I don’t expect to forget Edgar Reitz’s 11-part film Heimat, which ran like a river on BBC 2 in the early summer, and which tells the story of a family, and of a community, in the Hunsrück region of Germany over the years 1919 to 1982 – a long film for a long haul. Towards the end of that interval of time Reitz’s work became an object of hostility for the exhibitors of the German film industry: I gathered as much from an interesting Observer Profile, which also explained that, in making Heimat, this highbrow chose to ‘stick to hard facts’ and to ‘curb his “intellectuality” ’, directing it into a notebook, and which claimed that the film had restored a sense of the national past in delivering a tension between traditional ways and a ‘thrust for individual identity’ in the technological modern world. The Profile may have enlivened what I took to be a rather anaemic response to the film since it was first shown in cinemas in this country. My impression is that cinéastes shrank from it as from some sort of solid up-market soap opera, and that in being seen as unduly popular, it has failed to flourish. So much the worse, if so, for British audiences. Heimat strikes me as one of the most important events in the history of the cinema.

Much of its authenticity may derive from the fortunate, if not unflawed relationship – which could be called a further tension – between the author’s autobiography and ‘intellectuality’ and his concern for fact, the facts of the Hunsrück, whereby every last little thing, including the setting of an alarm clock, is made worth watching. Heimat has in it the departure of a young husband, the isolation of his grass widow, and then the departure of her son by another man. In the second departure – which is linked to a love affair of the son’s and to his espousal of the advanced art of electronic music – Reitz’s own experiences in the world are embodied. In the first departure, the father’s, which is completed by his return in the shape of an elderly and grisly German American, we may find, on the thrust, an individualism comparable to the son’s. Both departures are specific to the period in question, but they are also an ancient thing and a fairy-tale element, picturing the magical stranger, the outcast’s reward – which is equally, here, a punishment. In and around and over and under this are the coming and goings of the Hunsrück. The film is true to the life I remember from National Service after the war, to the Germany which had yielded to Hitler but which went on to take command of its defeat. It brought back the wrinkled tawny moon-faced old man who wanted to tell an enemy soldier on a train about the glocken he’d spent his life making, and would go making for as long as he could. The film records the rise of a mentality which would have sold that old man’s bells for scrap or hawked them as antiques: but it also has in it the spirit which enabled the country to keep going – a spirit not confined to the business community.

I daresay, though, that one shouldn’t ascribe too much in the way of patriotism to the film, which in none of its 11 parts is ever monumental, triumphal or sentimental, which presses no judgments but which judiciously qualifies its accounts of the place and the persons who have inhabited it. The principal acts of cruelty and coldness – some of which come from the mother, Maria, in her isolation, and from her controlling mother-in-law – are those of people who are not ogres. The human failings of the Old Hunsrück are admitted; the new technology and its exploiters are not shown as monstrous. In keeping with this, there is uncertainty in the account that is given of the son’s avant-gardism. Having gone for a prevailing, historically appropriate black-and-white, Reitz himself is avant-garde enough to fleck the film with colour as a heightening for critical moments. In the context of the film at large, however, these dabs and flecks could be thought an alien feature – caviare to the general, Stockhausen to the Hunsrück. And Heimat is certainly not sufficient of an avant-garde work to forbid one to listen with the ears of the country people when outlandish sounds penetrate their seclusion. It even allows a suspicion of satire to attend the human occasions which surround the technology-intensive new music. At the same time, one suspects that Reitz is probably more patriotic about that than he is about the new Germany.

Reitz’s subtlety and truth is the kind of thing that is rarely available to the television authorities, who are in any case supposed to offer all sorts of shows, few of which are intended to invite comparison with Heimat. Not that they do offer all sorts: many of their shows project more or less indistinguishable fantasies of violent crime, and many of them represent a narrow range of formula material bought in from America. But they are supposed to, and no viewer would expect Heimat to set a standard, however much it may have made his summer. If we were to turn to the British film industry in search of comparisons, the search would prove more difficult. Television went ahead with a roar in Britain, and, amid cries of protest from Westminster politicians, became the best in the world. Meanwhile the film industry wilted, and abandoned the effort, such as it had ever been, to contribute to the life of the country – a matter on which politicians were silent. Practically nothing of any importance that has happened to people here since the war has been seen on their cinema screens. Television did much to fill that gap, but it is now doing less. In particular, the excellence of the BBC has broken down. The former BBC executive John Gau has alleged, in these columns, a monopolistic, dinosauric gigantism. And as Gau conveyed, this tendency is linked to a reluctance to risk the unpopular and the unusual (as distinct from the routinely scandalous and untoward) in giving opportunities to film-makers with something of their own to say.

