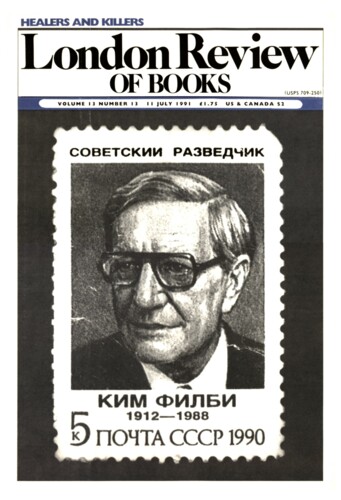

In the international intelligence community, (a loose term to cover spies, spy writers and spy groupies) there are two views on Kim Philby. One is that after he fled to Moscow he was a burnt-out case, a pathetic drunk living on the memory of his great triumph – fooling the West for thirty years. In this scenario, Philby drank to drown the thought of what might have been. If only he had not been so friendly with Guy Burgess, whose follies gave Philby away, he might have become director-general of the British Secret Intelligence Service, Sir Harold Philby, invulnerable to exposure and in a position to have handed the British and American services to Moscow on a plate.

The other view is that Philby’s greatest service to Communism came after he was forced to flee to Moscow, that just by being there he indirectly achieved victories in the intelligence war beyond the KGB’s wildest dreams. Supporters of the second view, and I am one, argue that Philby was instrumental in paralysing Western intelligence operations against the Soviet Union for ten years, that he ruined the careers of some of the CIA’s finest officers, that he neutralised a string of Soviet defectors, caused havoc in the British and French services, and generally undermined the whole conceptual basis of intelligence work.

Philby achieved this by tipping the spy-catcher for the Western world, the CIA officer James Jesus Angleton, into clinical madness. Philby had help, of course. Alcohol, Angleton’s own personality, the very nature of spy-catching, the power of bureaucracies, and the appalling inefficiency of the CIA’s system of checks and controls, all contributed to Angleton’s paranoia. But even Angleton would have had to admit that in Philby’s terrible personal treachery lies the key to understanding both what went wrong with Angleton and what went wrong with the CIA.

Angleton first met Philby in 1944 when Angleton was a raw counter-intelligence officer in OSS (Office of Strategic Services), a gung-ho outfit under the command of General ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan, who thought that the way to win the war was with clandestine groups operating behind enemy lines, a sort of American SOE. Philby was the glamorous, experienced SIS officer. The two worked in the same building in London, and although at that stage they were not close friends, contact had been made – they were on the same side and shared the same aim, the defeat of Fascism. So after the war, when Philby, rising steadily in SIS, was posted to Washington, one of the first Americans he looked up was James Angleton, who was still, like Philby, in the spy business. Philby, after a spell running SIS’s Soviet desk and a tour of field duty in Turkey, was the new SIS liaison officer with the CIA and the FBI, a job that put him at the heart of Western intelligence. Angleton was executive assistant to ADSO (the assistant director of Special Operations) and it was his job to look after Philby and the representatives of other friendly foreign intelligence services. The two men now became close. They lunched together regularly, dined at each other’s houses, met with their families for celebrations such as Thanksgiving. Mrs Angleton remembers them as genuine friends and when I spoke about Angleton to Philby in Moscow in 1988 he agreed that this was so. But all the time Philby was remorselessly using Angleton as his unwitting conduit to the secrets of the CIA. Angleton introduced Philby around, opened doors for him, vouched for him: ‘This is my friend Kim. We knew each other in London.’

When Burgess and Maclean fled to Moscow in May 1951 Philby came under suspicion by association. The reasoning was as follows: ‘Burgess is a Communist spy. He shared a house in Washington with Philby, the crack counter-intelligence officer. If Philby didn’t know, then he is a lousy counter-intelligence officer. If he did, then he is dirty too.’ Angleton would have none of this. He wrote a four-page memorandum to the CIA Director, General Walter Bedell Smith, defending Philby. Philby, Angleton said, had been duped by Burgess and knew nothing of Burgess’s work for the Soviets. He urged the Director to wait; his friend would soon be cleared. A year later, Angleton was still defending him. He told a US foreign service officer he met in Paris that Philby would one day be director-general of SIS.

