Sidney Nolan was born in Melbourne in 1916. His father was on the trams, but did rather better at illegal bookmaking. They were Irish, working-class, lapsed Catholics. Sidney left school at 14 and spent his late teens in irregular employment and part-time art education. He could not draw well enough for Mr Leyshon-White’s commercial art agency, so he ran the correspondence course. He enjoyed writing to rural amateurs telling them how bad their work was. Later he made advertising displays and did a little modelling for a hat company. He read a great deal, and made illustrations for Joyce’s Ulysses, which was banned and could only be read at the National Library. He lived for a while in a ‘weekender’ (a cottage in the bush) and tried to stow away on a ship to Britain. By the time he was 21 he had worked as cook in a hamburger bar, helped lead a strike in the hat factory, and married.

He wanted to get to Europe, but he was not a competent enough draughtsman to win a scholarship. Sir Keith Murdoch, the newspaper proprietor, offered bursaries, but his advisers also wanted evidence of skill. One of them, however, suggested he see John Reed. Reed was a solicitor, interested in Modernism. He lived with his wife Sunday in a house called Heide, in Heidelberg, a semi-rural community outside Melbourne – it had given its name to the Heidelberg School of Australian painters in the late 19th century. Their circle was bohemian and promiscuous. Nolan’s wife resented his connection with the Reeds and divorced him. The war came and Nolan found congenial billets guarding stores depots on the flat wheat-growing plains of the Wimmera. Here he began painting landscapes. He evaded promotion, and when it appeared that he might be sent to fight in New Guinea pleaded physical sickness and mental troubles. The medical officers did not believe him, and he deserted and finished the war living with the Reeds at Heide. There, in the mid-Forties, he painted a sequence of pictures of the life and death of the Australian outlaw Ned Kelly which were to be his most famous work.

The magazine Angry Penguins which had been started in Adelaide by Max Harris was now run jointly with John Reed, and one of Nolan’s paintings was reproduced on the cover of the notorious ‘Ern Malley’ issue. Ern Malley was a poet invented by two young men who thought Modernism had destroyed the craft of verse. They compiled his poems by picking fragments at random from the Concise Oxford Dictionary, Shakespeare and a dictionary of quotations. For many Australians, this hoax confirmed that Modernism was a fraud. Others believed that anyone might be taken in by minced Shakespeare, and that fakers can be tripped into creativity.

The emotional strain of the ménage à trois he was living in with the Reeds became intolerable, and Nolan went north to another exotic landscape, Queensland. On his return he looked up John Reed’s sister, Cynthia. He married her in 1948.

His reputation began to flourish. Kenneth Clark was struck by one of his paintings in a group exhibition and suggested he would do well in England. It was good advice, and Nolan became an established artist in Europe. His working life became a series of journeys, sometimes back to Australia, but also to Antarctica, Africa and America, which were often the occasion of new sequences of paintings. He became a popular provider of book jackets (C.P Snow and Patrick White, for example), and of stage sets for ballet and opera. The Queen bought his pictures, and he was knighted and awarded the OM. Kenneth Clark wrote an introduction to a monograph on Nolan’s work, and Nolan went to Sweden to accept Patrick White’s Nobel Prize. His private life was difficult. His wife committed suicide in 1976, and as most of their property was in her name, and left to her daughter, he was, for a while, financially embarrassed. In his autobiography Patrick White criticised Nolan for remarrying so soon after Cynthia’s death, and Nolan answered with as insulting a painting of White as he could manage. His relationships with patrons in Australia have sometimes been difficult. Gift horses have been looked in the mouth, large works have not always found prominent sites. He now lives in England, in a manor house called The Rodd.

The great achievement of Nolan’s early years as a painter was to find a way of evoking the strangeness of Australian landscape, and to see that landscapes painted in that mode could be peopled with characters and buildings, painted in a primitive style, which could carry a story. The disjunction, far from destroying the effect of either part, gave a better account of the oddness of Victorian Europe in primeval Australia than correct tonal or Impressionist transcriptions of things seen had done.

As Nolan’s work developed, this contrast disappeared: the smeared paint – perhaps it looked like that because he was painting on board – is used for the figures and animals as well as the landscapes. In the eyes of many critics his work lost its force; to take on Africa and Antarctica in the same spirit as he had taken on Queensland or New South Wales contradicted the notion that his genius was peculiarly Australian. When he drew Leda and the Swan as well as Burke and Wills, neither of the niches prepared for him – the Great Australian Painter and the Honest Colonial Eye – seemed to fit. It was as though L. S. Lowry had started to paint Pittsburg. Nolan’s early Australian landscapes found some sympathetic local critics: there is also anecdotal evidence that Australians who had no special interest in art found them true to the country. He might, like Lowry, have become a famous and well-liked provincial painter. The particularity of his vision was lost in the larger themes and grander schemes of his European phase.