In the past few months the BBC has had to negotiate several sticky passages in the corridors of power. It may have been spared a report from the Peacock Committee which fully satisfied Mrs Thatcher’s desire to subject the Corporation to advertising, but the report appears to have been succeeded by plans for the commercialising of Radios 1 and 2. With the death of the Chairman of its Board of Governors, Stuart Young, we have been braced for another of the disobliging appointments to this post whereby governments have tried to subdue the Corporation. Mrs Thatcher’s man was said to have been Lord King, privatiser of British Airways, and a highly unsuitable choice that would have been. We have been spared Lord King, who has withdrawn, and rumour has had it that we may be given Lord Barnett instead, someone with no burning interest in broadcasting but with an excellent ministerial record. Rumour, though, has also produced the sense that some dark horse from the fair fields of business may be waiting in the wings.

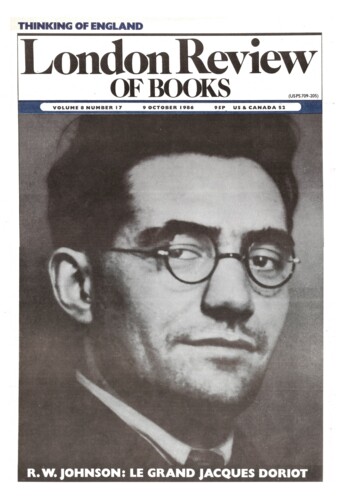

Stuart Young’s dependability as a government appointee was tested by the row over the Real Lives documentary on Northern Ireland, which divided Governors and Management. The programme attempted to strike a balance, of the kind traditionally associated with broadcasting – by matching the portraits of two paramilitary schemers, antagonists who resemble one another: the devout Martin McGuinness of Sinn Fein/IRA and the devout Peter Robinson, a Loyalist leader who has gained in clout since the programme. There will be those who think that the new Robinson is partly due to the fact that, in the programme that was eventually transmitted, the public was allowed to listen to Robinson’s sanitised version of what he would like to do about the IRA. The Government saw the proposed programme at the time as conducive to civil disorder, and the Governors in effect agreed. This sticky passage portrayed the BBC as subject to a level of government pressure unprecedented since the war – which was R.W. Johnson’s charge on the Letters page of this journal, two issues ago.

Those on the outside may be entitled to feel that tensions between government and the media are inevitable and often salutary, and that at a time of war, or terror, a democratic government, like any other, is bound to interfere. At any time, however, governments tend to interfere in order to secure political advantage, and at the end of that line stands the end of democracy, and of believable broadcasting. The Governors should have been a lot less willing than they seem to have been to take the not especially reliable Leon Brittan’s word for it that extremists should not be heard on television. They might have reflected that the troubles will not go away if the public is kept in ignorance of what the gangsters in the community are on about, that Protestant extremism has in fact been a familiar voice on television, but that television has nevertheless achieved a far from inflammatory Ulster coverage – far from inflammatory and far more informative than what has been forthcoming from the press.

Another painful development was the publication in June of Michael Leapman’s Last Days of the Beeb: a narrative of power plays and mean-spirited intrigues. Here was a writer about the BBC for whom the programmes and their producers did not seem to matter all that much. What mattered was behind the screen, and at the top, and it proved a sordid sight. There is more to the BBC than the story – and others like it – of how Aubrey Singer received his quietus after a day of red wine and blood sports in the dear old English countryside, and after a life of service to broadcasting. What more there is, though, has not been communicated in the statements we have become accustomed to receive from its spokesmen, who do not seem to be very interested in the programmes either. If Mr Leapman is right about the editorial outlook of his top persons, then the justification of public-service broadcasting which is now imperative will have to be left to others.

