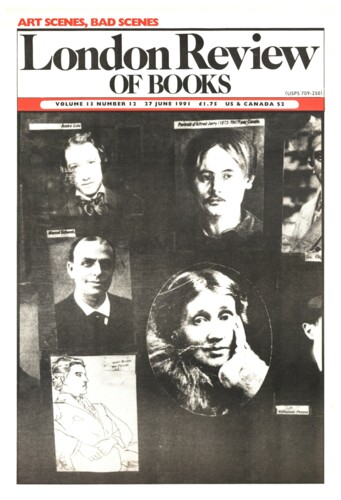

John Minton’s face is familiar – if not from the self-portrait now in the National Portrait Gallery, then from the likeness he commissioned from Lucian Freud and bequeathed to the Royal College of Art. It is very long, large-eyed, hollow-cheeked, with a receding chin and dark tousled hair. Photographs suggest that the self-portrait is a better physical likeness; the truth about his emotional state seems to lie with Lucian Freud. The manic side of his personality shows only in photographs, where the mouth stretches into a toothy grin. His work, once famous, is now probably best remembered by those who saw it when it first appeared in Penguin New Writing, or on book jackets and in magazines.

Frances Spalding’s biography gives us the life with too many adjectives but an abundance of facts and first-hand accounts. She is tentative about the value of the work, which is understandable, and about the man, which seems unkind. The facts are not so remarkable as to be worth exhuming for their own sake; without generous feeling for him or for what he made, the biographer becomes voyeur.

Minton was one of the victims of Soho-Fitzrovia, and one of its stars. In the sober Nineties it seems to be difficult to look back with any degree of enthusiasm, and without condescension, to the last English Bohemia, in which Minton was far from being the only considerable talent drinking itself to death. The ‘Roberts’ (Colquhoun and MacBryde) were there beside him; Dylan Thomas was boozing in the same pubs. Art is not made in that spirit any more. The notion that all things are a gamble, that candles should be burnt at both ends, that poverty is often art’s handmaid and scrounging talent’s privilege does not come to your mind these days as you walk up Cork Street. And yet Soho’s survivors – Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, even Jeffrey Bernard to name three who appear quite often in Spalding’s book – show what can be won by sticking to your line. What they do now and did then is more interesting than what a lot of people who thought they were overtaking them in the years between have managed.

Reading the funny letters Minton wrote, and applying their tone of voice to the things people who knew him remember, makes it clear why he had many friends, and why his downward spiral into alcoholism, and depressions which were exacerbated by unsatisfactory love affairs, saddened them. There may even be a little guilt in it. Every time and place has its characteristic luxuries. In Minton’s Soho they were champagne and taxis. Minton was always better off than most of his friends, and sometimes very much richer (the money came from department stores, not china); he bought his own good times, which often meant buying them for other people as well. It would make no sense to ask who among the taxiloads of sailors, students, painters, writers and boozers he transported from bar to bar were the exploiters and who the exploited, but, as the quotations about good times and good fun fade into descriptions of Minton’s bad times, the question ‘could we, should we, have done something?’ seems to lie about in the memoirs of his friends.

Minton had plenty of personal problems, and professional doubts as well. But if he had begun working in the Sixties, when overtly homosexual subjects had become more acceptable, his imagination might have developed differently. As it is, he became a wonderfully good decorator of pages who was for ever dogged by the idea that he should do something more than exploit a talent to please. His drawings are well-mannered; they decorate without intruding. He wonders in a letter to a friend what housewives make of his sailors, like the one who leans on a table spread with good things in Elizabeth David’s Book of Mediterranean Food. The housewives doubtless thought they were nice lads; in life and art the physical types which attracted Minton were butch. The boys in Hockney’s Cavafy illustrations would not have stepped so easily or so politely onto Mrs David’s pages.