Brian Adams’s biography is clumsily written. He trips over himself grievously when he tries to explain things frankly as well as painlessly. He sums up the relationship with the Reeds, which emerges in the book as the most important formative influence on Nolan, as though he was reporting on a group encounter session: ‘The French would describe the relationship as a ménage à trois, although it was much less formal, having a freedom where all kinds of permissiveness were accepted as part of the total physical and intellectual experience.’

Nolan has made a career in the mainstream of Modernism. The byway into Lowry-like provincialism was not taken. He started off admiring Picasso and Miro, he has become an international painter with Australian roots. Andrew Wyeth took the opposite course. He was taught by his father, N.C. Wyeth, a successful illustrator, who had been taught by another, Howard Pyle. His paintings look like magazine illustrations. His subject-matter is limited to people, buildings and landscapes to be found close to the family house in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. The compositions are sparse, and often uneasily balanced. His paintings and Robert Frost’s poetry describe similar landscapes and characters. Frost has been better respected by critics, but Wyeth has advocates among the directors of famous American public galleries, and their patrons.

The Helga Pictures is the catalogue of the exhibition of 240 paintings and drawings made of one neighbour, Helga Testorf, between 1971, when she was 38, and 1985. In an introduction Leonard Andrews, who owns the collection, writes: ‘It was clear that one of Andy’s main interests was that it should be shown to the public in a respectful and dignified manner.’ This is a reflection of the ‘intense and massive press coverage’ which followed the announcement of the acquisition of the pictures by Andrews in 1986. At the time it was said that Wyeth’s wife had been unaware of their existence. Mr Andrews says he asked no questions about Wyeth’s relationship with his model, considering it to be ‘a professional one of their own making’. John Wilmerding’s introduction ponders the ‘intellectual and artistic productivity of men in late adulthood’ – and the avoidance of the term ‘old man’ seems planned to keep ‘dirty’ out of the reader’s mind. For a number of reasons the pictures do seem voyeuristic and fetishistic. The nudes are shown in what look to be small, bare, cold rooms, into which light comes from curtain-less windows, cracks between closed shutters or nearly closed doors. The careful delineation of head and body hair seems obsessive. The fact that the model is often observed sleeping emphasises her vulnerability.

The atmosphere is awkward, and the pictures are memorable because of it. The drawing is often feeble, but there are compositions which (like some scenes in movies) suggest that an event of some significance has taken or will take place. They are, in this sense, literary. Hilton Kramer’s remark that they are ‘just’ illustrations, nothing to do with ‘serious artistic expression’, prejudges the matter of illustration; and his belief that the reason people ‘go gaga’ over Wyeth’s paintings ‘is that they offer a picture of a nostalgic bucolic sentimental past that never existed’ is less than fair to the popular imagination.

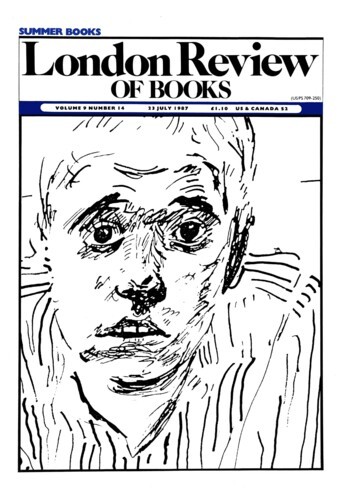

David Hockney’s career has been a pleasure to watch. His subject-matter – places he has visited or lived in and people he had known – has been interesting and decorative. Through representations of these agreeable subjects he has explored ways of picturing the world. His native talent as a draughtsman, and the use he has made of such toys as the Polaroid camera, have given this entirely serious enterprise the lightheartedness of a string of variety acts. His latest mechanical aid is the copying machine. Faces is the catalogue of an exhibition of portrait drawings made during the last two decades. Rather than reproduce the drawings in their entirety from photographs, Hockney has made photocopies of details. The strengthened, simplified, cruder, stronger images thus produced are presented as original interpretations. The impact of the images as you turn the pages is tremendous. The changes made to the original images by the copying process is rather like the change made to drawings by Bonnard or Lautrec when the artists drew directly on lithographic stones.

These three books give different glosses on the question of genius. ‘The fact is,’ Kenneth Clark told an audience in Dublin, ‘that Sidney Nolan is a genius and a genius cannot do what he wants, still less what his admirers want him to do. He is under orders – Genius comes from somewhere else.’ One imagines the genius as a large sea creature, obeying a migratory urge. But, to extend the metaphor, the genius is buoyed up on tides of appreciation. When they recede, the great whales of art are left on the beach, crushed by their own unsupported weight. It is possible to feel that Nolan is already in shallow water. Tides in the bay where Wyeth swims rise and fall slowly: his reputation will see him out. Hockney, more of a porpoise, is unlikely to be stranded.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.