When politicians interfere with the BBC, balance is enjoined. And the BBC has enjoined balance on itself, though in a somewhat different sense. By many of those who are not politicians it has long been accepted, I think, that the criterion should apply to the range of programmes, and not to every single one. And you have to be a Member of Parliament, or an interested party, to doubt that a good programme is apt to be unbalanced, apt to express an opinion and to exhibit an author. Broad as its sympathies were, and self-effacing as Reitz may have wished to be, Heimat was not a balanced programme, and Margaret Thatcher would have found it unfair to entrepreneurs. Noel Annan has been saying in strong terms that the BBC has a duty to be ‘dispassionate’ about affairs of state, and that it owes this duty to the state, rather than the government: a distinction which has come to the fore lately, but which is not easy to grasp. He was aware of ‘violent and unsuitable programmes’ broadcast at the time of the Falklands war and critical of that war. I was not aware of such programmes myself: but I was aware that many people disputed the use of violence at that stage in the development of this particular affair of state, and many people since then, including a former prime minister, have come to judge the Falklands war as unnecessary or worse. Would it have been a better BBC that blacked such opinions out? Do the holders of such opinions not belong to the state to which the BBC owes a duty? No one was dispassionate about the Falklands conflict, and for the BBC to have refused to acknowledge the existence of a passionate (or indeed of a rational) dissent would have spread the view that it is an instrument of government propaganda. It is true that this dissent had no political party to turn to for expression. And it is also true that the BBC appeared to want to atone for whatever lapses it might have committed: victory was celebrated in a manner that made the relief of Mafeking look like a setback.

This is not an argument which denies or abridges the right to complain about distortion or inaccuracy, as in the case of that unlikely-looking programme which recalls the military maltreatment of British soldiers during the First World War, The Monocled Mutineer. These are battles which are often misconceived but which will always have to be fought. But it is not clear to me why a programme which falls outside the category of News should be more open to objection than a book or a play, and exposed to all this confusing talk of balance, and of freedom from feeling. I remember protests over Joan Littlewood’s very fine theatrical derision of Great War brass hats, Oh, What a Lovely War: but it would have been implausible to have spoken of punishments and a ban.

Broadcasting should be allowed to go on being both balanced and unbalanced, while public-service broadcasting should be both popular and unpopular. This could be a way of scaling down the BBC, and it could be a basis for the defence of the BBC which is now needed, with a government engaged on a wrecking of national institutions which calls itself a cure. A smaller BBC, and one which settled for a smaller share of the mass audience, need not be less valuable than the one we have now, or more vulnerable to political pressure. Perhaps we should tell ourselves that even if the British Broadcasting Corporation were to go the way of British Airways, the old project of public-service broadcasting might nevertheless survive. There are those who feel that the project has been re-animated by the success of ITV’s Channel 4, which has been doing the BBC’s job for it, they claim. This success may be held against the Corporation as the day of reckoning approaches: but it could also be used to assist its retrenchment.

Something is always being held against the BBC, but both sides of broadcasting were party to a strange situation which seemed to have arisen in the field of sport. The football season had begun, but the national game was for weeks barely detectable on the screen. Instead, there was American football, and Irish football. A recognisably British situation, we might think by now, strange as it is. I have been assured that the reason is that the Football League had disliked the broadcasters’ (enlightened) proposal of an arrangement based on the weekly transmission of live matches in their entirety, rather than highlights. But for a moment there I thought the Government had intervened, in order to cause pain to soccer hooligans – who watch, as it happens, neither soccer nor television.

The BBC 2 Dimbleby Lectures have not been remarkable, I’m glad to say, for balance. This summer’s lecture argued for a more affirmative view of commerce and technology, and did so eloquently and reasonably. The tone was not that of a recent Times leader on the deplorable ‘deep connection between British attitudes towards technology and towards money-making. The country needs more of both.’ The speaker was the head of ICI, John Harvey-Jones, who has his place, so far as I’m concerned, in the history of postwar Germany. He was a Naval Officer with the occupying forces not long after the war, and his wife was a star of the voluminous drama productions put out by the British Forces Network in Hamburg. The message of the lecture jarred a little with that of Heimat: but both occasions brought memories of these two admirable and delightful people – good company, I thought, for that bell-maker of mine, with his Medieval technology. I listened carefully to the evocation of a business community which has still to reach the status of occupying force, just as I listened carefully, five minutes after finishing this diary, to a rumour that the dark horse who was to become Chairman of the BBC was John Harvey-Jones.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.