It was not until 1963, when, with SIS and the CIA closing in on him, Philby fled to Moscow, that Angleton was forced to face the truth – Philby had betrayed him. His first reaction was to cover up. CIA regulations had required that after each official meeting with Philby in 1949-51 Angleton write up a record of what had been discussed. Angleton simply burned these records. But since he was now counter-intelligence chief of the CIA, he could not avoid a damage assessment on Philby. His 30-page report, according to CIA officers who read it, was poorly constructed and very uninformative – ‘an attempt to turn the spotlight away from Philby’. Yet to himself he was forced to admit that everything Philby had learnt about the CIA had come from the very officer whose job it was to protect that agency against this sort of penetration.

Although Angleton blamed Philby personally – he told a friend that if he had been given to murder he would have killed Philby – he also blamed Communism. If devotion to a political cause could motivate a man of Philby’s background to do what he had done, then no one was safe; the Communist menace was everywhere. James Angleton never fully trusted anyone again. On the other hand, the trauma Angleton suffered at Philby’s hands might not have really mattered had other factors not played a part.

All his life James Angleton had a secret – he was half-Mexican. He grew up in an upper-class WASP environment, went to an English public school, spoke with a slight English accent, became more English than the English. He avoided using his middle name, Jesus, because it was Spanish and he became embarassed and angry when anyone found out. ‘The Mexican-Anglo conflict within him,’ his wife says, ‘was very difficult to resolve.’ Since it was his mother who was Mexican, a Freudian analyst would no doubt find things to say about this denial of his Mexican background. Meanwhile, the outward signs were chronic insomnia, rampant alcoholism and a very difficult relationship with his own family.

Angleton worked very odd hours. He seldom arrived in his office before 10.30 a.m. He left shortly after noon for his favourite restaurant, La Niçoise, in upper Georgetown, where he had a regular booking. He drank a Harper bourbon to start, two or three double martinis before the meal, and then bourbon with it. Back in his office, which had no natural light, he often napped much of the afternoon. Then he took home his files and worked and drank through the night. Although this was in that long-forgotten time when heavy drinking was not a medical sin, Angleton’s consumption of alcohol must have been a problem. He drank between 150 and 200 units a week, a unit being a single measure of spirit or a glass of wine. This is nearly five times the point at which current opinion says alcoholism begins. Archie Roosevelt, a CIA colleague, called Angleton ‘a social alcoholic’. A French colleague is more blunt: ‘Angleton was a madman and an alcoholic.’

His married life was turbulent. At the end of the war he volunteered to stay on in Europe for two more years, finding the catching of spies more attractive than life with his wife and baby son. The couple got their marriage together again in 1947, but for the rest of his life it seems that Angleton remained more interested in his job and in his office family. His employees and his colleagues loved him. ‘The thing is he was our one-eyed man in a world of darkness,’ the author of Spycatcher said of him:

We groped but he saw and touched. He became the one man who could interpret the rumours, the innuendoes, the fragments of this and bits of that. We might labour for years on some dreadful and pointless line of investigation and along comes Jim Angleton, he looks at the material and says: ‘Aha! You’ve got something here, Peter. This makes sense to me, even if it doesn’t to you. Thanks very much.’ And off he would go to fit that sliver of information into some horrendously complex pattern. At least that’s what he said he did, and you felt proud and honoured and rewarded for those numbing hours you’d spent on the case. You understand what I’m saying? He gave our work meaning.

