The Greeks had a saying that ‘the iron draws the hand towards it,’ which encapsulates, as well as anything can, the idea that weapons and armies are made to be used. And the Romans had a maxim that if you wish peace you must prepare for war. Oddly enough, even strict observance of this rule is not always enough to guarantee peace. But if you happen to want a war, preparing for it is a very good way to get it. And, among the privileges of being a superpower, the right and the ability to make a local quarrel into a global one ranks very high. Local quarrel? Here is what the United States Ambassador to Iraq, Ms April Glaspie, told Saddam Hussein on 25 July last:

We have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait. I was in the American Embassy in Kuwait during the late Sixties. The instruction we had during this period was that we should express no opinion on this issue, and that the issue is not associated with America. James Baker has directed our official spokesmen to emphasise this instruction.

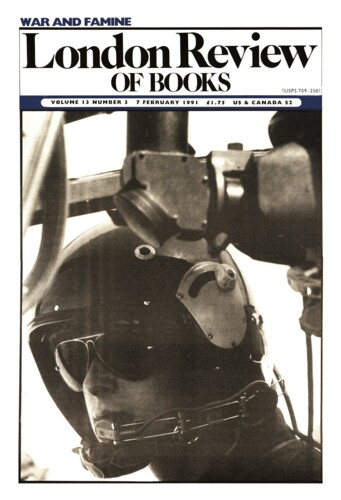

Even as the latest in ‘smart’ technology grinds and punctures the Iraqi military, this amazingly explicit enticement to Saddam is still being debated. Did the United States intend to keep Iraq sweet by giving it a strategic morsel of Kuwait and access to the sea? Or did it intend to remind its Gulf clients that only American umbrellas could protect them from Iraqi rain? Or did it perhaps intend both? Those who think this too cynical might care to remember that Washington incited Iran to destabilise Iraq in 1973, and Iraq to invade Iran in 1980, and sold arms on the quiet to both sides throughout. As Lord Copper once put it, ‘the Beast stands for strong mutually antagonistic governments everywhere. Self-sufficiency at home, self-assertion abroad.’

Considerations of this kind tend to be forgotten once war begins, but one day the swift evolution from Desert Shield through Imminent Thunder to Desert Storm will make a great feast for an analytical historian. For now, everything in Washington has narrowed to a saying of John Kennedy’s, uttered after the Bay of Pigs, to the effect that ‘success has many fathers – failure is an orphan.’

The debate in Congress, which was very protracted and in some ways very intense, was in reality extremely limited. The partisans of the Administration said, ‘If not now, when?’ and their opponents replied: ‘Why not later?’ The partisans of the Administration said there would be fewer body bags if Saddam was hit at once, and their opponents replied feebly that all body bags were bad news. Only Senator Mark Hatfield, the Republican from Oregon, refused either choice and voted against both resolutions. In his speech announcing the immediate exercise of the powers Congress had conferred on him, Bush oddly borrowed a phrase from Tom Paine and said: ‘These are the times that try men’s souls.’ This line actually introduces Paine’s masterly pamphlet ‘The Crisis’, and goes on to talk scornfully of the ‘summer soldiers and sunshine patriots’. In the present crisis, with the hawks talking of war only on terms of massive and overwhelming superiority, and the doves nervously assenting on condition that not too many Americans are hurt, almost everyone either is a summer soldier or a sunshine patriot.

This is true even of the surprisingly large ‘peace movement’, which has spoken throughout in strictly isolationist terms. True, there was some revulsion at the choice of 15 January for the deadline, because it is the officially celebrated birthday of Martin Luther King and many felt that Bush either knew this and did not care or, worse still, had not noticed. But, except for a fistful of Trotskyists, all those attending the rally in Lafayette Park last weekend were complaining of the financial cost of the war and implying that the problems of the Middle East were none of their concern. I found myself reacting badly to the moral complacency of this. Given the history and extent of United States engagement with the region, some regard for it seems obligatory for American citizens. However ill it may sound when proceeding from the lips of George Bush, internationalism has a clear advantage in rhetoric and principle over the language of America First. The irony has been that, in order to make their respective cases, both factions have had to exaggerate the military strength and capacity of Iraq: Bush in order to scare people with his fatuous Hitler analogy, and the peace camp in order to scare people with the prospect of heavy losses. Therefore, as I write, American liberals are coming to the guilty realisation that unless Saddam Hussein shows some corking battlefield form pretty soon, they are going to look both silly and alarmist. Surely this cannot have been what they intended?

