Two major security challenges confronted the Israeli government headed by Yitzhak Shamir in the second half of 1990: the Palestinian uprising, now in its third year, against Israeli rule in the occupied territories, and the crisis triggered by Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait on 2 August last year. To begin with, the Gulf crisis overshadowed the intifada, but within a short time it also contributed to a serious escalation of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, pushing it to the brink of an inter-communal war. Increasingly, the solution to the Gulf crisis became linked in the public debate with a solution to the Palestinian problem, giving rise to a new buzz word – linkage.

At the helm in Israel during this turbulent period has been the most hawkish right-wing government in the country’s 42-year history. Shamir’s Cabinet is more purely right-wing in its composition than the Menachem Begin Cabinet of 1977 which achieved the peace treaty with Egypt, or even Begin’s second Cabinet, which took the decision to bomb the Iraqi nuclear reactor, formally annexed the Golan Heights and launched the ill-fated invasion of Lebanon. Between 1984 and 1988, Israel was ruled by a Labour-Likud government with Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Shamir rotating as Prime Minister and Foreign Minister. This curious situation gave each party a power of veto over the more extreme policies of the other. Following the draw between the Likud and the Labour Party in the 1 November 1988 General Election, the two parties formed a national coalition government, with Shamir as Prime Minister: but Labour broke up the coalition in March 1990 because of irreconcilable differences over foreign policy. In June Shamir eventually succeeded in cobbling together a narrow coalition government, with the support of the religious parties and three small secular ultra-nationalist parties.

The key portfolios in the new government went to the members of Shamir’s Likud Party. David Levy, a populist of Moroccan origins, became Foreign Minister. Mr Levy does not speak English. But since little more than a dialogue of the deaf with the United States was likely on the peace process, this was not considered a severe handicap. Moshe Arens, an engineering professor of American origins whose reasonable manner masks unyielding nationalist convictions, moved from the Foreign Ministry to the Ministry of Defence. Ariel Sharon, chief architect of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, was back at the centre of government as Minister of Housing.

On the fringes of the government, but helping to set the tone, were two renowned hardliners representing tiny but highly vocal Arab-spurning parties with only two or three seats each in the 120-member Knesset. Professor Yuval Neeman of the Tehia or Renaissance Party was appointed Minister of Science, Technology and Energy, reinforcing his popular image as an Israeli Dr Strangelove. The agriculture portfolio was given to Rafael Eitan, the IDF Chief of Staff during the Lebanon War who once likened the Palestinians of the West Bank to drugged cockroaches. His party is called Tomet, which means ‘crossroads’ in Hebrew, though it advocates a straightforward policy of building Greater Israel. The Government as a whole is so fiercely nationalistic that Begin’s first government seems by comparison a model of tolerance and flexibility.

Mr Shamir himself appears to want to go down in history, not as the man who extended Begin’s peace with Egypt to Israel’s other neighbours, but as someone who stood firm and refused to yield any part of the ancestral land, Eretz Yisrael. Having abstained in the Knesset vote on the Camp David agreements, he maintains that the conditions that made possible the peace with Egypt do not obtain in relation to the Palestinians (‘the Arabs of the Land of Israel’, as he prefers to call them) or to any Arab state. He dislikes and distrusts the Arabs, and does not believe in the possibility of peaceful co-existence with them, at least not in the foreseeable future. Seeing the Arabs as primitive, volatile and blindly hostile to the State of Israel and its Jewish population, he questions the power of any diplomatic agreement to bring genuine peace and stability to the region. Personal experience of the Holocaust goes a long way to explain this deeply pessimistic outlook. Although Shamir rarely invokes the Holocaust, he is acutely conscious of his people’s vulnerability, and would expect the rest of the world to remain indifferent in the event of a real threat to Israel’s existence. For all these reasons, Shamir is an apostle not of peace but of self-reliance, of a consolidated Israeli presence on the West Bank, of a build-up in Israel’s military strength, and of steadfastness in relation to international pressures.

The Likud leader and his colleagues do not accept the basic formula of exchanging territory for peace on Israel’s eastern front. This formula lies at the heart of UN Resolution 242 of November 1967 and subsequent international initiatives to resolve the Arab-Israeli dispute, and is accepted, at least in principle, by the Israeli Labour Party. Historically, the Labour Party has been the proponent of ‘the Jordanian option’, of a settlement with King Hussein based on a territorial compromise over the West Bank, so as to deal with the Palestinian problem in a way that does not involve either negotiation with the PLO or the creation of an independent Palestinian state. Labour has also regarded, and continues to regard, the survival of the Hashemite monarchy in Jordan as essential to Israel’s security. Likud, by contrast, insists that Judea and Samaria, the official term for the West Bank, are an integral and inalienable part of the Land of Israel, and emphatically rejects any Jordanian claim to sovereignty over this area. Likud’s basic thesis is that Jordan is Palestine: that there is already a Palestinian state on the East Bank of the Jordan, since the Palestinians there constitute the majority of the population, and that there is therefore no need to create a Palestinian state on the West Bank of the Jordan.