Both Minton and his contemporary, Keith Vaughan, have found biographers, but have not been given full-blown picture books. On the other hand, literary memorials – the opening chapter of Brideshead Revisited, Elizabeth Bowen’s descriptions of London, even stories by Walter de la Mare – could be taken as appropriate starting-points for a journey into the neo-romantic visual art of England in the Thirties, Forties and Fifties. Minton’s drawings make a romance of the facts of wartime England: ruins, deserted docks and bombed buildings, and of nostalgia for the South, the Mediterranean, the insular wartime dream of Continental pleasures in which olive oil drips in golden streams and lobsters and mussels nudge strings of garlic and piles of melons. The sources of his style were there in the Thirties: Sutherland’s spiky way of drawing spiky things from which Minton removed much of the threat; romantic mountebanks from Tchelitchew and blue-and-pink Picasso which he made less melancholy-histrionic. His atmosphere is a little thunderous, but not to the point of Mannerism, nor are his figures as stagey-grotesque as Michael Ayrton’s were. His line and colour are tart – compared with illustrations commissioned for cookery books today, almost brutal – but the world they create is welcoming.

Before market research quantified the effectiveness of commercial art, and fine art became too rich, proud and personal, such things were done. The patronage of Shell, the Underground, the odd restaurant and a few publishers and printers allowed Sutherland and Piper (and other drier, more sprightly and journeyman-like talents, Bawden and Ravilious, for example) to develop mannered, pleasantly melancholy and cheerfully grotesque styles of illustration. They did not have the kind of popularity which dominates a mass market, but they gave the client’s product a touch of class. The BBC, before it knew what a ratings war was, and Vogue, before the advertising pages got to be smarter than the editorial ones, used them. Minton was briefly one of the frail pillars of that universe of good taste, which got its final comeuppance when the vitality of the genuinely popular arts made the notion of the improvement of taste seem an absurd condescension. Even Pop Art was still fine art going popular, but Peter Blake’s and David Hockney’s mature commercial appearances rated star billing and held their own in record stores and poster shops.

Minton did not have Piper’s or Ravilious’s Betjemanesque delight in the look of England, but his Death of Nelson, which at first glance seems to hark back with mad presumption to David and Géricault, was in fact derived from one of Maclise’s murals for the House of Commons. It is not very clear what Minton thought he was up to, but he doesn’t seem to have been joking. Perhaps it is best to think of the Death of Nelson as popular art, like Staffordshire figure groups of the same kind of subject.

Minton’s most ambitious paintings failed; his most perfunctory decorations and illustrations often succeeded. The reasons are not easy to disentangle. To say that his big pictures – the Death of Nelson, Coriolanus, even the Death of James Dean – look like enlarged illustrations is unfair to his real illustrations. He was delighted when he found he could use a big photograph of a drawing on an exhibition stand, and was right to be. His pen marks were much more interesting than his brush marks and stood up to enlargement very well. His portraits of young men, often lovers, might be expected to project the feelings he had for them. They do not. If he had been able to make pictures which were in some sense confessional or autobiographical, as his contemporaries Freud, Andrews and Bacon did, he might have defeated the self-loathing which eventually brought him to self-destruction.

Success did not desert him; to the end he got commissions and kept his deadlines but he drank more and more and liked himself and his work less and less. The illustrations do not show a marked decline; an illustrator’s style, once perfected, is, like handwriting, hard to destroy. Those painters who manage to go on developing over the long haul of a lifetime are different; their way demands a greater degree of self-sufficiency and depth of talent than Minton had. He was also sharply aware of how things were changing, of abstract painting pushing figurative painting to the margin. As a teacher he was out of sympathy with his students, who said in an open letter to him, published in 1956:

We are not disillusioned with the world. There is no God that failed us. To your generation the Thirties meant the Spanish Civil War; to us it means Astaire and Rogers. For you ‘today’ suggests angry young men, rebels without causes; we believe in the dynamism of the times ... Our culture heroes are not Colin Wilson and John Osborne, rather Floyd Patterson and Col. Pete Everest are more likely candidates for the title.

Painful stuff, one imagines, for a man who knew what it was to be fashionable.