Conor Cruise O’Brien once told me that when he took the Irish chair in the United Nations, Ireland having joined rather late, he found his delegation seated alphabetically next to Israel. The Dublin delegates were overwhelmed by the warm hospitality displayed by their Jewish neighbours, who were almost embarrassing in their effusiveness. Only after a while did they realise that before Ireland’s accession Israel had been sitting next to Iraq. Then came the grim day when O’Brien and his Israeli counterpart, Gideon Raphael, watched their mutual friend Adlai Stevenson trudge through a mendacious speech about that same Bay of Pigs. He knew he was lying, they knew he was lying, he knew they knew that he knew. As a consequence, he would sometimes lift his eyes to where they sat, as if in mute appeal for them to realise that he hadn’t written the damn speech. And as a secondary consequence, he muffed his lines. Concluding the Administration’s case against Castro for his ‘crimes against man’, he repressed a sigh and turned to his ‘crimes against God’. Glancing up again to where his friends sat, he grotesquely misread: ‘Fidel Castro has circumcised the liberties of the Cuban churches.’ Raphael turned to O’Brien with a classic shrug and muttered: ‘I knew we’d get blamed for this sooner or later.’

The line between self-pity and self-mockery in that case was very well drawn. Better than it is today, at any rate. It has been doubly unedifying to see Bush pretending that he has never met an Israeli in his life, and the Israelis pretending that a war between America and Iraq has nothing to do with them unless they are attacked. The element of ‘denial’ here is what lies behind the refusal to consider ‘linkage’. In a region so thoroughly and multiply imbricated, ‘linkage’ is no more than an everyday term for common sense. Obviously, a solution to the Palestine question would help compose most of the regional disputes. No less obviously, the United States was committed to this view of the matter well before it gave Saddam Hussein the green light to invade Kuwait. Nor does his exorbitant interpretation of that green light make a settlement of the Palestinian question, or the suddenly-discovered problem of nuclear proliferation, for that matter, any less urgent. Yet Bush’s refusal to consider an international conference is in itself a negative ‘linkage’, because it predicates a future discussion of peace on a current conduct of war instead of the other way round.

One ‘linkage’ that is scarcely ever mentioned here is the adamantine link that binds John Major, via the Desert Rats, to Desert Storm. It is easy to find news of the French, the Kuwaitis and other participants in Bush’s international brigade – or is it General Schwartzkopf’s, since Bush, in a chilling moment, announced that he would leave the conduct of the war to the military? Of the poor Brits, we hear barely a squeak. It was the same when Major came to Camp David just before Christmas – he could as well have been travelling incognito. I think myself that Mrs Thatcher grew so sensitive to the cry of ‘Reagan’s poodle’ that she never failed to give tone and colour and visibility to the favours she undertook for Washington, even if she was bound to perform them anyway. She also very seldom neglected to ask for something in return. Major is more like a traditional Labour prime minister (or opposition leader) eagerly assuring the Americans that they can count on him no matter what. That of course is just what they then proceed to do. Had I the ear of Mr Major I would urge him to be a touch more theatrical in his declarations with possibly the teeniest bit of reservation tossed in. There’s more joy in heaven that way, and a touch more respect too.

The night before the bombers left their Saudi and Turkish airfields, I was faxed the following appeal, which didn’t make it into any American newspaper. Addressed to Perez de Cuellar (or Pair of Quaaludes, as he is known in Washington), it called for an international conference on the Baltic states and an extension of ‘the deadline for UN Resolution No 678 of 29 November 1990, relating to the Persian Gulf crisis’. Signed by the presidents of the republics of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, and by Boris Yeltsin on behalf of the Russian Federation, it ended very simply by saying: ‘We hope we will be understood.’ Here is another ‘linkage’ which George Bush can scarcely affect not to comprehend, though it seems he took no notice at the time. Perhaps it would have been harder to dismiss such an appeal as a call for ‘appeasement’. It was as a consequence of Munich, after all, that the fate of the Baltic republics was sealed in the first place. Concentration on the Suez-Hungary precedent of 1956 may obscure the fact that an opportunity exists now that did not exist then. The Soviet Union has colossal oil resources, which it needs technical help to exploit and develop. If the United States were not so obsessed by its imperial control of Arab oil, it could be evolving a longer-range policy of enriching both former Cold War antagonists by investing in and purchasing Russian oil and, as part of the bargain, insisting on respect for majority rule in the Baltic. More than one chance has therefore been missed by giving another wrench to the spiral of resentment and dependence in the Middle East, while awarding a freer hand to the Soviet military-industrial complex. ‘Only connect’ is still a better motto than ‘no linkage’.

