. Although it was pre-empted by the Liberation, all the planning and preparation for a local uprising had been carried out, much of it by Jersey’s CP.

The JDM, however, was the real political offspring of the resistance. Set up in the winter of 1942-3, it was committed to campaigning for democratic socialist reform after the war, and for many years it represented the only opposition to the narrow conservative paternalism which still characterises the island’s government. It has also worked politically and practically to improve the lot of Jersey’s Gästarbeiter – originally a French but now mainly a Portuguese underclass employed in the farming and tourist industries. Here, too, there are continuities: prominent JDM members had belonged to the informal network of families who harboured escaped slave workers. Jersey’s post-war government already felt the JDM as a thorn in its side: celebrating its resistance past would have added insult to injury.

After the war, anti-Communist, and especially anti-Soviet, feeling ran as high as elsewhere in the West; and hostility was sharpened when islanders learnt how Stalin had welcomed back the former Russian slave workers they had befriended. Denounced as traitors for having allowed themselves to be captured, they suffered years of persecution. Popular feeling was hardly mollified when it was the Soviet Union, rather than Jersey or Britain, that finally ‘recognised the bravery of the islanders, awarding twenty gold watches in May 1965 to those who had sheltered or fed escaped Russian slave labourers’.

Bunting’s shallow and disappointing ‘archaeological investigation into collective memory’ ends where it might have begun – with Occupation ‘tourism’. As she sees it, the collective memory of the Occupation is hardly different from the selective image peddled by the tourist industry. By way of contrast, she applauds Joe Mière as one of the ‘few islanders brave and honest enough to challenge this sanitised history’. Mière has assembled a collection of photographs and stories of hundreds of Jerseymen and women who variously resisted, fell foul of or even collaborated with the Germans. But the most remarkable thing about his collection is that it is exhibited in the German Underground Hospital. This is now a privately-owned tourist attraction which has been relentlessly tarted up over the years. Its newest, kitschest addition is a purpose-built retail complex called ‘The Sanctuary Visitor Centre & Restaurant’. The old network of bare and chilling tunnels which made me shudder as a child now hosts a series of multi-media ‘experiences’ complete with wax figures, stroboscopic lighting and Jack Higgins voiceover. In the middle of this crass make-believe is Mière’s homemade display: faded photos of people with Jersey names and Forties hairdos, whose quirky captions contain sentiments that are either tender or bitter, but are above all personal. Enlisting Mière as the exception that proves the rule is disingenuous: his accommodation at the heart of the heritage industry subverts any monolithic conception of collective memory.

Tourism is not the only industry to have commercialised the Occupation. There is a long tradition of journalists and self-styled historians arriving in the Islands in search of dirt on it – and being taken far more seriously than they deserved. A writer calling himself Peter Tombs came in the mid-Seventies, promising many of the same sensational revelations as Bunting, only to disappear again when evidence for his allegations failed to materialise. Picking on Bunting is perhaps unfair, for all her British reviewers to date appear to have shared her ignorance and prejudices. No one has been disconcerted by the book’s solecisms, large or small; Hugh Trevor-Roper has called it ‘a masterly work of profound research and reflection’, Norman Stone praised Bunting as ‘a superb chronicler’, Alan Clark admires her ‘careful research’. No doubt her readers have been dazzled, as I was, by her self-confidence. But there are, I think, more profound reasons why no one (in Britain) has rumbled her. First, there is the complete neglect of the Channel Islands Occupation on the part of academic historians. Not a single book, thesis or article by a university historian has appeared on any aspect of it – especially on controversial subjects such as collaboration, resistance, Jews or slave workers. The one reputable account there has been, by Charles Cruickshank, had to be specially commissioned in 1970 by the States of Jersey and Guernsey.

This neglect is part of a much wider aversion to reflecting critically on the war, or on the ‘finest hour’ that was later turned into our founding moment. Myths about British war efforts became a national creed. Their most grotesque proponent was, of course, Margaret Thatcher, whom Patrick Wright once diagnosed as forever ‘redeclaring the Second World War’. Now, however, there is a growing unease about war memory in this country. Evident in last year’s arguments over the D-Day celebrations, it was evident again early this year in the media consensus concerning the anniversary of the Dresden fire-bombing.

As also with the Holocaust. ‘Not our patch’ was how George Steiner caricatured British attitudes towards it only seven years ago. But now it has begun to haunt our patch. The Holocaust is now generally recognised as a specifically anti-semitic programme of industrialised extermination; the paradigm has shifted from Belsen, a concentration camp for slave labourers and Jews in transit, to Auschwitz, a specially designed ‘factory’ for the murder of Jews. Studies of British anti-semitism, and in particular, our failure to help Jews fleeing Nazi persecution, have also spelled out specific historical connections with this country; and what will stick in many people’s minds long after the Second World War commemorations are over will be the images of Auschwitz and the other camps shown almost nightly on television.

For Britons who have become insecure about their moral superiority vis-à-vis the rest of Europe, suspicious of ‘finest hours’ which once unquestionably proved that superiority, and anxious about fitting the Holocaust into their history, the Channel Islands’ Occupation has an obvious appeal. True, it has always attracted curiosity about how Nazi occupation was for ‘people like us’ and has always contradicted Churchill’s boast that ‘we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be.’ Better than Peace in Our Time, Noël Coward’s dramatic projection of English behaviour under Nazi rule – revived for the first time since 1947 to mark the 50th anniversary of VE Day – the Channel Islands offer the real thing: a bit of our patch put to the test of Nazi occupation and found wanting. Bunting and those who think like her make the Occupation into a beguiling morality tale. It not merely provides a justification for their disenchantment with the myths of Britishness which their parents’ generation helped to create: it also offers an expiatory narrative for the guilt engendered by the Holocaust.