A number of politicians inside the Likud such as Ariel Sharon, as well as in the parties further to the right, are also known to favour the large-scale expulsion of Palestinians from the West Bank to the East if a suitable opportunity presents itself. This implicit threat of Israeli ‘demographic aggression’ evokes in Jordan fears that verge on an obsession. It is one of the factors which induced King Hussein to sever the legal and administrative links between his kingdom and the West Bank in July 1988. Another significant consequence of this fear was to push Jordan closer to Iraq as the only Arab state capable of providing some sort of deterrent against a possible Israeli move to realise the thesis that Jordan is Palestine.

Another potential partner in the search for a settlement whom the Likud has helped to drive into the arms of Saddam Hussein is the PLO. The Likud’s rejection of the PLO has always been absolute. In other words, the Likud’s position is not that negotiations with the PLO would be possible if it met certain conditions, but that the PLO is a terrorist organisation with which Israel should refuse to negotiate under any circumstances. Scarcely less categorical is the Likud’s rejection of any Palestinian right to national self-determination in any part of Palestine. Here the difference between Likud and the Labour Party is much less profound than in relation to Jordan. This is why the Palestine National Council’s historic resolutions of 15 November 1988, renouncing terror, recognising Israel, and offering to partition Palestine between Jews and Arabs, failed to elicit any positive response from the Israeli side.

The PLO’s peace offensive, and the dialogue with the US Government for which it paved the way, cast Israel more clearly than ever before in the role of the obdurate party, and by harnessing their actions on the ground to the PLO’s moderate diplomacy, the local leaders of the intifada further helped to expose the intransigence at the heart of Israel’s position. As a result, a reversal of previous roles began to take place. In the aftermath of the June 1967 war it was the Arabs who were widely perceived as the intransigent party and Arab rejectionism was summed up in the three famous noes of the Khartoum summit: no to recognition, no to negotiation, no to peace with Israel. Now Israel was seen as the main obstacle to a settlement, and Israeli rejectionism was summed up by King Hussein as the Likud’s four noes: no to the exchange of land for peace, no to negotiations with the PLO, no to an independent Palestinian state, and no to an international conference to deal with the Arab-Israeli problem.

Once the PLO-American dialogue got under way in Tunis, Israel came under growing pressure from the Bush Administration to show some flexibility in order to re-activate the moribund Middle East peace process. American impatience with Israeli stonewalling was given an uncharacteristically blunt expression in a public statement by Secretary of State James Baker, vouchsafing the telephone number of the White House and telling the Israelis to call when they were serious about peace.

Something resembling a peace initiative was launched by the Israeli Government prior to Shamir’s visit to Washington in May 1989. The Government offered to hold free municipal elections on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and to allow the inhabitants a greater measure of autonomy in the running of their daily affairs. The offer was hedged around by restrictions. It did not extend the vote to the Arab inhabitants of Jerusalem. It promised no change in the political status of the territories. It stated that Israel would not conduct negotiations with the PLO, and that it opposed the establishment of ‘an additional Palestinian state in the Gaza District and in the area between Israel and Jordan’. Despite these obvious limitations, the Americans welcomed the initiative and wanted to pursue it vigorously. The Palestinians, however, rejected the offer, seeing it as a delaying tactic designed to propitiate American opinion and to take the sting out of the intifada.

There was thus complete deadlock on the Arab-Israeli peace front when Saddam Hussein surprised the world by invading Kuwait. The Iraqi invasion was greeted by Mr Shamir and his coalition colleagues with an inaudible sigh of relief because it shelved American plans to get Israelis and Palestinians round the negotiating table, and diverted international attention from the intifada. It also seemed to lend credibility to their contention that the principal threat to the stability of the region did not stem from the failure to solve the Palestinian problem, but from the ambition and greed of dictatorial Arab regimes of which Iraq was only the worst example.