In 1962 Angleton’s office family was joined by Anatoly Golitsyn, a KGB officer who had defected the previous year in Helsinki. The two men quickly formed a professional rapport. Golitsyn, a heavy Ukrainian, had hard-line views about the ruthlessness, single-mindedness and Machiavellian cunning of the KGB, against which the flabby Western intelligence agencies were doomed. These views coincided with those of Angleton and when Golitsyn eventually revealed the KGB’s master conspiracy plan, Angleton was all too ready to believe it.

There were two KGBs, Golitsyn said. The West was doing battle with the external one and thought it was coping. But there was another, deeper KGB which was running a long-term operation to destroy the West. The reasoning of the second KGB went as follows. It was useless to devote resources to detecting and catching Western spies sent against the Soviet Union. The West would simply send more. A much better way was to gain secret control of the West’s major intelligence service, the CIA, by recruiting moles among its officers and by sending false defectors. These false detectors could feed the CIA wrong information about the Soviet Union and the moles could report on how this information was being received. Gradually the CIA’s perception of reality could be distorted to suit Soviet aims and the CIA would, in effect, come under Moscow’s control. Once this happened, all the Western spies in the Soviet Union would be of no use whatsoever. The KGB would be running the intelligence world.

Golitsyn claimed that this operation was already under way and that Western intelligence was riddled with Soviet moles. He was too clever to claim that the limited access he’d had to KGB archives before he defected enabled him to name these traitors, but, he said, if allowed to look at the CIA’s files he would be able to identify suspicious characteristics which would point to possibly guilty men. Angleton was convinced, and over the years, thanks to Angleton’s influence in the Western intelligence community, Golitsyn saw the files of the CIA, Britain’s SIS and MI5 and France’s SDECE and DST. It must be said that Golitsyn had some successes in providing clues that helped identify such spies as the Admiralty clerk William John Vassall; Georges Paques, a French officer in Nato; and Hugh Hambleton, a Canadian professor. But although he insisted that there must be moles in the CIA, he never found one. Instead, over the years, his list of suspects in the West became more and more outrageous. They included Harold Wilson, Olaf Palme, Willy Brandt, Armand Hammer, Averell Harriman, Lester Pearson and Henry Kissinger. They also included every Soviet defector who had come after him. These men had been sent, Golitsyn said, to discredit him because the KGB knew how dangerous he was to their master plan.

By the time he got round to the case of Henry Kissinger as a KGB mole, Golitsyn had brought Angleton into his paranoid world and the two men were feeding each other’s illness. Dr John Gittinger, the chief psychologist of the CIA’s Clandestine Services, examined Golitsyn: ‘There was no question in my mind,’ he concluded, ‘that Golitsyn was paranoid, that he was mentally ill … I find it amazing how much of what he said was accepted. It remains incomprehensible to me.’

Together, Golitsyn and Angleton proceeded to tear the CIA apart. During the crucial years of the Cold War – the U-2 crisis, the Berlin crisis of 1961, the Cuban missile crisis, the Middle East wars – Angleton, acting on Golitsyn’s advice, rejected at least 22 Soviet defectors on the grounds that they were ‘dirty’. The CIA and the FBI have since established that every single one was genuine. In roughly the same period, Angleton’s hunt for Soviet moles within the CIA led to the investigation of 40 senior officers, 14 in depth. Some FBI officers believe that at this time the FBI was following more CIA officers in the United States than KGB agents. Careers of good men were stalled or ruined and reputations smeared, often without the officer concerned having any idea why. Yet not one of Angleton’s leads matured, not one single KGB penetration was uncovered, not one prosecution launched.

In truth, Angleton was ill-equipped for his job. He did not speak Russian, he had never been to the Soviet Union, he had never run an agent, and he had no idea what it was like in the field. When his successor went through Angleton’s office, he came across safes that had not been opened for ten years, files that had slipped behind a cabinet five years earlier, a huge safe known to Angleton’s staff as ‘Grandpa’ which turned out to contain – when finally opened by the CIA’s safecracker – papers from British Intelligence and files on journalists who had worked in Moscow. None of this material not that from any other Angleton archives was logged on the CIA computer because Angleton refused to have anything to do with a technology which might allow someone else access to his secrets.