Talking of links means talking about Cable News Network, Ted Turner’s amazing practice of his ‘One World’ principles via an Atlanta, Georgia satellite company. (Last year, he issued an instruction that his newscasters refer to ‘international’ rather than ‘foreign’ news, and he may be about to induce the Government of Vietnam to permit him a relay station.) Until Saddam’s ruffians cut off the line, Peter Arnett, the intrepid New Zealander who must now be the world’s senior war correspondent, was providing actuality from Baghdad. I once met Arnett and was fascinated to learn that it had been he, interviewing the American officer in charge of the Ben Tre region of Vietnam in 1968, who had been unironically told that ‘we had to destroy the town in order to save it.’ One of the greatest unforced wartime scoops, this line is bound to recur in consciousness as one watches America yet again trying out new weaponry.

Unlike Vietnam, Iraq is neither ethnically nor politically homogeneous. If its infrastructure and psyche are badly torn, it has the recognised potential of becoming another Lebanon, with Sunni, Shi’a and Kurd making up for lost time. As with Lebanon also, neighbouring countries might interest themselves in the turmoil. Syria would undoubtedly do so, newly emboldened by its vast subvention for opportunistically joining Desert Storm. Iran would be unlikely to resist the chance to break the stalemate of 1988. And from Turkey come irredentist calls for a move on the Iraqi oilfields around Kirkuk and Mosul. (Hussein is right about the ‘colonial’ border with Kuwait, but all the borders of Iraq are colonial if it comes to that, and liable not to be respected in their turn.) The Turks might remember that Kemal Ataturk did not want the Kirkuk and Mosul fields when the borders were first being drawn. Possession of oil was tempting, he said, but it was also tempting to outside powers, and the country which had it might lose its independence and its soul. What a curse the stuff is, and how wretchedly distributed. Arab nationalists are rightly fond of recalling the glories of Arab civilisation, but these glories pre-date the discovery of the region’s greatest resource. How this affects the materialist conception of history I’m not sure for the moment, but the elements of Edward Said’s recent marvellous lament for the odiousness of inter-Arab politics can all be traced to oil and its predators.

Not that the region was free of curses and plagues in earlier times. I was more than usually depressed to see that, the night before unleashing Desert Storm, George Bush had a prayer meeting with Billy Graham in the White House. Every time that a conflict impends in any formerly Biblical land, this elderly nuisance starts drivelling about the last days and the end of time, and the Christian Broadcasting Network (which still feeds an astonishing number of American homes despite Ted Turner’s Trojan exertions) starts to run the Book of Ezekiel in prime time. It’s always been a source of perplexity to these already perplexed characters that, however interpreted, none of the ancient prophecies ever mentions the United States or anything that could remotely be construed as prefiguring it. That’s why it was unfair of me to mention the Beast at the outset. But perhaps Bush’s locutions contain a clue. While everybody else refers to the real Beast – the Baghdad and Babylon beast – as Saddam, the President doggedly calls him Sodom.

We appear to live in a time when things that were once unthinkable come to seem inevitable. I have believed in the certainty of a Gulf War ever since last November, when I stood on the tarmac at Dhahran in Saudi Arabia and heard Bush tell his troops that he, like the peaceniks, wanted them home soon but thought the quickest way home lay through Iraq and Kuwait: all empires learn that it is very unwise to make false promises to the soldiery, and Bush certainly kept this one. But I am to this day unsure of the motivation. There were a thousand ways for a superpower to avert war with a mediocre local despotism without losing face. But the syllogisms of power don’t correspond very exactly to reason. It now emerges that there had to be an assault in mid-January because the weather was about to turn nasty, the pilgrimage season was about to begin, the cost of maintaining idle forces was too high and, as the Boston Globe put it in a story on the budget last month, ‘Administration economists admit their projections assume a quick, clean finish to the Persian Gulf crisis, probably by March, and concede that if anything else happens the country’s economic troubles will deepen.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.