The PLO leadership gave vent to the frustrations that had built up in the Palestinian camp over the previous two years by openly siding with the Iraqi tyrant, instead of standing by the inadmissibility of acquiring territory by force – a principle which would have served its cause better. The Israeli Government seized on this stand and the anti-Israeli rhetoric which accompanied it as further vindication of its refusal to have any truck with the PLO. Supporters of a dialogue with them on the Israeli left no longer had a leg to stand on. Some of them gave public expression to their disillusion with the Palestinians and closed ranks behind their own government. Yossi Sarid of the Citizens Rights Movement wrote in the independent daily Haaretz that if the Palestinians could support Saddam Hussein, who had executed tens of thousands of his domestic opponents and used poison gas against the Kurds, then perhaps it was not so terrible to support the policy towards the Palestinians of Yitshak Shamir, Ariel Sharon and Yitshak Rabin.

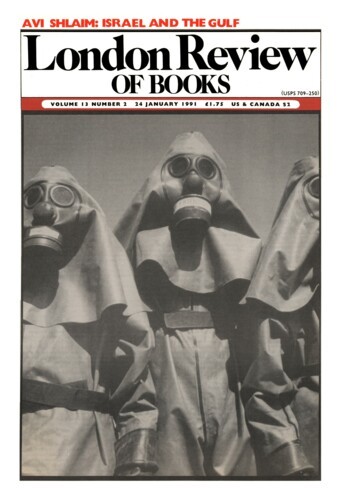

When Iraq invaded Kuwait, the Americans advised Israel to keep out of this particular quarrel, while themselves rushing forces to Saudi Arabia and assembling against Saddam Hussein a broad international coalition which included Egypt and Syria. The Americans wanted Israel to keep quiet, to stay in the background and not to complicate matters. The Israeli leaders were only too happy to oblige: the last thing they wanted to do was to help Saddam Hussein turn an Arab-Arab conflict into an Arab-Israeli one. So they kept a very low profile during the initial phase of the Gulf crisis. They even took the controversial decision to distribute gas masks to the civilian population in order to underline the defensive nature of their response. It was Saddam Hussein who first made the link between the Gulf crisis and the Arab-Israeli dispute by suggesting what he called ‘new arrangements’ between Iraq and Kuwait in return for an Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories. Both Israel and America firmly rejected any parallel between the two occupations and any linkage in dealing with them, and world opinion was largely on their side.

The turning-point came on 8 October when the Israeli security forces massively over-reacted to a riot in the Old City of Jerusalem and ended up by killing 19 Palestinians. Israel was back in the headlines. The massacre on Temple Mount provoked a wave of angry condemnation and redirected international attention to the plight of the Palestinians under Israeli rule. Israeli security forces had thus put an abrupt end to the Government’s policy of staying in the background. They had also appeared to confirm the link whose existence the Government had so strenuously denied and to underline the urgency of finding a solution to both problems.

The massacre strained Israeli-American relations, not least because of the damage it inflicted on America’s efforts to maintain the coalition against Saddam Hussein. Most Arabs regard Saddam’s occupation of Kuwait as not all that different from Israel’s occupation of Arab land, and accuse America of double standards in moving so energetically to put an end to the former after doing so little to end the latter. By joining in the universal outcry against Israel, the Bush Administration tried to limit the damage to itself. It even voted in favour of UN Security Council Resolution 681 of 21 December 1990, which condemned Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians in the occupied territories and supported a separate appeal for an international conference to settle the Arab-Israeli dispute. The call for a conference was non-binding and did not specify a date, yet it highlighted Israel’s growing isolation.

Another victim of the incident in Jerusalem was the policy of restraint in dealing with the intifada which had been inaugurated by Moshe Arens. Whereas his Labour precedessor Yitzhak Rabin had been responsible for the notorious policy of breaking bones, Arens instructed the security forces to remain as unobstrusive as possible in the occupied territories, to avoid unnecessary provocations and confrontations, and to keep to a minimum the use of armed force. As a result, the death toll was reduced almost to nothing, the intifada appeared to run out of steam and the media began to lose interest. The indiscriminate shooting of the 19 Palestinians dramatically reversed all these trends, and the intifada was transformed from a mass uprising against Israeli rule in the occupied territories into a low-intensity civil war between Arabs and Jews which no longer stopped at the pre-1967 border or green line, as it is called in Israel. On both sides of the line the extremists started coming to the fore and the upshot has been an escalation in the level of violence.