Keith Vaughan had plenty of self-loathing, but more self-confidence (or a less painful kind of self-awareness) and a dour tenacity. His paintings, some more, some less abstracted, owe most to Cézanne but reduce Cézanne’s battle with appearance, solidity and the autonomous life of the picture’s surface to something much nearer a decorative formula. That Vaughan should eventually have followed de Staël into an abstraction which combines suggestions of the appearance of things with an attractively painterly surface seems, in the context of his avowed admiration of Cézanne, to be a betrayal not an advance.

In 1952 Christopher Isherwood gave E. M. Forster two bottles of claret and a painting by Vaughan. His work made an ideal gay to gay present; the male nude, or nude in landscape were his main, almost his only subjects, and the steady sale of his smaller works seems to have had a lot to do with this. His figure subjects are as impersonal as representations of human beings can be: the heads are often very small rectangular extensions of the torso, miniaturised Ned Kelly helmets, as it were. Vaughan never, it seems, got his sexual and emotional lives together and it is hard not to read into the facelessness of so many of his figures a commentary on (for example) the irritable and unsatisfactory relationship he had with Ramsay McClure. Despite Vaughan’s note – written when McClure was in hospital suffering from tuberculosis – saying, ‘simply to avoid any misunderstanding by my future biographers I wish to say that all previous remarks regarding R are null and void, as void as the heart that wrote them,’ Yorke remarks that when McClure returned from hospital he had to realise that the machine, bought from Gamages department store, ‘which could be adapted to pass electrical currents through the genitals’ was now ‘his greatest rival for Keith’s time and affection’.

When one looks at them now, Vaughan’s paintings seem to have the virtues and vices of tastefulness. The colours: browns, greens, black, white and a pretty Gauloise blue are decorative, the shapes of bodies make hand-some patterns. But the effects seem too easy. It is as though, relieved that the freedom to distort form and invent patterns had been won by his masters, Vaughan hoped that the task of consolidation would be his. Things never work that way. After visiting the first New Generation exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1964, where English painters of the generation after his – some Pop, some abstract – got a wide showing, he wrote, ‘I look at my work – the result of some forty years’ effort and hope – and at theirs – the result of five or six at the most. And it’s I who feel defeated. Because all the values I’ve lived for now count for nothing.’

Although Vaughan and Minton shared a house in Hamilton Terrace for six years and came from similar middle-class backgrounds, they irritated each other. Vaughan could both envy and despise Minton; he was the small brown bird and Minton the parakeet. In his journals (often written when drunk at the end of the day) he comes across as a depressed rather than a depressing figure; for a man who always seems to have waited for invitations rather than given them he had a rather successful social life. As he grew older, younger men whom he liked (Hockney, Patrick Procktor among others) seem to have found his company agreeable. But there are too many notes of nights with the auto-erotic device and the whisky bottle for his last entry, written while waiting for his overdose to take effect, to seem entirely what, in part, it was: an admirable act of will in the face of terminal cancer.

Both he and Minton had a notion of success which depended on feeling themselves to be proper painters. They wanted the support of a tradition in which they could be seen to have an acknowledged place. That other events – the rolling-by of the Abstract Expressionist juggernaut and the opening of the Pop side-show – drowned the voices of so many English painters of their generation is ironic when one considers how good they were with words. Ayrton was a novelist as well as a critic, Patrick Heron is a critic as well as a painter; Minton’s pronouncements on art, like Vaughan’s, are lucid and perceptive. The war, which diminished opportunities to paint and exhibit, also brought isolation: cut off from Europe and America, a purer breed of British painting seemed possible. As it turned out, the strain of the native race represented by the early work of Vaughan and Minton was not as vigorous as the hybrids which renewed contact produced. The careers of Moore and Sutherland (like those of Picasso and Matisse in France), completed their trajectories, unaffected by the American influence: in England the traditionlessness and energy Minton’s students responded to in their American heroes was to be effective for the next decade. The sadness which both these books exude is not so much of wasted talent as of the failure of talent quite to match up to what intellect so clearly saw was the task at hand, and the failure of history to give them time to thwack what had seemed such a promising ball down the fairway of the future.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.