More than any other capital city, Jerusalem demonstrates the power of symbols in international politics. The conflict between Israel and the Palestinians is one of the most bitter and protracted of modern times, and the Jerusalem question, a compound of religious zealotry and secular jingoism, lies at its heart. The Oslo Accords, which launched the Palestinians on the road to self-government, bypassed the matter of Jerusalem along with the other truly difficult issues in the dispute: the right of return of the 1948 refugees, the future of the Jewish settlements in the Occupied Territories and the borders of the Palestinian entity. Discussion of these was deferred until negotiations took place on the final status of the territories, due to begin towards the end of a five-year transition period. They were belatedly tabled at the summit convened by Bill Clinton at Camp David in July 2000, but Jerusalem was the issue that ultimately led to the failure of the summit and the breakdown of the Oslo peace process.

Religious rivalries are notoriously difficult to resolve, and Jerusalem’s spiritual significance for the three great monotheistic religions has ensured its long and bloody history. And then there is the political prestige that has always gone with possession of the city. Between its foundation and its capture by the Israelis in 1967, it is said to have been taken 37 times, and it has now been on the international diplomatic agenda for a century and a half. When Arthur Koestler visited it during the 1948 war, he was filled with gloom at the ‘international quarrelling, haggling and mediation’ that he could see looming. ‘No other town,’ he wrote, ‘has caused such continuous waves of killing, rape and unholy misery over the centuries as this Holy City.’

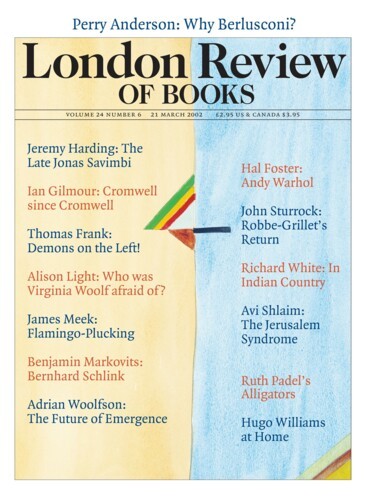

Anyone seeking to understand the Jerusalem question in its current form could not do better than read Bernard Wasserstein’s thoroughly researched, elegantly written and strikingly fair-minded book. Its starting-point is what psychologists have long been aware of as the ‘Jerusalem syndrome’ that afflicts some visitors to the city, especially Western Christian tourists, who feel a need to register their presence in the Holy City by assuming the identity of a Biblical character, undergoing mystical experiences or succumbing to the delusion of possessing supernatural powers. Jerusalem, in other words, represents not just a problem but also an emotion: above all, a religious emotion. Veneration for the city among Jews, Christians and Muslims runs deep and it is the duty of the historian, as Wasserstein sees it, to record this fervour without succumbing to it. From here, he goes on to develop his argument that politicians of all three religious affiliations have deliberately inflated the city’s religious importance to serve their own political ends.

When the Ottoman Turks captured Jerusalem in 1516 it was a provincial backwater with a population of fewer than 15,000. It didn’t acquire any administrative importance over the four centuries of Ottoman rule, but served only as the capital of a district forming part of the province of Damascus. During the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent it acquired the walls enclosing the city that are still almost intact today. But the various religious groups were left to run their own affairs and to administer their own institutions, with little interference from the central government. The Jerusalem question in its modern form arose as a by-product of the slow decline of the Empire. The initial struggle was over the Christian holy places. As Ottoman power waned, the other great powers sought to extend their authority and prestige, and Wasserstein lays bare the methods they employed with a wry humour in a chapter on ‘The Wars of the Consuls’: religious sentiment was exploited, local protégés were cultivated, dependent institutions such as churches, monasteries, convents, hospitals, orphanages, schools and colleges were founded.

Wasserstein also gives credit where it is due. He notes that in the late Ottoman period, there were no significant instances of mass communal violence in Jerusalem. Relations between Muslims, Christians and Jews, while often fraught and acrimonious, were contained within a framework of law. What the consular wars illustrate rather is the propensity of the Jerusalem question to inflame relations between the powers: ‘Seized upon as a sacred cause, Jerusalem proved a handy pretext for warmongers with much larger objectives.’ This isn’t something that has faded with the passage of time.

Britain governed Jerusalem, under the Palestinian Mandate, from 1920 until 1948. Nominally, it was responsible to the Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations but in reality Palestine was governed as if it were a Crown colony. Although British rule lasted only three decades, it transformed the city and paved the way to its eventual partition. This was Jerusalem’s first Christian administration since the Crusades, yet it granted unprecedented privileges to the Supreme Muslim Council and sponsored the establishment of a Jewish National Home. Breaking with the Ottoman past, the city became a major administrative centre and the seat of the High Commissioner for Palestine. The result was a profound change in its relationship to Palestine. For the first time in its modern history, Jerusalem was a capital. The status of the local elites, Muslim as much as Jewish, was enhanced by their proximity to the seat of power. The British tried to be even-handed, but reconciling the claims of the two nascent national movements proved beyond them. Both Arabs and Jews became progressively alienated and staged revolts against British rule, the former in the late 1930s, the latter in the late 1940s. By the time the Mandate reached its inglorious end in May 1948, there was precious little goodwill left towards Britain on either side of the divide.