‘Madeleine Bunting has travelled to Russia, Ukraine, Germany, France and Belgium to collect the harrowing stories of the former slave workers, survivors of the biggest mass murder ever to take place on British soil.’ Readers enticed by this blurb will not be disappointed by the catalogue of horrors which form the core of the book: what is odd is that no one has questioned it, neither its accuracy, nor, most tellingly, the voyeurism of its compulsive repetition of gory detail. Questioning Bunting’s assumptions about slave workers, Jews and collaboration feels tantamount to heresy; and the national press, notably the Guardian, have treated it as such. The Guardian has continued to give front-page space to Bunting’s ‘new findings’ on Jersey’s Jews, and has failed to publish letters pointing out the distortions and sensationalisations in her account.

Bunting’s self-confessed motto is: there but for the grace of God go I. For all its mock-piety, this is a distancing mechanism: it licenses the projection of British fantasy onto the Channel Islanders and their ‘guilty past’. As Bunting herself observes, ‘British interest in the Channel Islands Occupation is largely motivated by the ways in which it reflects on Britain itself, and by the British preoccupation with its own identity.’ What encourages this is the idea that Channel Islanders are British like ourselves, and that their wartime experience was therefore assimilable to the Nazi occupation of, say, Surbiton. It is perhaps understandable that Hitler’s hogwash about the British racial character led him to ignore the insularity, social and political idiosyncracies and historical isolation which both distinguished the Channel Islands from mainland Britain and set their occupation apart from that endured by other European countries. It is harder to understand why anyone else should share his racist premise. Why can’t we identify with the Danes or even the French, whose occupations offer much apter (and grimmer) models for a hypothetical British one than Jersey’s?

Ironically, Bunting’s book contains the fullest evidence so far of how the Channel Islands were used and abused by the British Government during and after the war. The British authorities bear responsibility for the German bombing raid on 28 June 1940, which killed 44 Channel Islanders and injured another 30: they left the islands undefended and did not inform the Germans that they had been demilitarised. In 1975, Charles Cruickshank confessed his surprise that the British Government ‘got off as lightly as they did for criminal negligence and a cover-up in a big way’.

The British authorities also bungled the evacuation of the islands, and more fiascos followed the German invasion, when Churchill tried to restore wounded pride with a series of costly military raids which achieved little but compromised islanders and caused further deportations. Because their occupation was embarrassing to the Government, the BBC broadcast no messages of encouragement to Channel Islanders as they did to other occupied populations. For the same reason, the Government resisted pressure to send food parcels, although other parts of occupied Europe were allowed them. After D-Day, supplies from France came to a halt, and the islands were under siege from the Allies. ‘Let’em starve. No fighting. They can rot at their leisure’ was what Churchill scribbled in the margin of a liberation plan – and it came to apply as much to the Islanders themselves as to the German garrison. Only in December 1944 did Islanders receive Red Cross food parcels; liberation for ‘our dear Channel Islands’ didn’t come until five months later, when the Germans surrendered on the day after VE day.

Soon after the Liberation, British investigators established that ‘wicked and merciless crimes were carried out on British soil.’ They named five German officers guilty of war crimes in Alderney as still being held in the islands; ten more were known to be in POW camps in Britain; another 31 suspected of war crimes were in the Allied zones of occupied Germany. Britain tried none of them – partly because of its disintegrating relationship with the Soviet Union, but partly also because such trials would have been acutely embarrassing to a government which felt the Channel Island Occupation injured British self-esteem. Since 1946 the British authorities have covered up their failure to prosecute, claiming that none of the suspected war criminals was ever in their hands.

‘J is for Jersey enchained by the foe / And abandoned by Britain in nineteen four 0’ is a couplet taken from an Occupation Alphabet and reproduced in Asa Briggs’s picture book, which coincides with a special exhibition in the Imperial War Museum. Briggs doesn’t discuss this couplet, however, as he does others (on Informers, Black Marketeering and the ‘Jerrybags’ who consorted with German soldiers); he steers clear of the conflicts of feeling or interest between Channel Islanders and the British which arose before, during and after the Occupation. Consequently, he, too, neglects specific issues of British responsibility and overlooks key ways in which the Occupation cannot be assimilated to a hypothetical occupation of Britain. His account is welcome all the same. It is a slight book and contains no original research, but its modesty by and large saves it from error and sensationalism.

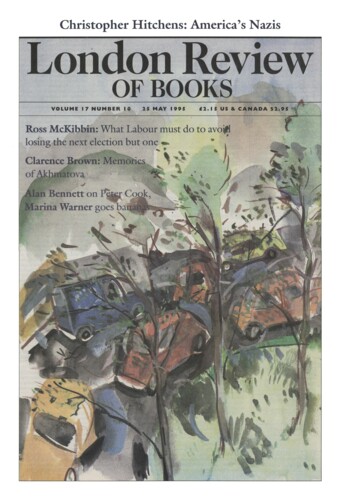

The two books have similar pictures on the cover: in both a British policeman is standing happily beside a Wehrmacht soldier. To contemporary British eyes it is a weird image, both real and unreal, showing an entirely familiar Bobby conversing with a German who could be straight out of any of a hundred cliché-ridden war films. Briggs ‘s cover picture is heavily framed by blocks of lurid yellow, red and black, recalling the German flag. A more effective image for anti-EC propaganda is hard to imagine. This isn’t a nightmare vision of England, past or present, however; its a picture of a specific place in the Channel Islands at a specific moment between 1940 and 1945 (significantly, neither book gives details of where or when these photos were taken). To Channel Island eyes, it depicts a still traumatic reality.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.