To check the wave of attacks on Israeli civilians and the pervasive insecurity caused by these attacks, the Army and Police barred Palestinians from coming into Israel. This was officially described as a temporary measure until calm was restored, but it nevertheless carries far-reaching implications. Over a hundred thousand Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza used to travel daily to work-places in Israel. One of the pillars of Israeli rule is the provision of employment to the inhabitants of the occupied territories. What the closure signifies is that Arabs and Jews cannot co-exist peacefully and the two must be separated by confining the Arabs to their areas. Paradoxically, it is a Likud government, ideologically committed to the unity of the land of Israel, which is now forced to revive the green line it has done so much to obliterate. The move was widely perceived in Israel as marking the beginning of a new era, and was welcomed as such by both Right and Left, though for rather different reasons. For the hard Right the move was a hopeful prelude to a more drastic policy, which some politicians openly advocate, of expelling the Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza to clear the area for Jewish settlement. On the left, the move was taken as the beginning of a separation between Israel and the occupied territories, and as further proof that the Likud’s Greater Israel programme is not viable.

The massive influx of Jews from the Soviet Union reinforces the trend towards separation between the Arab and Jewish communities and economies. More than a hundred and eighty thousand Soviet immigrants arrived in Israel in 1990. Between one and two million are expected to arrive by 1995. For the Jewish state, this mass immigration or aliya means fulfilment of the Zionist dream. But it also places a severe strain on government finances already stretched by the cost of maintaining a military alert in the face of the Gulf crisis. Soviet Jews are taking up some of the jobs Palestinian workers have been forced to relinquish, and this is bound to exacerbate the tension between the two communities. Mr Shamir’s repeated statements to the effect that large-scale immigration requires a large Israel do nothing to allay Arab fear of Israeli expansionism.

Ever since 2 August the threat from the East has overshadowed the Israeli Government’s preoccupation with domestic problems. As the crisis has unfolded, differences between Israel and America have come to the surface. The new tendency manifested in Washington to view the Gulf in terms of its own interests and the interests of Arab allies has fed Israeli anxieties that the influence of these allies over US strategy will grow, and given rise to complaints that the USA is being held captive by the anti-Iraq coalition it has formed.

Israel’s commitment to keeping a low profile has been based on the expectation that America would act to remove the Iraqi military threat. Any sign that America and her allies may settle for an Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait and a return to the status quo ante was therefore sure to deepen Israel’s concern. Bush’s offer to hold talks with Iraq was received in Jerusalem with dismay. David Levy declared that Israel would assume the highest possible profile should her security come under threat. His government informed Washington that it would feel free to deal with the Iraqi military threat if the United States and the international community did not. In the Israeli press this message was read as expressing a new policy in relation to the Gulf crisis. It certainly revealed some tension, not to say mistrust, between Israel and the United States and it seemed to reserve for Israel the right to take independent action to counter the Iraqi threat.

From Israel’s point of view, the best possible scenario for ending the Gulf crisis is an American military strike to destroy Saddam Hussein’s regime, his army and his military infrastructure, thereby erasing once and for all the threat from Baghdad, preferably without Israeli involvement. Although the Israeli Government has been careful to avoid giving the impression that it is egging America on to go to war, her influential friends there, like Henry Kissinger, have been publicly advocating this option since the first week of the crisis.

A second scenario which might be just about acceptable to Israel is to maintain the siege of Iraq and to keep the forces of the US and her allies in the region until someone in Iraq brings down the regime.

The worst scenario for Israel would be an Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait which would leave Saddam Hussein with his formidable military machine – army, long-range missiles, chemical and biological weapons and nuclear programme – intact. Such an outcome would permit him to continue to project his military and political power in the region, and it would erode Israel’s deterrent capability, which lies at the heart of her security doctrine. The long-term danger would be greatly magnified if Saddam emerged as the victor from the crisis by holding on to parts of Kuwait or by extracting concessions on the Palestinian issue.

Whether the crisis provoked by the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait is resolved by war or by containment or by compromise, one thing is certain: in the aftermath of the crisis Israel will come under the most intense international pressure for fresh ideas and for real movement to solve the Palestinian problem. There are signs that even the Bush Administration, while maintaining its refusal to discuss the two problems simultaneously on the grounds that to do so would reward Iraqi aggression, is beginning to bend to pressure to accept linkage between the Gulf crisis and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait has not altered the nature of the Palestinian problem in any fundamental way, but it has profoundly altered the international context. By posing the first major challenge to the post-Cold War international order, the Iraqi dictator has inadvertently helped to forge a remarkable concert of powers that includes the United States, Western Europe, the Soviet Union and some of the most powerful Arab states. All these powers are now committed, in varying degrees, to promoting a negotiated settlement to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict once the immediate challenge from Iraq has been dealt with. They are unlikely to tolerate an attempt by Israel to return to the ‘do nothing’ policies of recent years. A growing number of Israelis have also come to recognise that time is not on their side, that there is no military solution to the intifada, and that bold political initiatives are needed to arrest the slide towards civil war. Yitzhak Shamir, the 75-year-old master of the art of stonewalling, is not of that number.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.