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations passed a resolution for partitioning Palestine into two independent states, one Arab and one Jewish, but with an international regime for Jerusalem, which was to be treated as a corpus separatum. Formally the British remained neutral, but in practice they were hostile to the plan for an independent Palestinian state because it was certain to be ruled by the Mufti, Hajj Amin al-Husseini, who had thrown in his lot with Nazi Germany during the Second World War: their secret objective was partition between the Zionists and King Abdullah of Jordan, their loyal ally – which was the precise outcome of the 1948 war. Towards the end of that war, Jerusalem once again became an issue. Most members of the UN still supported an international regime for the city but the powers on the ground, Jordan and Israel, were united in their wish to partition it between themselves. After the guns fell silent, Jordan continued to rule East Jerusalem and Israel to rule West Jerusalem, until the six days that shook the Middle East in the summer of 1967.

By joining Nasser in that war, King Hussein lost the West Bank and East Jerusalem, which his grandfather had incorporated into the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan by the Act of Union of 1950. Jordan’s participation in 1967 was largely symbolic but the price it paid was heavy. On 7 June, Israeli forces captured East Jerusalem as part of their sweep through the West Bank. At noon that day, Moshe Dayan, the defence minister, went to the Western Wall and declared that Jerusalem had been ‘liberated’: ‘We have united Jerusalem, the divided capital of Israel. We have returned to the holiest of our Holy Places, never to part from it again.’ Contrary to the view held by most Arabs, Israel had no prior plan for keeping the West Bank or East Jerusalem, but the victory unleashed powerful currents of religious messianism and secular irredentism that no government could have held in check even if it had wanted to. The Zionist movement’s moderate position disappeared overnight, and suddenly life in the Jewish state without Zion (one of the Biblical names for Jerusalem) became difficult to imagine. At the end of June, in a remarkable display of unity, the Knesset enacted legislation to extend Israeli jurisdiction and administration to Greater Jerusalem, which included the Old City (the small area inside the walls which is divided into four quarters – Jewish, Christian, Muslim and Armenian). This was annexation in all but name.

Over the next quarter of a century, the central political figure in Israeli Jerusalem was its mayor, Teddy Kollek. A liberal-minded and pragmatic man, he sought practical solutions to the city’s many everyday problems and was anxious to achieve harmony among its different groups. But his overriding aim, which he made little effort to conceal, was to secure Israel’s permanent hold on Jerusalem as its unified capital. The expropriation of Arab land in East Jerusalem proceeded at a rapid pace and new Jewish neighbourhoods were built in flagrant violation of international law. Driving all this hectic activity was a long-term geopolitical aim: the creation of a ring of Jewish settlements on the northern, north-eastern and southern periphery of the city. As Kollek himself admitted in a newspaper interview in 1968, ‘the object is to ensure that all of Jerusalem remains for ever a part of Israel. If this city is to be our capital, then we have to make it an integral part of our country and we need Jewish inhabitants to do that.’

The position of the great powers remained virtually unchanged: they refused to recognise the legality or legitimacy of the Israeli attempt to incorporate East Jerusalem. The United Nations passed a series of resolutions condemning Israeli activities in the Arab quarters. But external pressure failed to dent Israel’s confidence in its moral right to impose its rule over a large and recalcitrant Arab population. On the contrary, in nationalist circles at least, it provoked deep resentment and defiance. In July 1980, the Knesset passed the Jerusalem Law, which stated that ‘Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel.’ Its initiator, the ultra-nationalist Geula Cohen, made it clear that her purpose was to foreclose any negotiations over the status of the city. Unlike earlier legislation, the Bill was widely criticised within Israel as unnecessary, even harmful. It set Israel on the defensive internationally and drew criticism from all the major powers. On 20 August, the Security Council passed a resolution reprimanding Israel by 14 votes to zero, with the US abstaining. The New York Times called the law ‘capital folly’.

In the years since this capital folly was enacted, Israeli leaders of all political shades have continued to repeat the mantra that unified Jerusalem is the eternal capital of the State of Israel, and its status non-negotiable. It was to get round this self-imposed constraint that the Israeli participants in the Oslo Accords set the Jerusalem question aside. The Declaration of Principles signed on 13 September 1993 had little to say about it. The Palestinian Interim Self-Government Authority was to have no jurisdiction over Jerusalem, and the status quo was to continue until the ‘final status’ negotiations. In the meantime, both sides were free to cling to their symbols of sovereignty and their dreams. An optimistic Yasir Arafat said that the agreement was merely the first step towards ‘the total withdrawal from our land, our holy sites, and our holy Jerusalem’, while an Israeli spokesman insisted: ‘Jerusalem is not part of the deal and there has been no weakening on that.’