It is tempting to regard the whole story as an enormous joke, an intelligence fiasco scripted for Monty Python. But when we consider the power Angleton and Golitsyn had over people’s lives, the laughter fades. They caused one KGB defector, Yuri Nosenko, to be illegally held in CIA prisons in the United States for five years, while they tried to make him confess that he was not genuine. For much of this time, Nosenko was kept in a small windowless room, where he was poorly fed, allowed no cigarettes, no toothbrush or tooth paste, no radio, television or reading matter, and only one shower a week. He was subjected to frequent hostile interrogation and liedetector tests, verbally abused, and, Nosenko says, given hallucinogenic drugs.

When the CIA eventually cleared Nosenko, apologised to him, rehabilitated him, employed him, and helped him get his US citizenship, Nosenko looked up Angleton’s home telephone number and called him from a public phone. He asked why Angleton had never had the courage to meet him face to face. Angleton, Nosenko says, was unrepentant: ‘I’m standing strong on my position,’ he replied ‘This is how I advised the Director and I’m not changing my mind. I have nothing more to say to you.’

Ingeborg Lygren, a quiet, middle-aged woman, was a trusted translator on the staff of Colonel Vilhelm Evang, head of Norway’s Military Intelligence Services. The CIA arranged for her to serve in Moscow as a ‘go-between’ for the CIA’s agents submerged in the Soviet Union and she did this successfully from 1956 to 1959. Five years later, Angleton and Golitsyn, rummaging through their files in Washington, became convinced that Lygren was a KGB spy. On their urging, the Norwegians arrested her, charged her with spying for a foreign power, and sent her to Bredtvedt Women’s Prison. There she was held in solitary for three months and endlessly questioned by tough professionals who exposed each intimate strand of her sad and lonely life. At the end of the three months the state prosecutor reviewed the evidence, promptly threw out the entire case and ordered Lygren freed immediately. It was too late. She had had a nervous breakdown in prison. Something in her had snapped and she was never the same again. When Angleton’s successor reviewed the case, he decided that Lygren had been completely innocent and should be compensated. He sent a CIA officer to Oslo with authorisation to give Lygren a quarter of a million dollars. The officer made the approach through a senior Norwegian civil servant but was told: ‘I have taken the precaution of asking Miss Lygren about this before you came today. She would no doubt thank you for your offer, but she has indicated that she does not wish to meet you or to receive any money from your organisation.’

The crucial question in the Angleton story is how could it ever have happened? The answer is that the secret world encourages people like Angleton. It finds them, nourishes them and promotes them in the mistaken belief that it can control their obsessions. But then the bureaucracy of the intelligence agency defeats such control. The compartmentalisation, the ‘need to know’ principle (no one is ever told more than he needs to know to do his job), makes it difficult to detect that a senior officer has Surrendered his hold on reality and is operating in a world of fantasy. And the higher such a person rises in the agency, the more difficult it becomes for anyone to point this out, until, eventually, they become unassailable.

When Angleton was at his peak, the CIA ran a system of ‘GS’ (General Service) rankings. The vital step in an officer’s career was the jump from GS-14 to GS-15. This required the unanimous approval of a special promotions board on which Angleton sat. He had the power to deny promotion to any applicant on security grounds. So no officer was willing to risk his entire career by criticising or antagonising Angleton. In 1974 William Colby, as Director of the CIA, sacked Angleton. None of his predecessors had paid proper attention to what then counter-intelligence chief was doing. This excellent book confirms what I have long believed: that all intelligence agencies, no matter what controls they appear to work under, are a danger to democracy. In an unguarded moment before his death in 1987, Angleton told – and later tried to retract – the truth: ‘It is inconceivable that a secret intelligence arm of the government has to comply with all the overt orders’ of that government.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.