The framework for a final status agreement was concluded on 31 October 1995 by Yossi Beilin, Israel’s deputy foreign minister, and Mahmoud Abbas (better known by his nom de guerre Abu Mazen), a close adviser to Arafat. This bold document made a first stab at resolving all the outstanding issues between Israel and the Palestinians. It envisaged an independent but demilitarised Palestinian state, covering Gaza and 94 per cent of the West Bank, with al-Quds (East Jerusalem) as its capital. Four days later, Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated and his successor, Shimon Peres, lacked the courage to adopt the plan, not least because it would have exposed him to the charge of dividing Jerusalem. In the elections of May 1996 Peres was narrowly defeated by Binyamin Netanyahu, the leader of the right-wing Likud. On coming to power, Netanyahu abruptly reversed the cautious peace policy of his Labour predecessors, especially with regard to Jerusalem. Oslo was meant to hold Jerusalem back till the end of the process: Netanyahu placed it at the centre of his policy, thereby blocking progress on all the other issues.

The question did not make another significant appearance on the international agenda until the Camp David summit which Clinton convened at the request of Netanyahu’s successor, Ehud Barak. At Camp David, Barak and Arafat negotiated more back to back than face to face. Both had serious internal problems. Barak’s coalition was crumbling and he arrived at the conference as the head of a government on the verge of collapse. Arafat was under pressure not to yield on the Palestinian demand for an Israeli withdrawal from the whole of Arab East Jerusalem. The city was the core issue at the summit and the main stumbling block. To break the deadlock, the American mediators put forward ‘bridging proposals’ broadly based on the Beilin-Abu Mazen plan. But there was no meeting of minds between the two delegations and no real negotiations took place. Arafat stood his ground, failed to put forward any constructive counter-proposals, and refused to give way on Jerusalem and the holy places. Clinton’s suggestion that the issue be postponed for later determination was also rejected by Arafat, and a frustrated Clinton likened the whole experience to ‘going to the dentist without having your gums deadened’.

After the breakdown of the talks, another round of violence was inevitable. On 28 September 2000, Ariel Sharon, the leader of the opposition, sparked it off by his ostentatious visit to Temple Mount. Surrounded by a phalanx of security men, he claimed he was going to deliver what he called ‘a message of peace’. To the other side, the message that came across loud and clear was ‘Israel rules OK!’ The visit sparked off riots which spread from Temple Mount to the Arab quarters of Jerusalem, the West Bank, Gaza, and for the first time, some of the Arab-inhabited regions of Israel. Riots quickly turned into a full-scale uprising. Within ten days, the death toll of what became known as the al-Aqsa intifada was approaching 100. The Oslo Accords were lost to view in the outpourings of collective hatred that accompanied the return to violence.

Against this grim background Clinton made one last attempt, just before the end of his term, to bridge the gap between the sides. At a meeting at the White House with Israeli and Palestinian representatives in late December, he presented his ideas for a final settlement. These ‘parameters’, as he called them, had moved a long way towards meeting Palestinian aspirations. Israel was to withdraw altogether from Gaza and from 94-96 per cent of the West Bank. There was to be an independent Palestinian state but with limitations on its level of armaments. The guiding principle for solving the refugee problem was that the new state would be ‘the focal point for the Palestinians who choose to return to the area’. With regard to Jerusalem, ‘the general principle is that Arab areas are Palestinian and Jewish ones are Israeli.’

Negotiations on the basis of the parameters took place at the Egyptian Red Sea resort of Taba in the last week of January 2001. Both sides broadly accepted the proposals but with a long list of reservations. On Jerusalem, Israeli reservations were more substantial than those of the Palestinians. Barak stated publicly that he would not transfer sovereignty over Temple Mount. At this critical juncture, as so often in the past, internal Israeli politics took precedence over everything else. The elections scheduled for 6 February led Barak to adopt a tough line over the Old City and Temple Mount. Despite these local difficulties, however, the negotiators came closer to a final agreement than they ever had. But then Sharon won the election, and his Government immediately declared that the understandings reached at Taba were not binding because they had not been embodied in a signed document. To make things worse, the incoming Bush Administration didn’t consider itself bound by the proposals of its predecessor and in any case chose to disengage from the peace process. Most of the achievements of the Taba talks disappeared into the desert sand.

In the preface to this admirable book, Wasserstein observes that the ‘eternally unified capital’ of the State of Israel is the most deeply divided capital city in the world: ‘Its Arab and Jewish residents inhabit different districts, speak different languages, attend different schools, read different newspapers, watch different television programmes, observe different holy days, follow different football teams – live, in almost every significant respect, different lives.’ What the book eloquently demonstrates is that the struggle for Jerusalem cannot be resolved without some recognition of the reality and legitimacy of its plural character. It is sad to have to add that such recognition is a more remote prospect today than at any time since the Oslo Accords were signed.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.